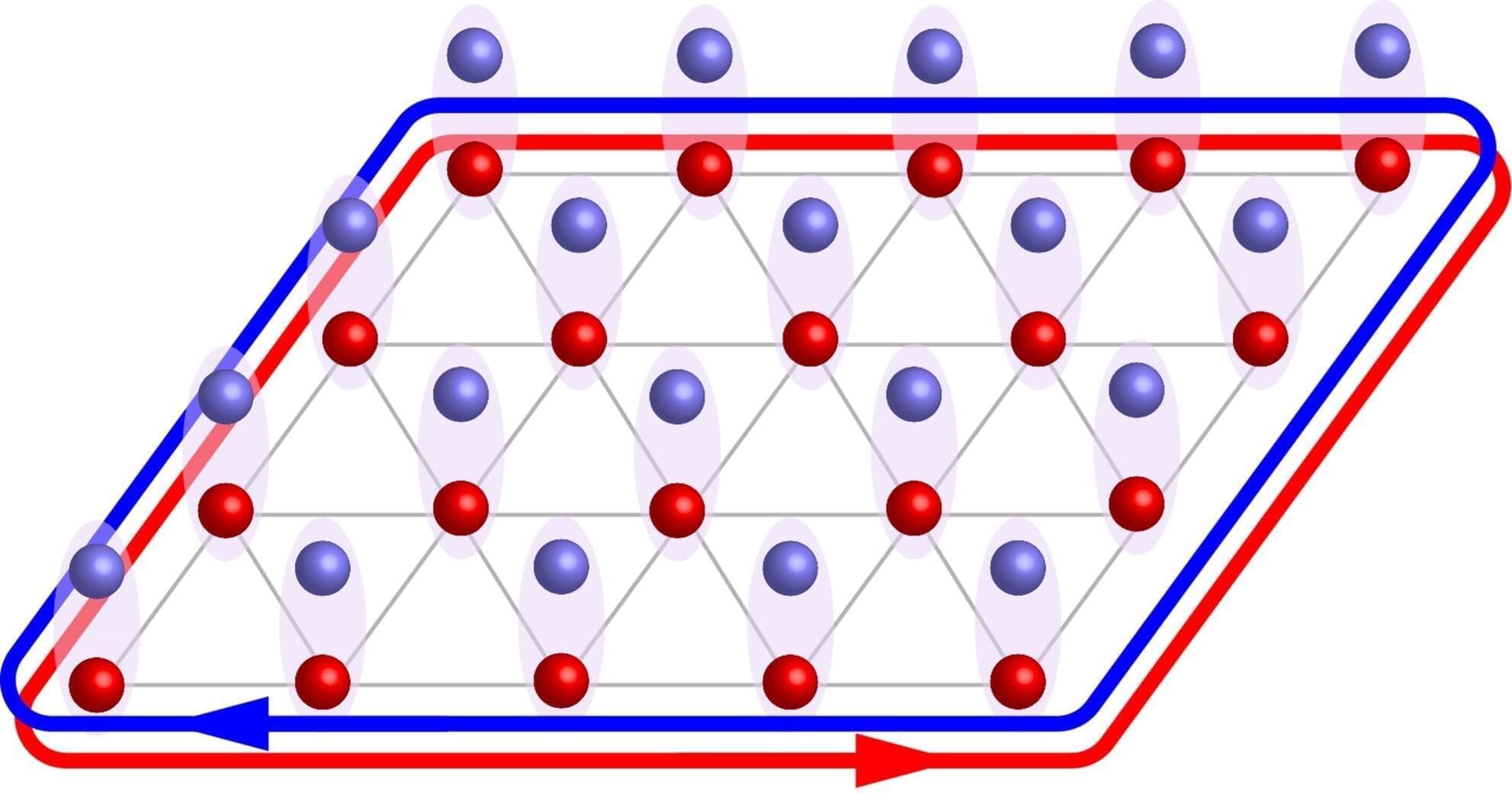

When mobile charge carriers, also known as itinerant electrons, interact with the strong exchange magnetic fields associated with the intrinsic angular momentum of localized electrons, this can give rise to the so-called Kondo effect. A Kondo insulator is a state of matter with an energy gap opened by the Kondo effect that forbids electrical conduction at low temperatures.

Like Kondo insulators, topological Kondo insulators are materials that behave as insulators (i.e., not conducting electricity) in their interior, but, unlike their counterparts without topology, can conduct electricity at their surface or edges. This unique, quantum phase of matter is protected by a material’s internal symmetry and topology; thus, it is not easily disrupted.

So far, hints of this phase have been primarily observed in 3D quantum materials, such as samarium hexaboride (SmB₆) and ytterbium dodecaboride. Some physicists and material scientists have also been exploring the possible existence of this phase in 2D structures comprised of two materials stacked with a slight mismatch between them, producing a pattern known as a moiré superlattice.