This study represents a characterization of pediatric Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease in a Canadian cohort and demonstrates that disease onset, severity, and manifestations are highly variable even in childhood.

Background and Objectives.

For this study, the researchers focused on a type of colorectal cancer that accounts for 80% to 85% of all colorectal cancers — microsatellite stable (MSS) with proficient mismatch repair (MMRp), meaning the tumors’ DNA is relatively stable. These cancers are largely resistant to checkpoint inhibitor immunotherapies.

Previous groundbreaking research found checkpoint inhibitors alone could successfully treat rectal cancer and several other cancers with the opposite tumor type — those with high microsatellite instability (MSI-H) and mismatch repair deficiency (MMRd). This allows doctors to spare many patients from surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation.

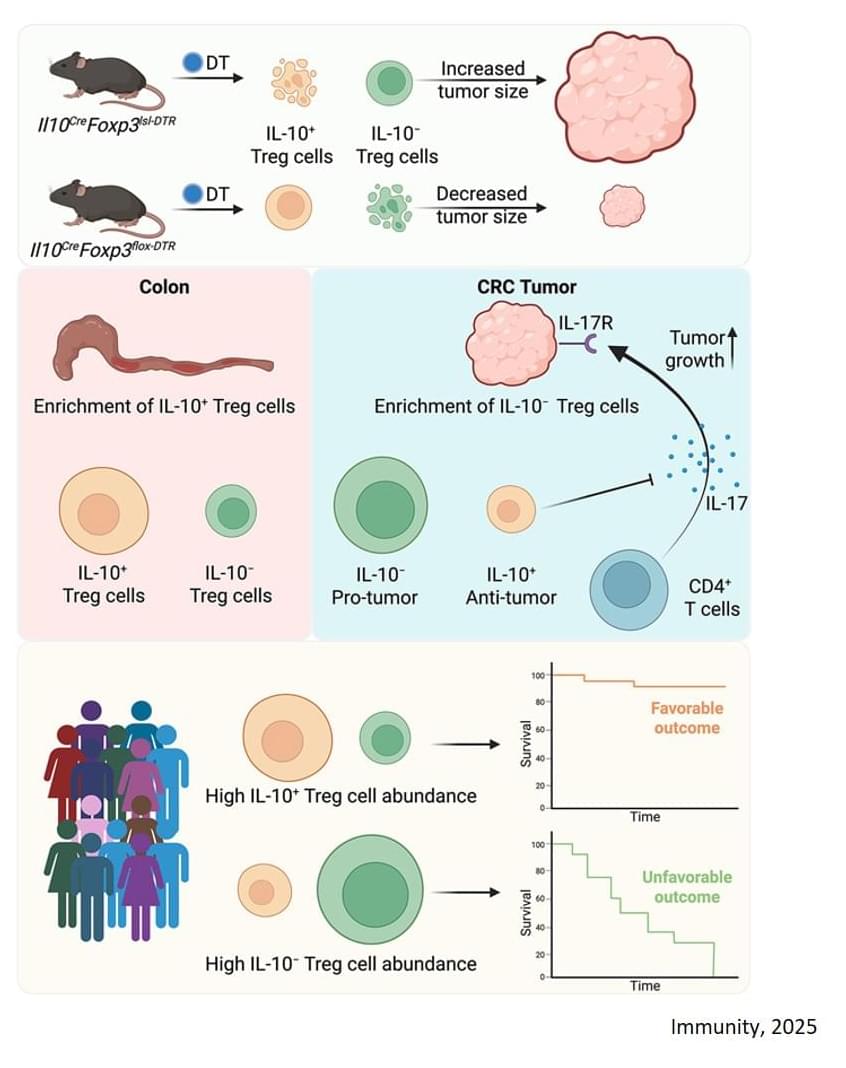

Here the team employed an mouse model that accurately recreates the common mutations, behaviors, and immune cell composition of human colorectal cancer. They found that the regulatory T cells associated with the cancer are split between two types: Cells that make a signaling molecule (cytokine) called interleukin‑10 (IL-10) and cells that don’t.

Through a series of sophisticated experiments that selectively eliminated each type of cell, the researchers discovered:

When IL-10-positive cells were removed, tumor growth accelerated.

In most solid tumors, high numbers of regulatory T (Treg) cells are associated with poorer outcomes because they dampen the immune system’s ability to fight against a tumor.

By Nina Bai

Stanford Medicine researchers recorded stem cells performing a previously unknown type of movement, dubbed cell tumbling, which may help them differentiate.

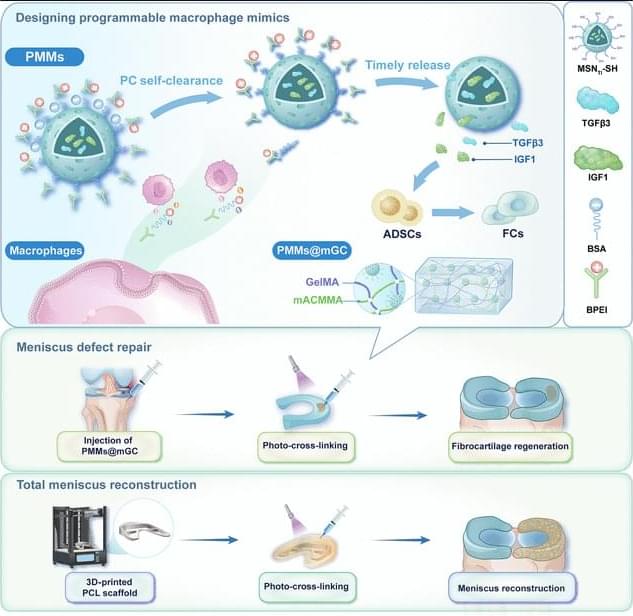

JUST PUBLISHED: programmable macrophage mimics for inflammatory meniscus regeneration via nanotherapy

Click here to read the latest free, Open Access Article from Research.

The meniscus is a fibrocartilaginous tissue and organ in the human knee joint that serves critical functions, including load transmission, shock absorption, joint stability, and lubrication. Meniscal injuries are among the most common knee injuries, typically caused by acute trauma or age-related degeneration [1– 3]. Minor meniscal injuries are usually treated with in situ arthroscopic procedures or conservative methods, whereas larger or more severe injuries often necessitate total meniscus replacement. Recent advances in materials science and manufacturing techniques have enabled transformative tissue-engineering strategies for meniscal therapy [4, 5]. Several stem cell types, including synovium-derived mesenchymal stem cells, bone-marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells, and adipose-derived stem cells (ADSCs), have been investigated as candidate seed cells for meniscal regeneration and repair. Notably, ADSCs are clinically promising because of their ease of harvest, high inducibility, innate anti-inflammatory properties, and potential to promote fibrocartilage regeneration [6– 8]. Our group has developed a series of decellularized matrix scaffolds for auricular, nasal, tracheal, and articular cartilage repair using 3-dimensional (3D) bioprinting techniques, successfully repairing meniscus defects and restoring physiological function [9– 12]. However, current tissue-engineering strategies for meniscus defect repair commonly rely on a favorable regenerative microenvironment. Pathological conditions such as osteoarthritis (OA) [13 – 16], the most prevalent joint disorder, often create inflammatory environments that severely hinder meniscus regeneration [17 – 21]. Moreover, meniscal injury exacerbates the local inflammatory milieu, further impeding tissue healing and inevitably accelerating OA progression. Therefore, there is an urgent need to establish a cartilaginous immune microenvironment that first mitigates early-stage inflammation after meniscal injury and then sequentially promotes later-stage fibrocartilage regeneration [22 – 25].

Currently, targeted regulation using small-molecule drug injections is commonly employed to treat inflammatory conditions in sports medicine [26,27]. Most of these drugs exhibit broad-spectrum anti-inflammatory effects and inevitably cause varying degrees of side effects by activating nonspecific signaling pathways. Polyethyleneimine is a highly cationic polymer. It is widely used to modulate inflammation by adsorbing and removing negatively charged proinflammatory cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin-1β (IL-1β), and interleukin-6 (IL-6), via electrostatic interactions [28–31]. Notably, modifying polyethyleneimine into its branched form (branched polyethyleneimine [BPEI]) has been shown to improve cytocompatibility and enhance in vivo metabolic cycling.

Organs often have fluid-filled spaces called lumens, which are crucial for organ function and serve as transport and delivery networks. Lumens in the pancreas form a complex ductal system, and its channels transport digestive enzymes to the small intestine. Understanding how this system forms in embryonic development is essential, both for normal organ formation and for diagnosing and treating pancreatic disorders. Despite their importance, how lumens take certain shapes is not fully understood, as studies in other models have largely been limited to the formation of single, spherical lumens. Organoid models, which more closely mimic the physiological characteristics of real organs, can exhibit a range of lumen morphologies, such as complex networks of thin tubes.

Researchers in the group of Anne Grapin-Botton, director at the Max Planck Institute of Molecular Cell Biology and Genetics (MPI-CBG) in Dresden, Germany, and also Honorary Professor at TU Dresden, teamed up with colleagues from the group of Masaki Sano at the University of Tokyo (Japan), Tetsuya Hiraiwa at the Institute of Physics of Academia Sinica (Taiwan), and with Daniel Rivéline at the Institut de Génétique et de Biologie Moléculaire et Cellulaire (France) to explore the processes involved in complex lumen formation. Working with a combination of computational modeling and experimental techniques, the scientists were able to identify the crucial factors that control lumen shape.

Three-dimensional pancreatic structures, also called pancreatic organoids, can form either large spherical lumen or narrow complex interconnected lumen structures, depending on the medium in the dish. By adding specific chemical drugs altering cell proliferation rate and pressure in the lumen, we were able to change lumen shape. We also found that making the epithelial cells surrounding the lumen more permeable reduces pressure and can change the shape of the lumen as well.

A study being conducted at The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, led by Professor Sagiv Shifman, found that many genes are essential for healthy brain cell development, but only a small share are currently connected to recognized neurodevelopmental disorders.

Read more from ynet here.

The researchers also identified clear patterns in how different genes contribute to disease. Genes that regulate other genes, such as transcription and chromatin regulators, were more often linked to dominant disorders, where a mutation in a single copy of a gene can cause illness. In contrast, genes involved in metabolic processes were typically associated with recessive disorders, requiring mutations in both copies of the gene.

To validate their findings, the team studied eight genes in mouse models — including PEDS1, EML1 and SGMS1 — and found major abnormalities in brain structure. In four of the cases, the mice developed microcephaly, a condition marked by an abnormally small brain.

One gene, PEDS1, emerged as particularly significant. The gene plays a key role in producing plasmalogens, a class of lipids essential to cell membranes and nerve tissue. When PEDS1 was disabled in mice, brain cells exited the cell cycle too early and failed to properly differentiate and migrate, severely impairing brain development.

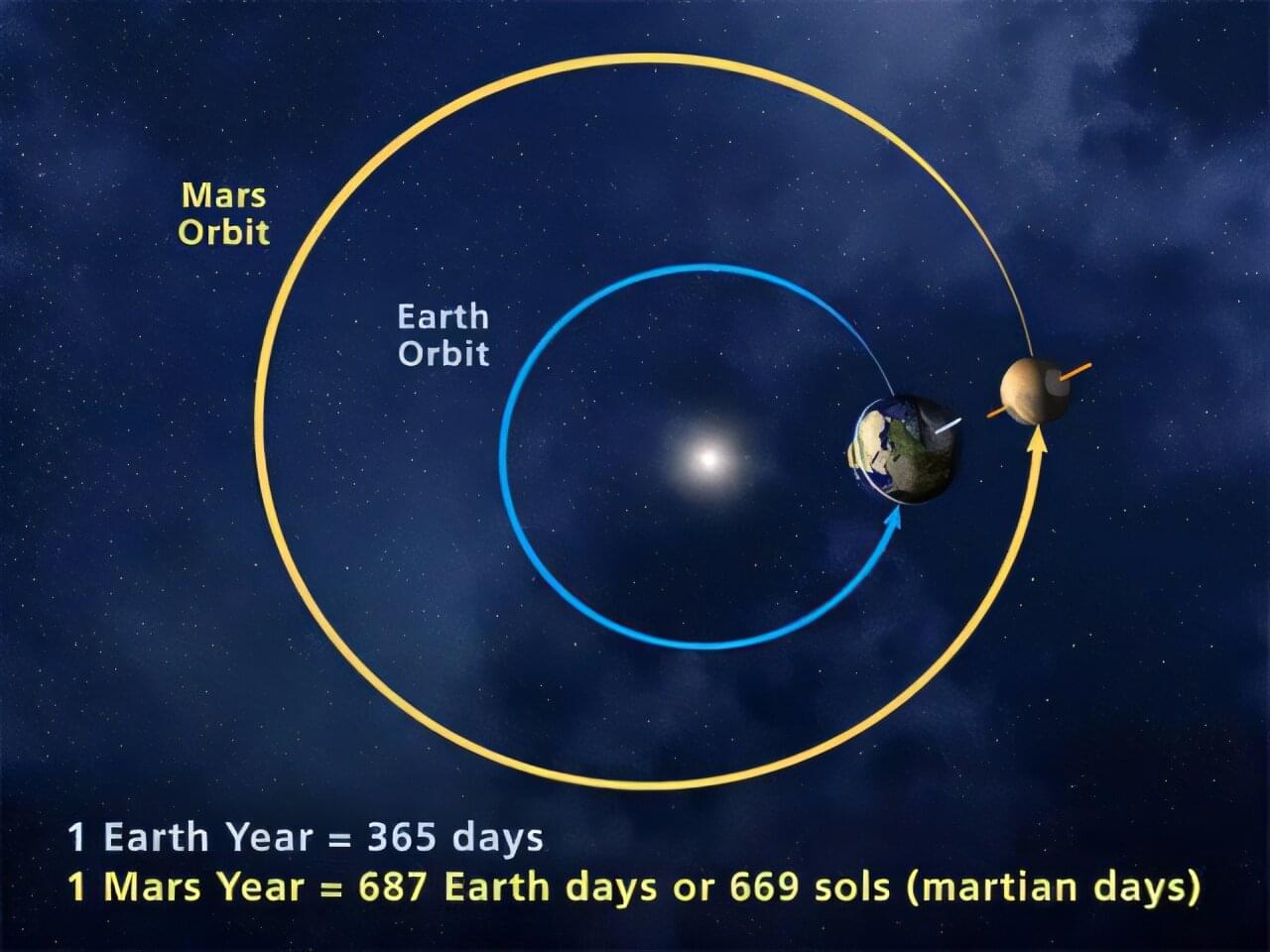

At half the size of Earth and one-tenth its mass, Mars is a featherweight as far as planets go. Yet new research reveals the extent to which Mars is quietly tugging on Earth’s orbit and shaping the cycles that drive long-term climate patterns here, including ice ages.

The study is published in the journal Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific.

Stephen Kane, a professor of planetary astrophysics at UC Riverside, began this project with doubts about recent studies tying Earth’s ancient climate patterns to gravitational nudges from Mars. These studies suggest that sediment layers on the ocean floor reflect climate cycles influenced by the red planet despite its distance from Earth and small size.

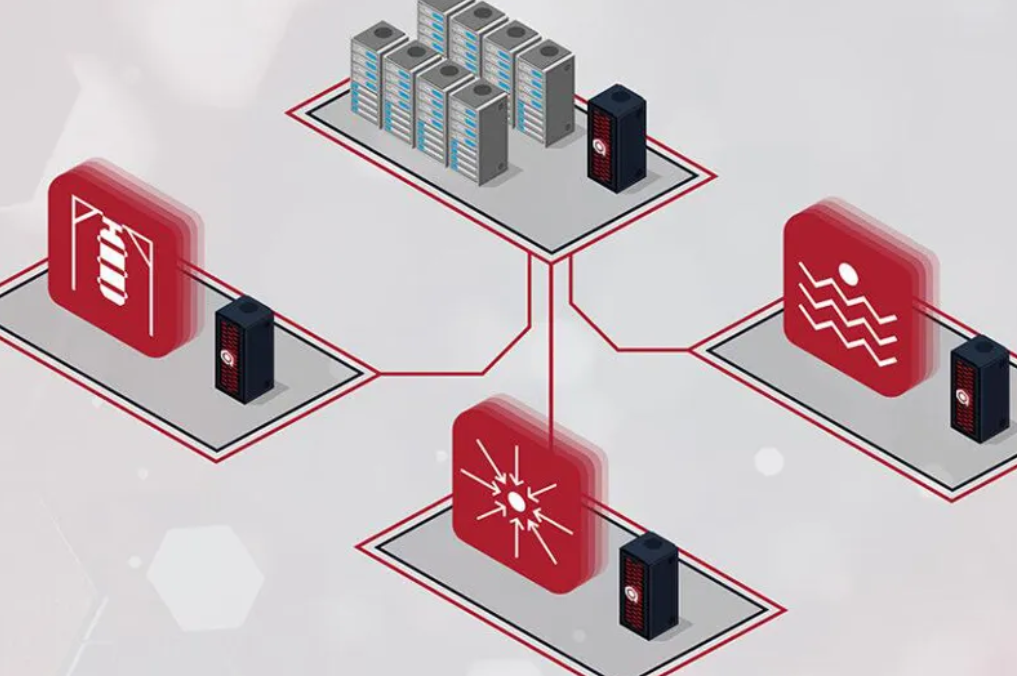

How Plasma Control Will Make Fusion Power Possible — Dr. Marco De Baar Ph.D. — Dutch Institute for Fundamental Energy Research (DIFFER) / TU Eindhoven.

Dr. Marco de Baar, Ph.D. is a full professor and Chair of Plasma Fusion Operation and Control at the Mechanical Engineering Faculty of Eindhoven University of Technology (TU/e — https://www.tue.nl/en/research/resear…

In addition to his work at TU/e, Dr. de Baar is also head of fusion research at the Dutch Institute for Fundamental Energy Research (DIFFER — https://www.differ.nl/) located on the TU/e campus. As member of DIFFER’s management team, he has also served as the Dutch representative in the European fusion research consortium EUROfusion (https://euro-fusion.org/).

From 2004 to 2007, Dr. de Baar headed the operations department at JET (Joint European Torus), Europe’s largest fusion experiment to date, where he was responsible for the successful operation and development of the reactor. From 2007, he was deputy project leader in the international consortium that develops the upper port launcher. He is program-leader for the Magnetohydrodynamics stabilization work package in ITER-NL (International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor — https://www.iter.org/).

Dr. de Baar’s main scientific interest is the control of nuclear fusion plasmas, with a focus on control of Magnetohydrodynamics modes (for plasma stability) and current density profile (for performance optimization). In his research program, all elements of the control loops are considered, including actuator and sensor design, and advanced control oriented modelling. He also has a keen interest in the operations and the remote maintainability of nuclear fusion reactors.

PRESS RELEASE — The Department of Energy has renewed funding for the Quantum Science Center, with Los Alamos National Laboratory continuing to play a vital role along with Oak Ridge National Laboratory in the center’s mission to advance quantum science and technology. The center will be funded for $125 million over five years to focus on quantum-accelerated high-performance computing.

“The Quantum Science Center is establishing the scientific and technical foundation for quantum computing,” said Mark Chadwick, associate Laboratory director for Simulation, Computing and Theory. “In this new, critical evolution for the center, the integration of quantum and high-performance computing stands to accelerate advancements in crucial scientific areas related to technological progress and even national security applications.”

The Quantum Science Center combines the efforts of three national laboratories, with ORNL hosting the center and Los Alamos a principal partner alongside various universities, industry partners and other laboratories. Created as one of five National Quantum Information Science Research Centers supported by the DOE’s Office of Science, the Quantum Science Center seeks to create a scientific ecosystem for the advancement of fault-tolerant, quantum-accelerated high-performance computing.