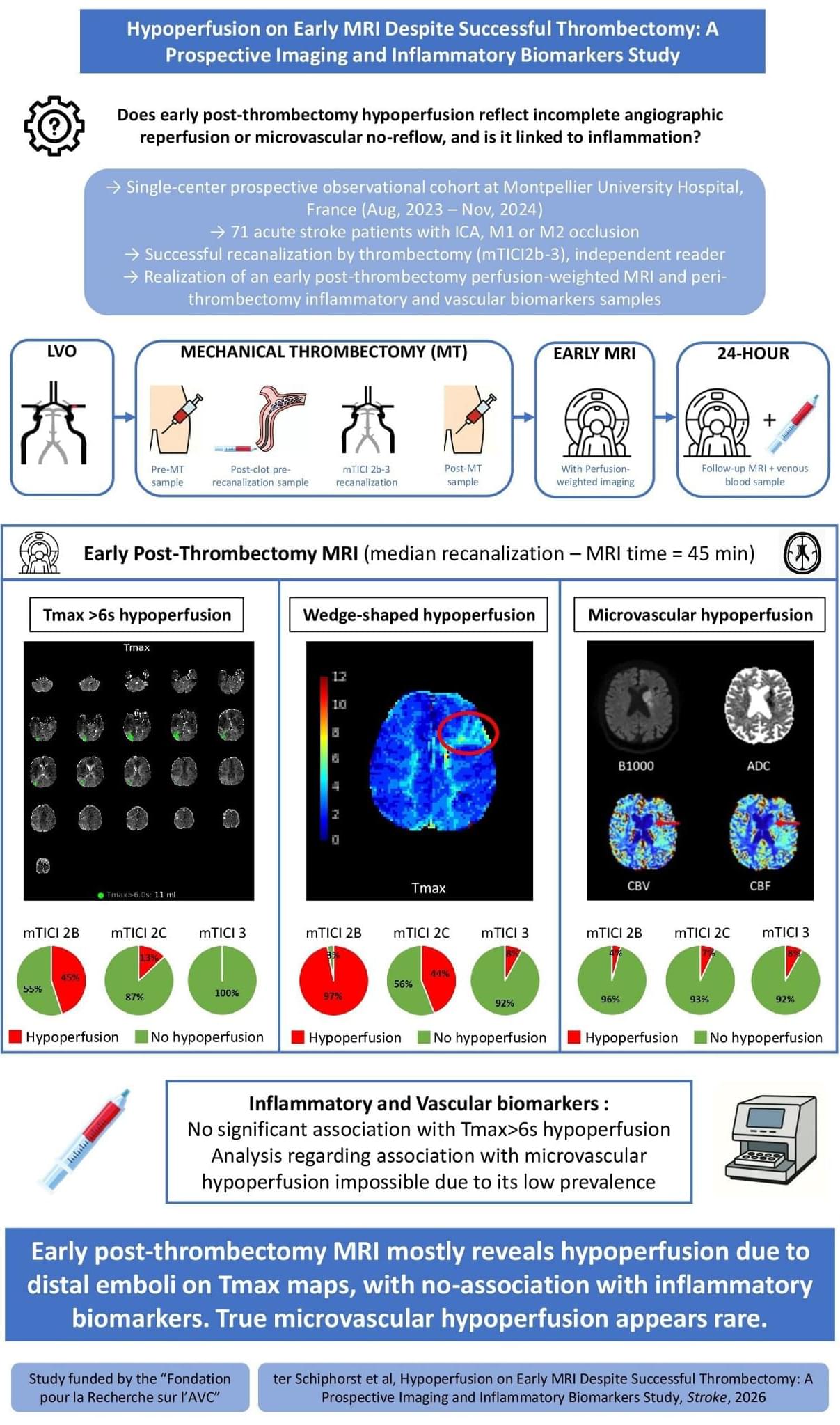

ISC26 After successful EVT for stroke, early MRI shows residual hypoperfusion in a substantial subset of patients. Perfusion deficits mainly reflected distal emboli and were not associated with inflammatory biomarkers.

In acute ischemic stroke (AIS) due to large-vessel occlusion (LVO), endovascular treatment (EVT) achieves over 80% recanalization rates and improves functional outcomes.1 However, nearly half of recanalized patients fail to achieve functional independence,1 a phenomenon termed futile recanalization.2,3 Mechanisms of futile recanalization include early extensive infarct core—that is, tissue that is already irreversibly damaged at the time of reperfusion—as well as edema, hemorrhagic transformation, and no-reflow.3 The latter, defined as impaired capillary reperfusion despite angiographic success, has gained increasing attention.4–15

In experimental models, no-reflow occurs early after arterial reopening and is driven by multifactorial microvascular dysfunction.16–19 Reported mechanisms include astrocyte and endothelial swelling, pericyte contraction, leukocytes, platelets and erythrocytes aggregation, and the release of inflammatory mediators.20–24 Regarding the latter, cytokines and adhesion molecules have been implicated in its pathogenesis in preclinical studies.24 These findings have led to the hypothesis that inflammation may contribute to microvascular perfusion failure after EVT, potentially opening the door to targeted therapeutic interventions.20–24 However, this has never been systematically investigated in humans.

In clinical practice, persistent hypoperfusion on post-EVT computed tomography (CT) perfusion or magnetic resonance perfusion imaging is frequently interpreted as a radiological correlate of no-reflow.4–15 Yet this interpretation remains uncertain. First, no direct histological evidence of no-reflow has been demonstrated in human stroke to date. Second, most imaging-based studies on no-reflow have included patients with residual distal emboli,10,12,25 which cause residual hypoperfusion on a macrovascular level.26 Third, many studies did not exclude confounders, such as perfusion abnormalities caused by carotid stenosis, parenchymal hemorrhage, or reocclusion.14 These limitations may explain the wide variability in the reported prevalence of postthrombectomy hypoperfusion, from 0% to 80%.14,25.