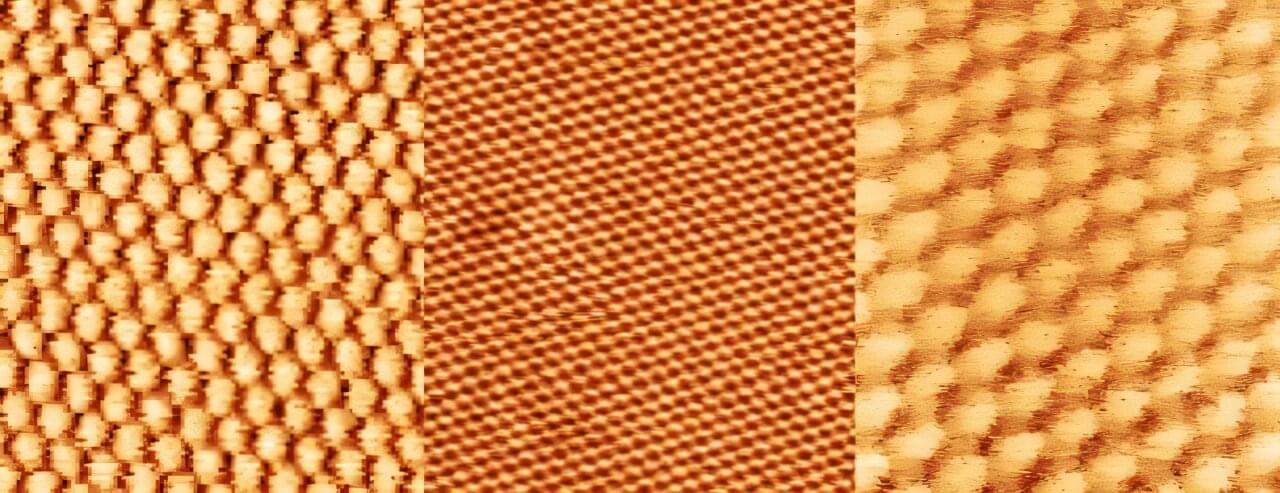

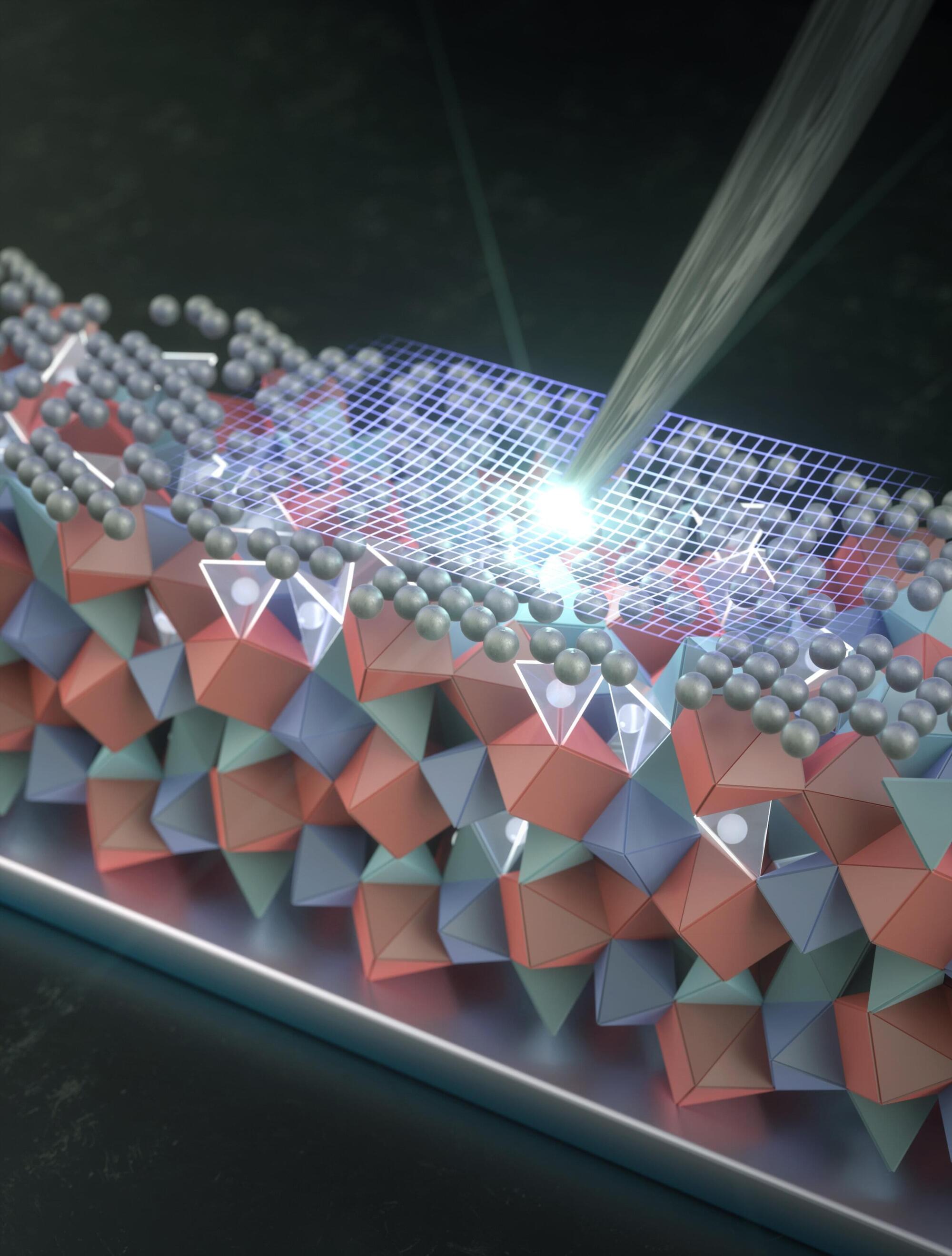

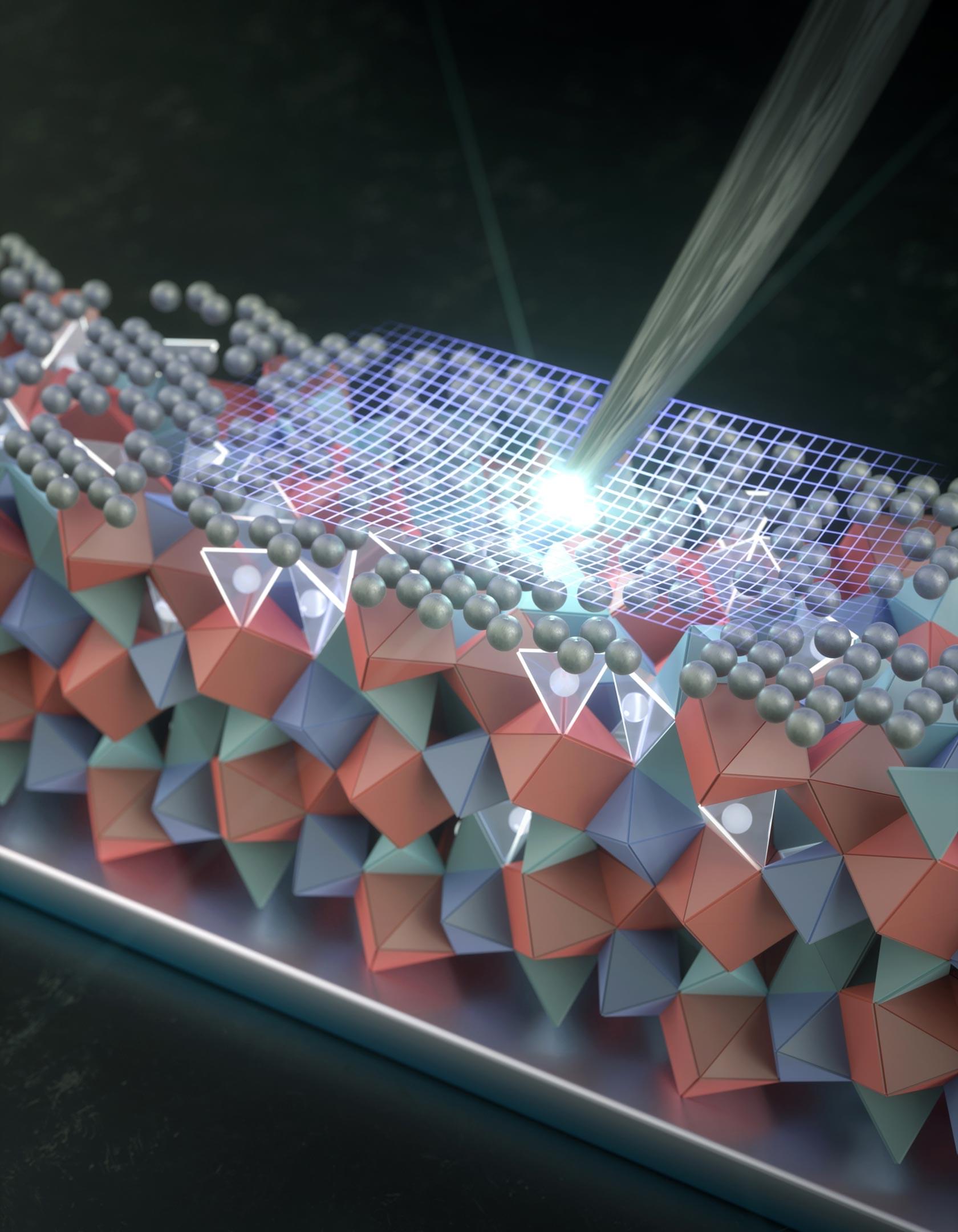

Exciting electronic characteristics emerge when scientists stack 2D materials on top of each other and give the top layer a little twist.

The twist turns a normal material into a patterned lattice and changes the quantum behavior of the material. These twisted materials have shown superconductivity—where a material can conduct electricity without energy loss—as well as special quantum effects. Researchers hope these “twistronics” could become components in future quantum devices.

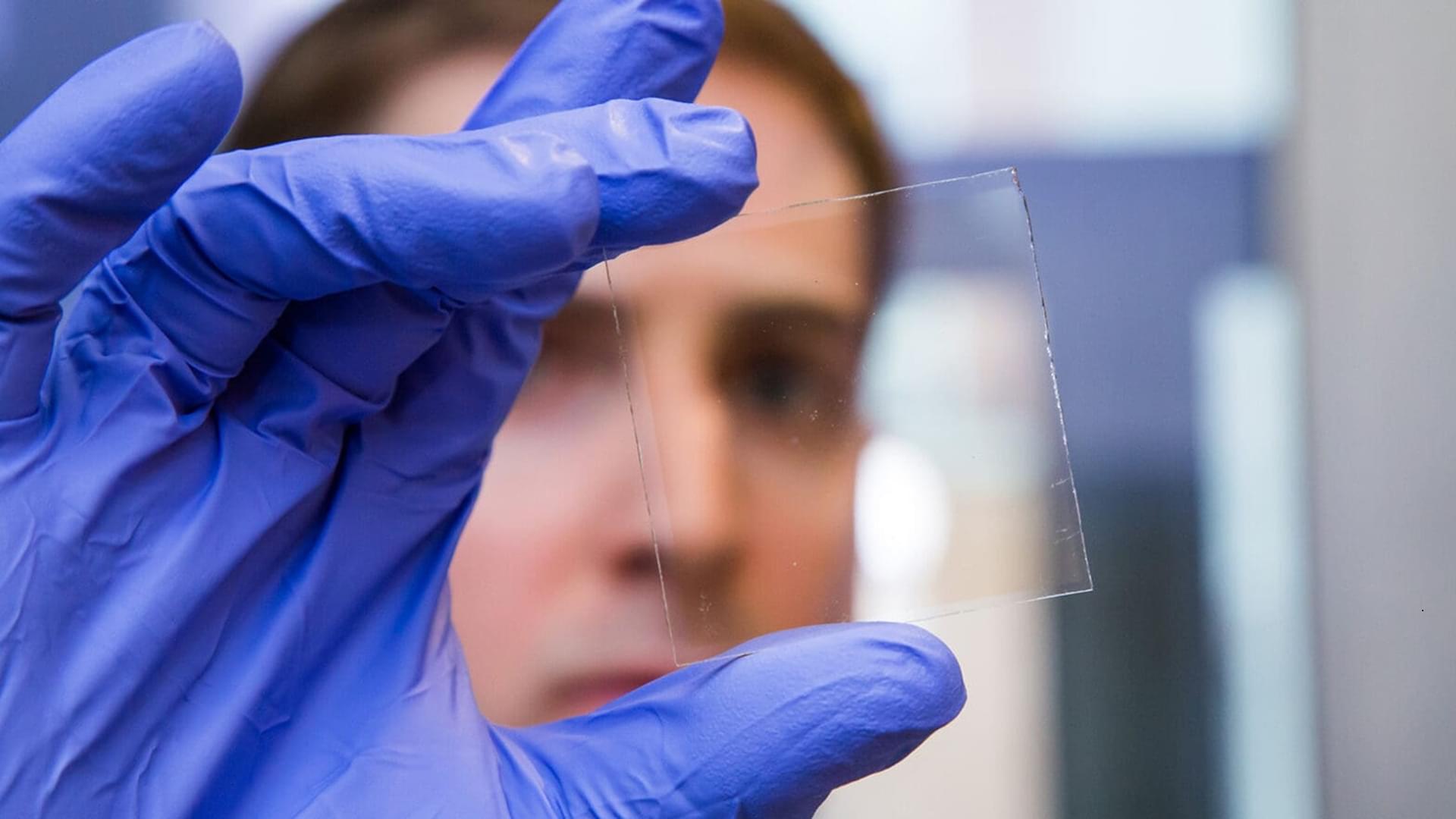

But creating these extremely thin stacked structures, called moiré superlattices, is difficult to do. Scientists usually peel off single layers of material using Scotch tape and then carefully stick those layers together. However, the method has a very low success rate, often leaves behind contamination between layers and produces tiny samples smaller than the width of a human hair.