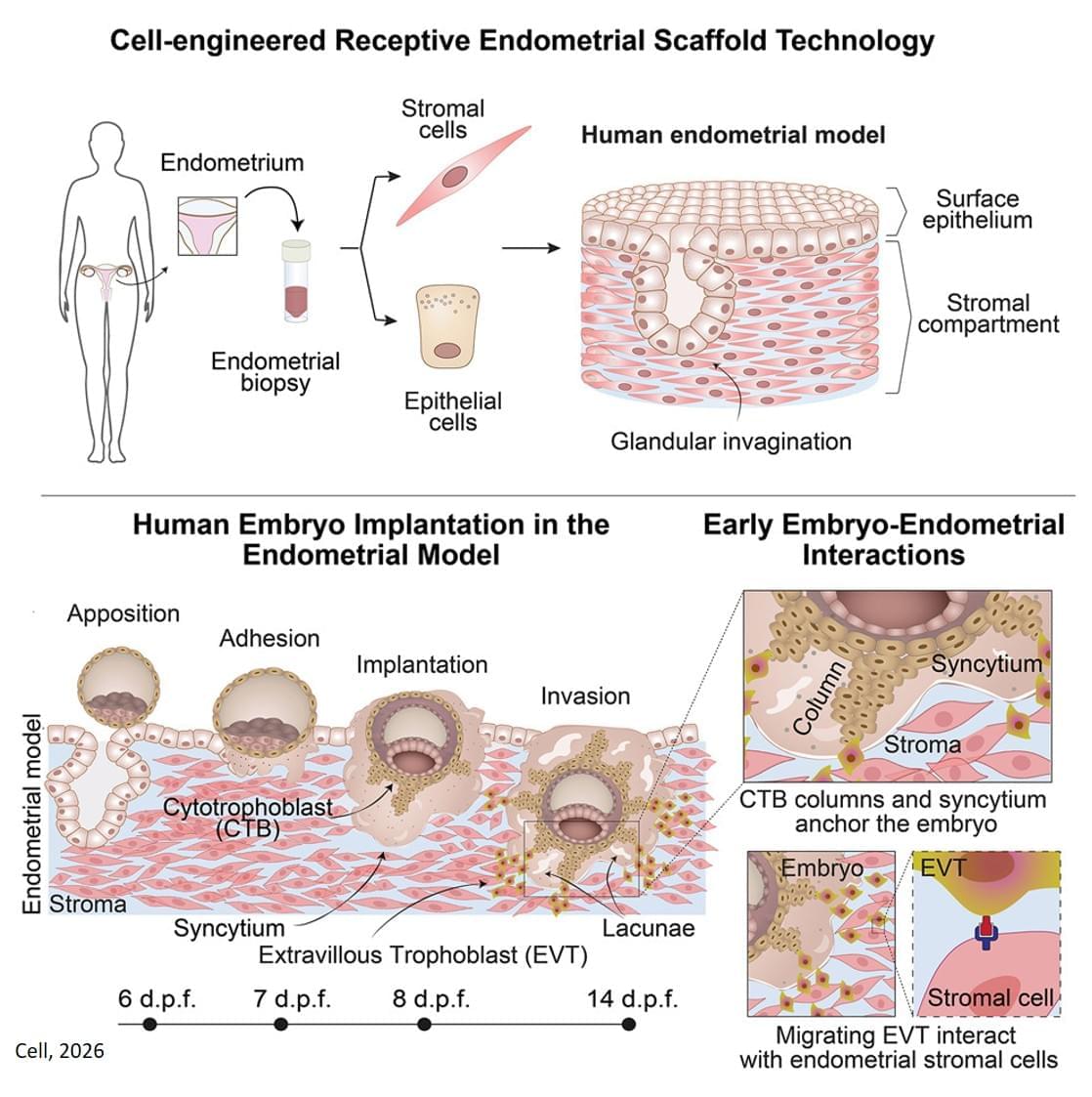

The new 3D model system looks to replicate the complex physiological properties and cellular composition of the endometrium. The model is built in a step-by-step process by bringing together the different components of endometrial tissue. The team isolated two essential cell types that form endometrial tissue – epithelial cells and stromal cells – from tissue donated by healthy people who had endometrial biopsies.

As well as the cell types, the researchers sought to recreate the structure of the womb lining. Information from donated endometrial tissue was used to identify the tissue components that give the womb lining its structure. The researchers were able to incorporate these components together with the stromal cells into a special type of gel to support the growth of the cells in a thick layer. On top of this, they added the epithelial cells, which spread out over the surface of the stromal cells.

Once assembled, this formed an advanced replica of the womb lining, matching a biopsy of endometrial tissue in terms of cellular architecture, and showing responses to hormone stimulation that indicate the engineered womb lining’s receptivity for embryo implantation.

The team tested their model using donated early-stage human embryos from IVF procedures, and found that the embryo – at this point a compact ball of cells – underwent the expected stages expected of adhesion and invasion into the endometrial scaffold. Following implantation, the embryos increased secretion of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), a biochemical marker used in pregnancy tests to confirm pregnancy, and other pregnancy-associated proteins.

Furthermore, the system supported post-implantation development of the embryo, enabling the analysis of embryo stages (12−14 days post fertilisation) that have been largely unexplored. The researchers observed that implanted embryos reached several developmental milestones, such as the appearance of specialist cell types in the embryo and also the establishment of precursor cell types important for the development of the placenta.

Using single cell analysis of implantation sites, the researchers were able to profile cells at the interface between the embryo and endometrium model, effectively listening in to the molecular communication between the tissues. Their results provide new insight into the complex interactions between the embryo and endometrial environment that underpin embryo development immediately after implantation.