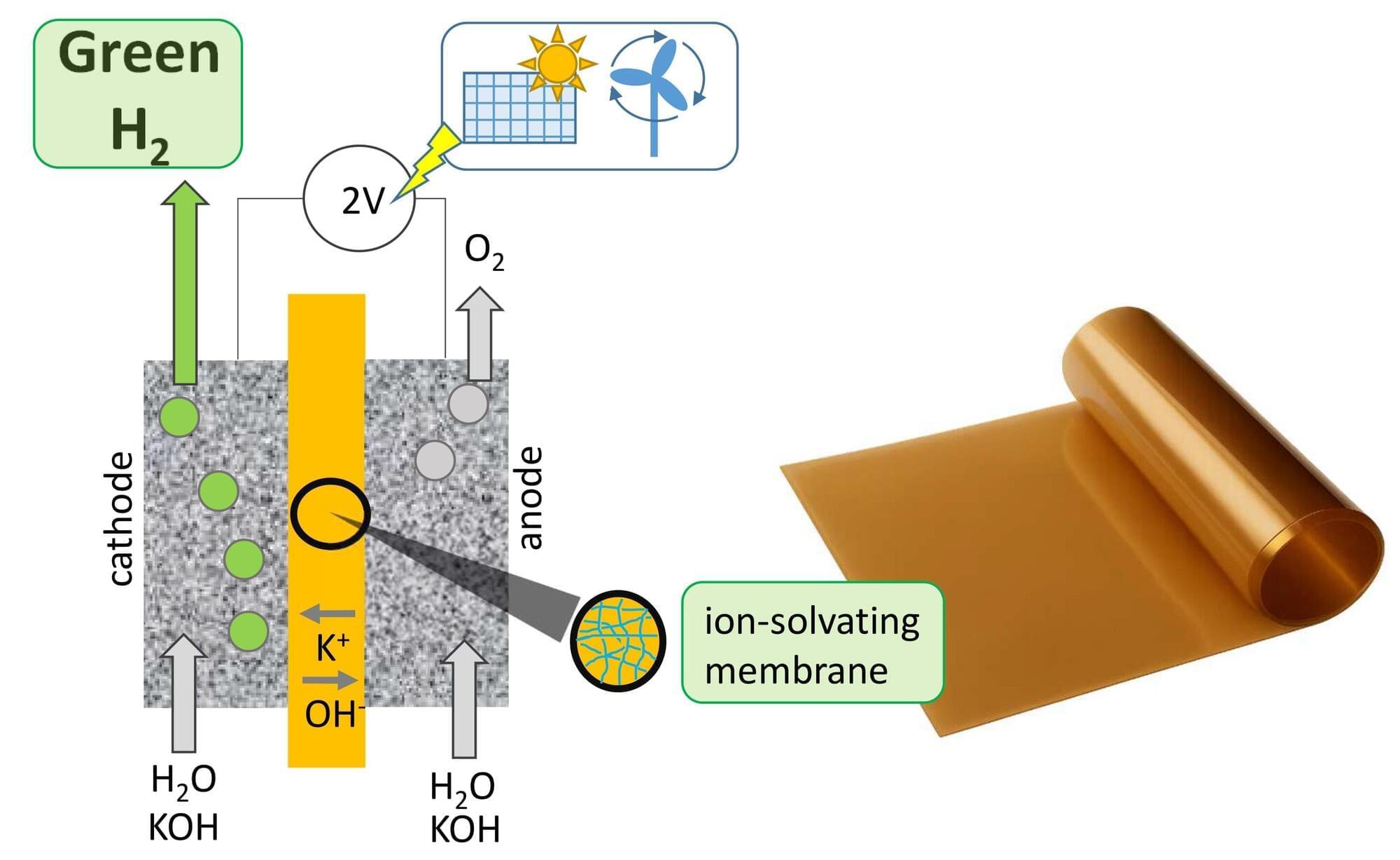

As green hydrogen emerges as a key next-generation clean energy source, securing technologies that enable its stable and cost-effective production has become a critical challenge. However, conventional water electrolysis technologies face limitations in large-scale deployment due to high system costs and operational burdens.

In particular, long-term operation often leads to performance degradation and increased maintenance costs, hindering commercialization. As a result, there is growing demand for new electrolysis technologies that can simultaneously improve efficiency, stability, and cost competitiveness.

A research team led by Dr. Dirk Henkensmeier at the Hydrogen and Fuel Cell Research Center of the Korea Institute of Science and Technology (KIST) has developed a novel membrane material for water electrolysis that operates stably and has significantly higher conductivity under low alkalinity conditions than existing systems.