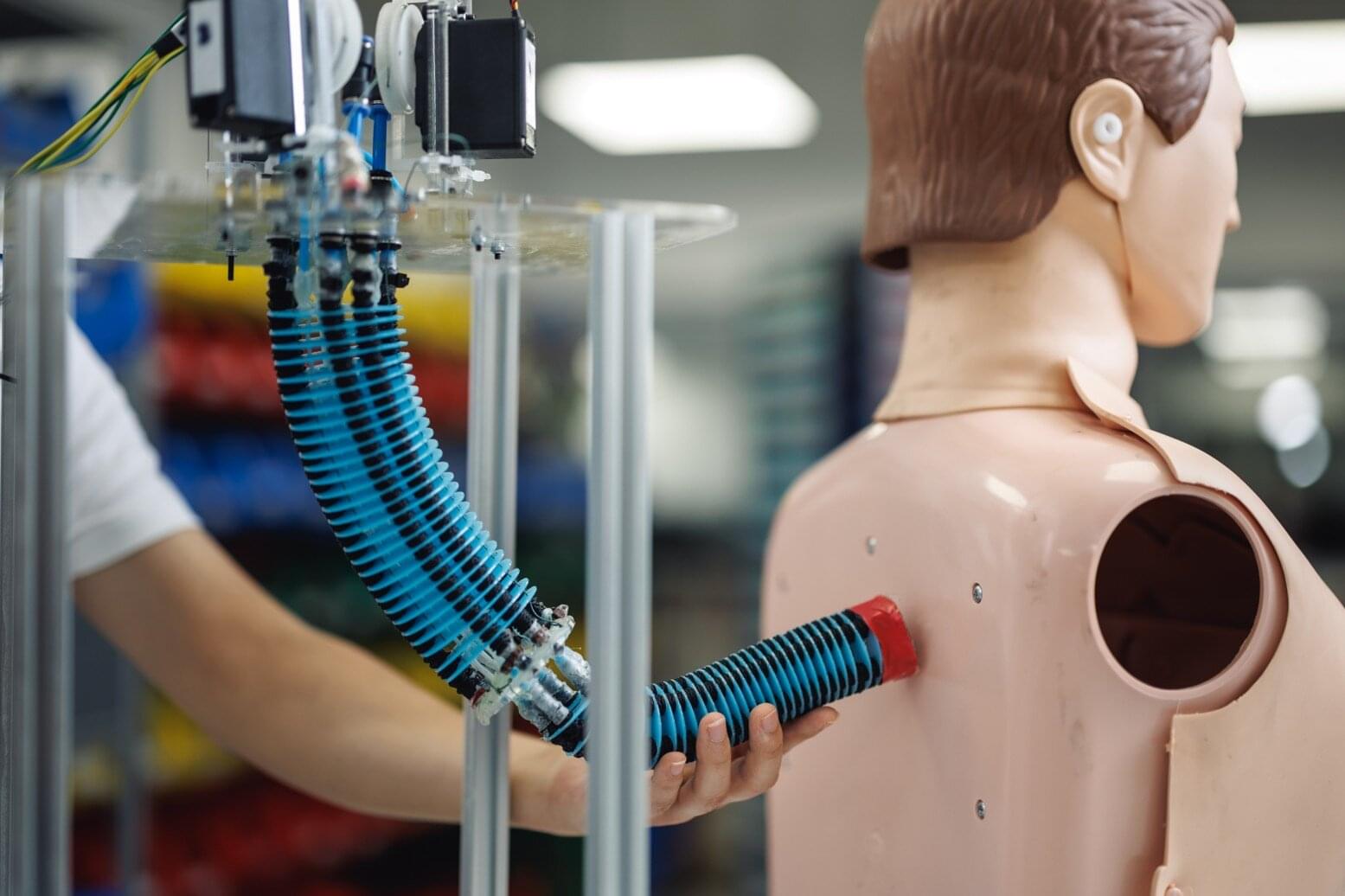

Researchers have developed an AI control system that enables soft robotic arms to learn a wide repertoire of motions and tasks once, then adjust to new scenarios on the fly without needing retraining or sacrificing functionality. This breakthrough brings soft robotics closer to human-like adaptability for real-world applications, such as in assistive robotics, rehabilitation robots, and wearable or medical soft robots, by making them more intelligent, versatile, and safe. The research team includes Singapore-MIT Alliance for Research and Technology’s (SMART) Mens, Manus & Machina (M3S) interdisciplinary research group, and National University of Singapore (NUS), alongside collaborators from Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and Nanyang Technological University (NTU Singapore).

Unlike regular robots that move using rigid motors and joints, soft robots are made from flexible materials such as soft rubber and move using special actuators—components that act like artificial muscles to produce physical motion. While their flexibility makes them ideal for delicate or adaptive tasks, controlling soft robots has always been a challenge because their shape changes in unpredictable ways. Real-world environments are often complicated and full of unexpected disturbances, and even small changes in conditions—like a shift in weight, a gust of wind, or a minor hardware fault—can throw off their movements.