A newly identified lung cell “switch” could help doctors unlock the lungs’ natural ability to heal themselves.

Dr. Ryan Cloutier: “We’ve seen this pattern: rocky inside, gaseous outside, across hundreds of planetary systems. But now, the discovery of a rocky planet in the outer part of a system forces us to rethink the timing and conditions under which rocky planets can form.”

What can rocky planets orbiting in the outer parts of a solar system teach scientists about planetary formation and evolution? This is what a recent study published in Science hopes to address as a team of scientists have discovered a rocky planet orbiting in the outer reaches of an exoplanetary system. This study has the potential to challenge longstanding hypotheses regarding the solar system architecture, specifically regarding rocky planets orbiting closer to their star and larger gas giants orbiting farther away.

For the study, the researchers analyzed four exoplanets in the LHS 1903 system orbiting a red dwarf star, the latter of which is smaller and cooler than our Sun. Due to the planets orbiting closer to their star than our planets orbiting our Sun, the researchers estimated the orbital periods for the four exoplanets were between 2.2 and 29.3 days. However, the researchers were surprised to discover that while the innermost planet was rocky and the second the third planets were gaseous, the outermost planet was also rocky. As a result, this finding contradicts longstanding notions about solar system architecture, specifically regarding our own solar system that rocky planets orbit closer to the star while outer planets are gaseous.

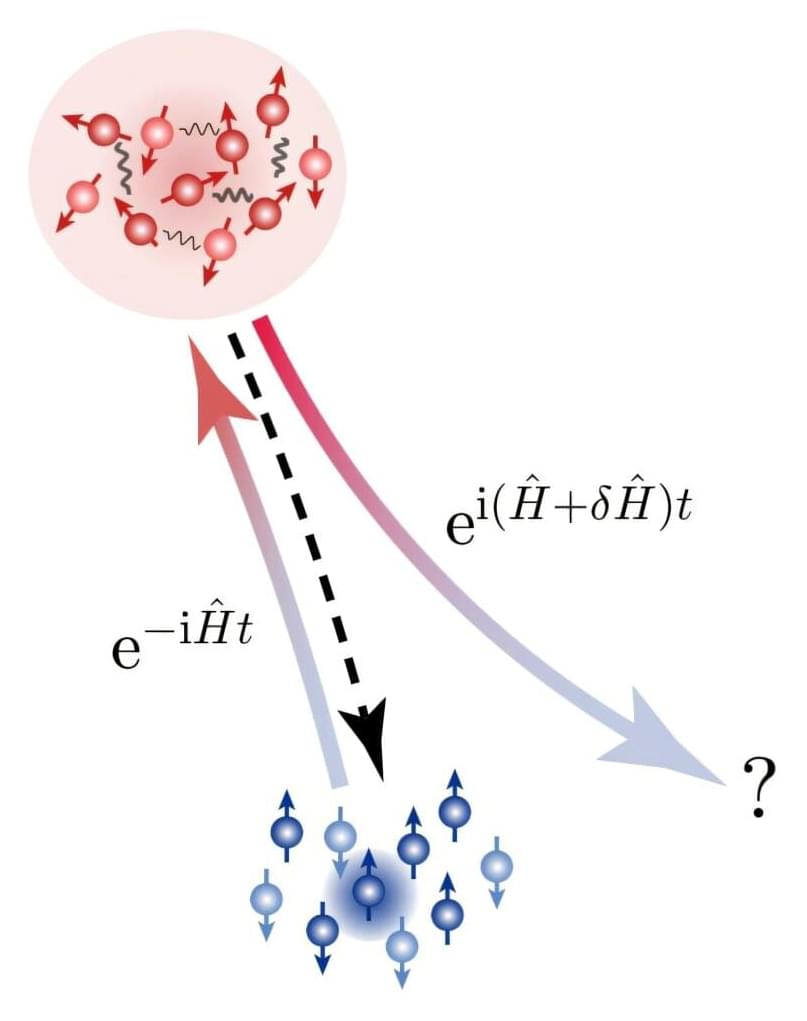

For the first time, researchers in China have accurately quantified how chaos increases in a quantum many-body system as it evolves over time. Combining experiments and theory, a team led by Yu-Chen Li at the University of Science and Technology of China showed that the level of chaos grows exponentially when time reversal is applied to these systems—matching predictions of their extreme sensitivity to errors. The research has been published in Physical Review Letters.

The butterfly effect is a well-known expression of chaos theory. It describes how a complex system can quickly become unpredictable as it evolves: make just a few small errors when specifying the system’s starting conditions, and it may look completely different from your calculations a short time later.

This effect is especially relevant in many-body quantum systems, where entanglement creates intricate webs of interconnection between particles—even in relatively small systems. As the system evolves, information about its initial state becomes increasingly dispersed across these connections.

For every ton of ethylene created, one ton of carbon dioxide is produced. With more than 300 million tons of ethylene produced each year, the production system has a huge carbon footprint that scientists and engineers are eager to reduce and eventually eliminate. A new device developed in Ted Sargent’s lab at Northwestern takes a step toward breaking that cycle.

The device, an electrolyzer, has three innovations. It uses electricity to create ethylene from syngas, a waste gas produced from plastic. It uses a novel material to help catalyze the reaction. And it does so in an efficient way, reducing the overall energy needed for the system.

The results, published Feb. 17 in Nature Energy, can be used with renewable energy sources to help pave the way for a greener ethylene supply chain.

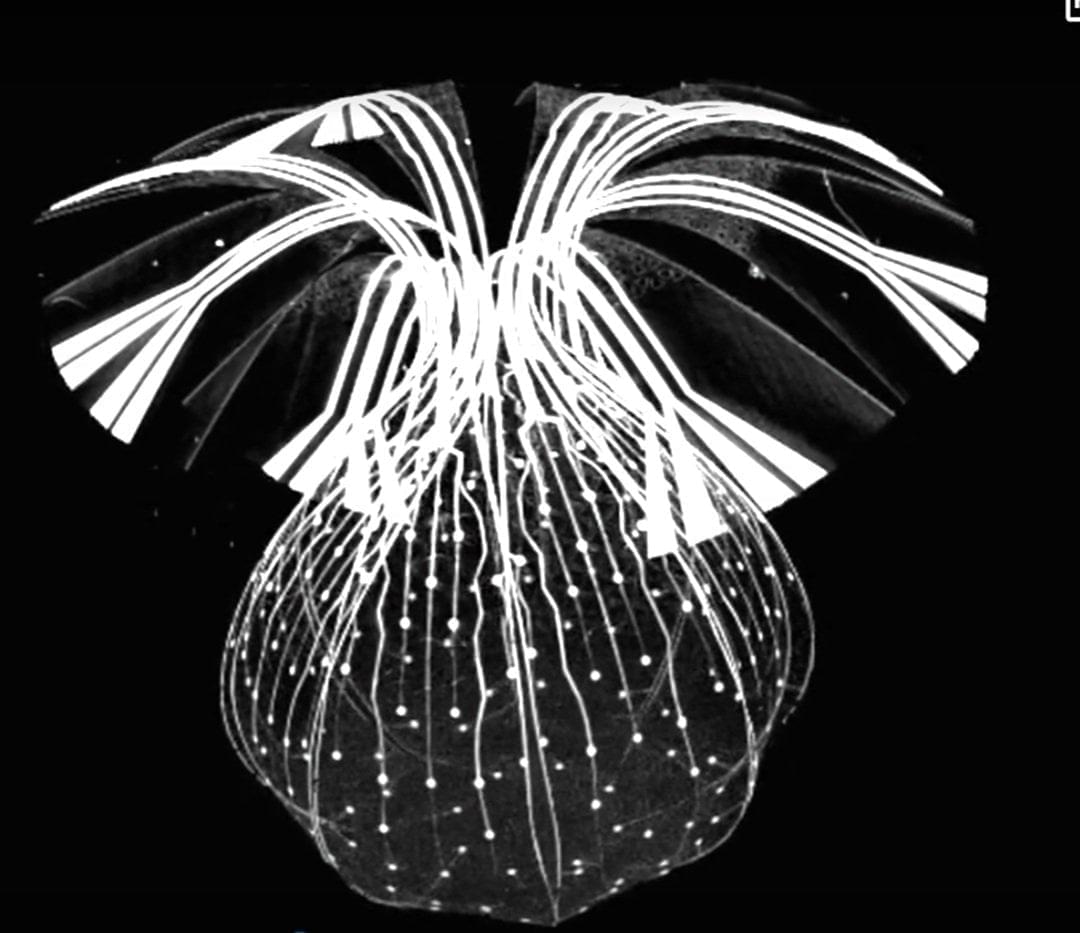

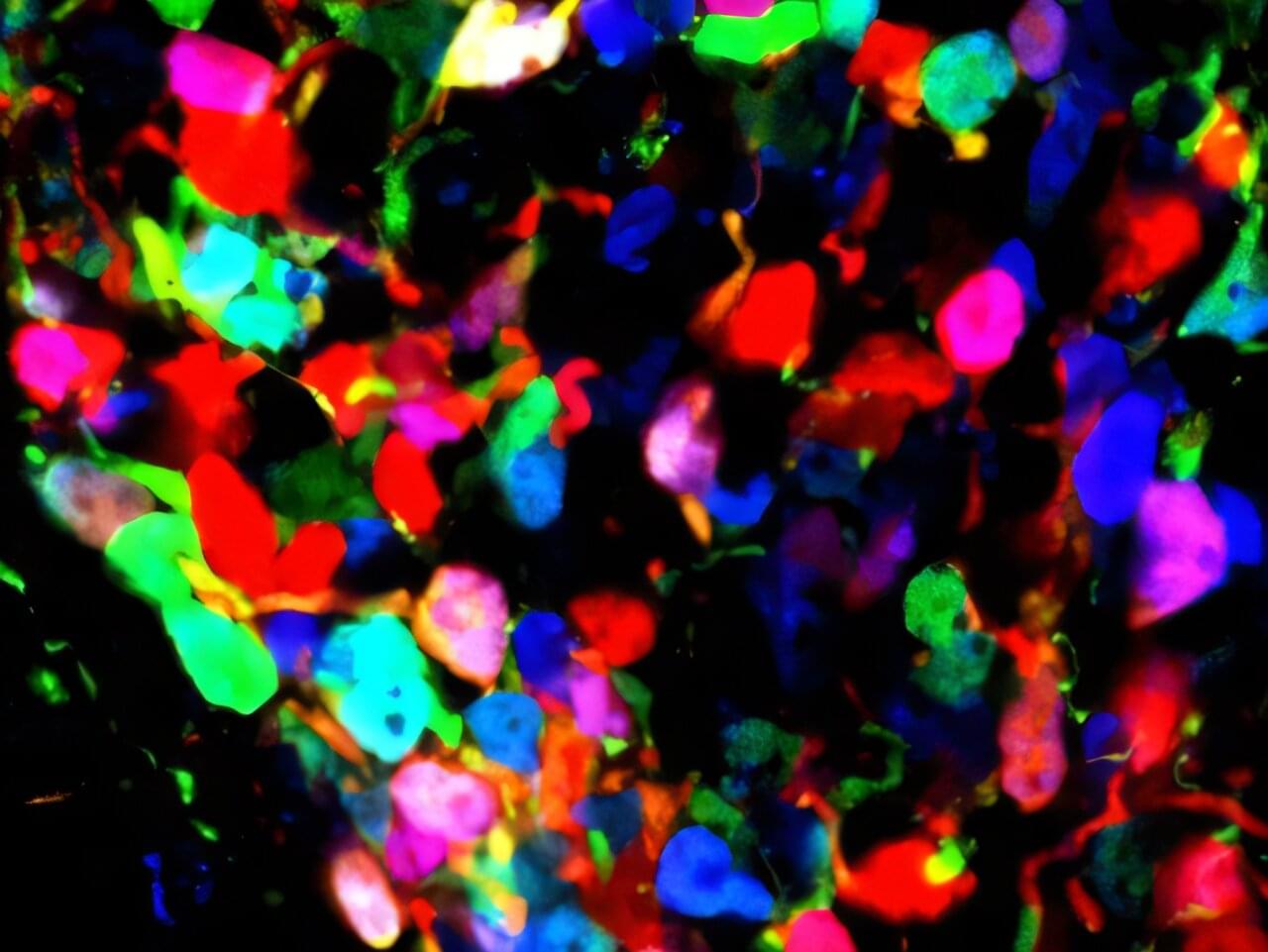

Researchers at UT Southwestern Medical Center have discovered that a crucial developmental process in the brain’s hypothalamus may influence how susceptible individuals are to obesity. Their preclinical findings, published in Neuron, show that a transcription factor called Otp acts as a molecular “switch” that directs immature hypothalamic neurons toward either appetite-suppressing or appetite-stimulating fates—their ultimate identities as specialized cells. The researchers found that disrupting this switch alters feeding behavior and protects mice from diet-induced obesity.

“These findings show that early developmental decisions in the hypothalamus have a long-lasting impact on energy balance,” said senior author Chen Liu, Ph.D., Associate Professor of Internal Medicine and Neuroscience and an Investigator in the Peter O’Donnell Jr. Brain Institute at UT Southwestern.

“By uncovering this fate-switching program, we can begin to understand how the brain establishes lifelong metabolic set points.”

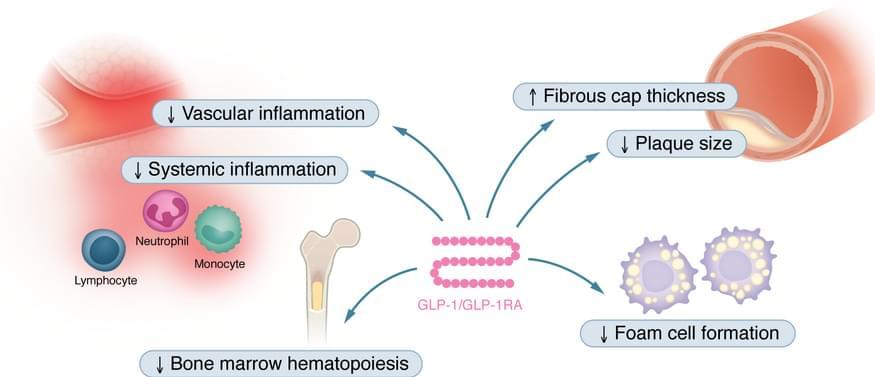

As part of JCI’s Review Series on Clinical Innovation and Scientific Progress in GLP-1 Medicine Florian Kahles, Andreas L. Birkenfeld, & Nikolaus Marx summarize the effects of GLP-1 and GLP-1RAs in the cardiovascular system as well as clinical data of GLP-1RAs in individuals with cardiovascular disease or in those at high risk.

1Department of Internal Medicine I, University Hospital Aachen, RWTH Aachen, Aachen, Germany.

2German Center for Diabetes Research (DZD), Neuherberg, Germany.

3Department of Internal Medicine IV, Diabetology, Endocrinology and Nephrology, Eberhard-Karls University Tübingen, Tübingen, Germany.

An international team of astronomers has performed multi-wavelength observations of the nearby Araish galaxy to investigate the origin of its radio emission. As a result, they detected an extended radio jet of this galaxy. The finding was reported February 11 on the arXiv pre-print server.

Observations show that powerful radio jets are commonly observed in elliptical galaxies or massive quasars. However, their presence in spiral galaxies is relatively rare. These systems, known as spiral double radio-source associated with galactic nuclei (DRAGNs), are therefore unique galaxies where classical disk morphology coexists with large-scale radio jets.

Chikungunya virus, a debilitating tropical disease caused by infected mosquito bites, poses a greater health threat in Europe than previously thought because it can be spread when air temperatures are as low as 13°C. Researchers at the UK Center for Ecology & Hydrology investigated the ability of the Asian tiger mosquito to spread the virus, which is rarely fatal but can cause long-term chronic joint pain.

They drew up a map showing the extent of the risk of chikungunya for 10 km-square areas across Europe including the U.K. The risk map shows the threat of virus transmission may last several months of the year in warmer parts of the continent where the tiger mosquito is already established. The research is published in the Journal of the Royal Society Interface.

There were record numbers of local outbreaks of chikungunya in France and Italy in 2025, and the tiger mosquito has also been responsible for increasing numbers of cases of dengue fever in these countries in recent years. This mosquito species is only occasionally detected in south-east England and is not yet established, so the current risk of local transmission in the U.K. remains very low.