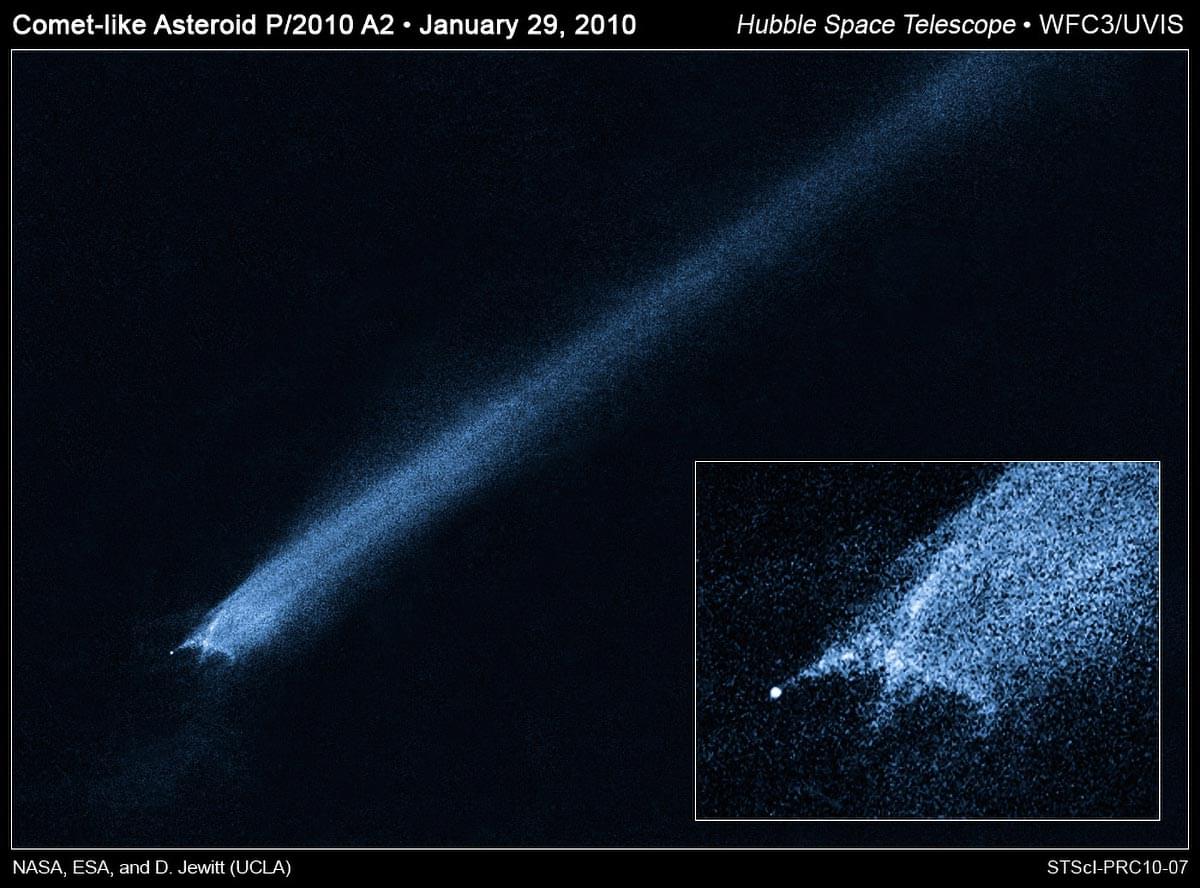

Somewhere, out in the cold depths of space, there is a space rock that could destroy a large chunk of life on Earth. Is this fate inevitable? Could we find a way to stop it, or will we eventually suffer the same fate as the dinosaurs? And should this existential threat be keeping you up at night? Here’s what we know.

The asteroid that killed the dinosaurs 66 million years ago was at least 10 kilometres across, big enough to cause megatsunamis, ignite enormous forest fires and darken the skies the world over. Asteroids of that size are estimated to hit Earth about every 60 million years, based on the planet’s crater record. For the next size class down, asteroids about 1 kilometre across, estimates suggest they hit Earth about every million years, and the most recent one was about 900,000 years ago. Those numbers are enough to make you nervous.

But one of the things that sets humanity apart from the dinosaurs is our ability to look out into space and interpret what we see there. Naturally, researchers around the world have used this ability to attempt to learn how many asteroids are out there and what proportion of them are on trajectories that could be dangerous.

Image: angel_nt/Getty Images.

The dinosaurs were wiped out by an asteroid, but does that mean we risk suffering the same fate — and should you be worried about the possibility? Leah Crane sets the matter straight.

By Leah Crane