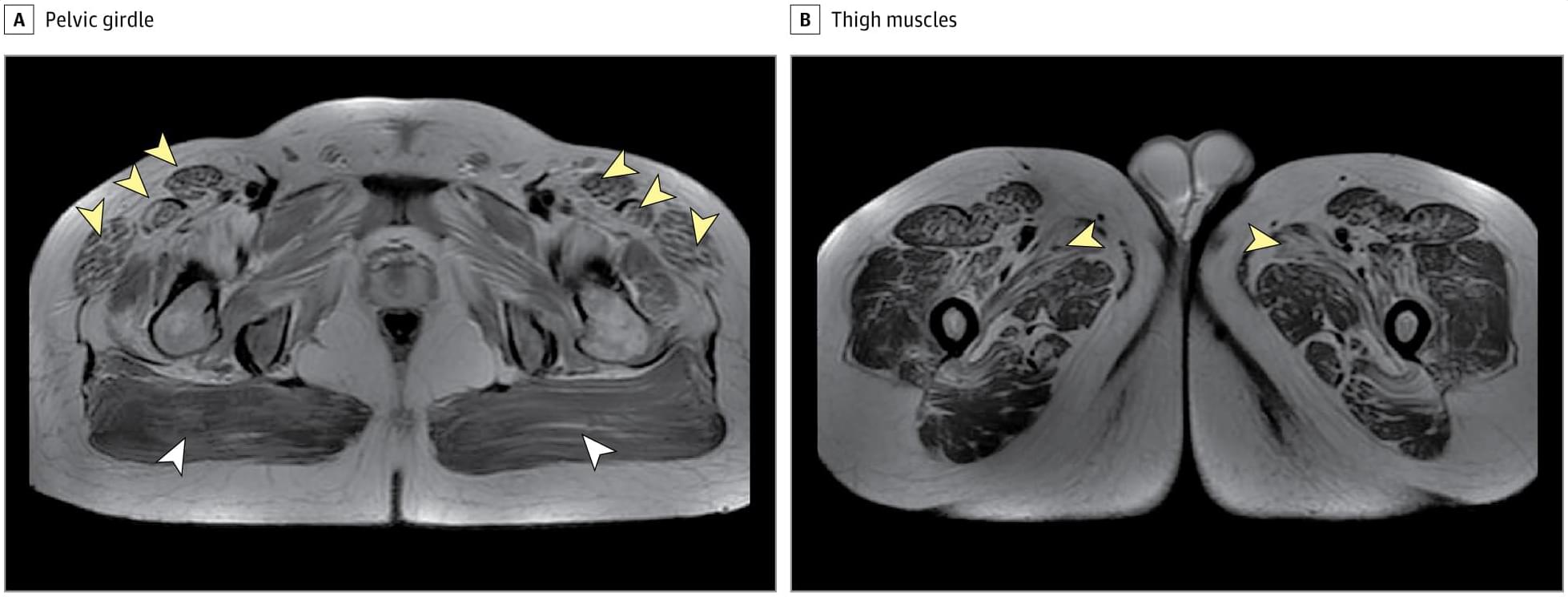

This case report describes a patient with X-linked FHL1-related myofibrillar myopathy and Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 1A, a dual pathology revealed by imaging and genetic testing.

Dopamine is a member of a class of molecules called the catecholamines, which serve as neurotransmitters and hormones. In the brain, dopamine serves as a neurotransmitter and is released from nerve cells to send signals to other nerves. Outside of the nervous system, it acts as a local chemical messenger in several parts of the body.

Image Copyright: Meletios, Image ID: 71,648,629 via shutterstock.com

A number of important neurodegenerative diseases are associated with abnormal function of the dopamine system and some of the main medications used to treat those illnesses work by changing the effects of dopamine. The condition Parkinson’s disease is caused by a loss of dopamine secreting cells in a brain area called the substantia nigra.

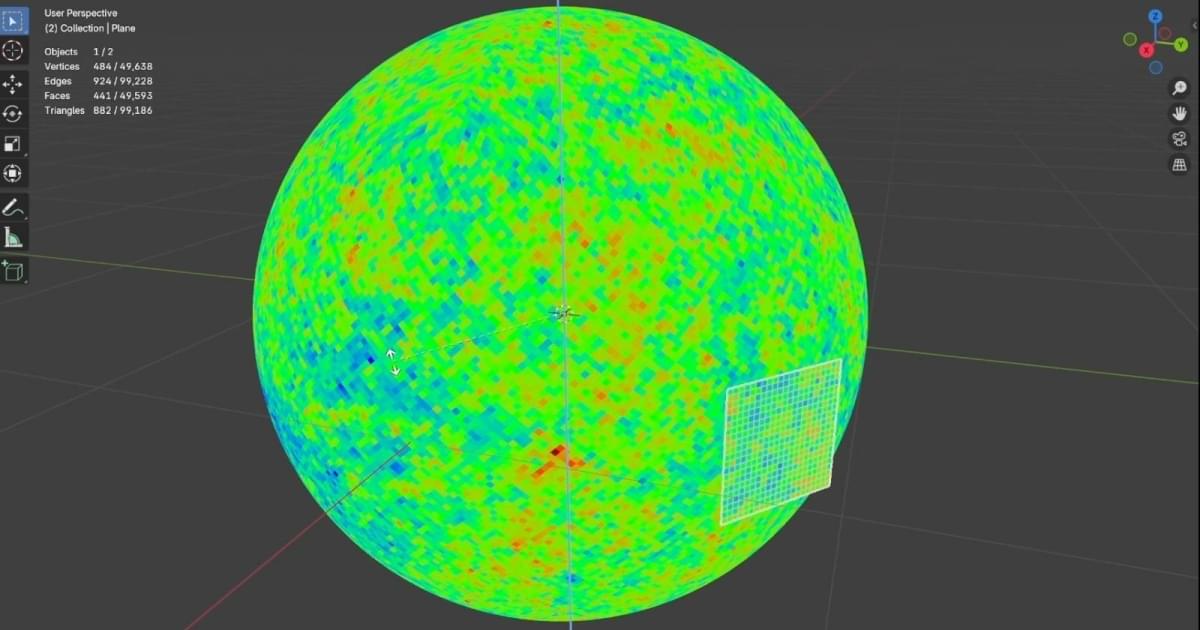

We recently shared the story of Blender’s role in the adult animated series Il Baracchino, and now, a fascinating new article by Ph.D. student MohammadHossein Jamshidi showcases how he applied Geometry Nodes in his cosmology research.

Cosmology is the study of the universe and its fundamental nature. MohammadHossein Jamshidi, from Shahid Beheshti University in Iran, has also worked as an animation engineer in the game industry since 2012. His initial inspiration to apply Blender to scientific work came from the creative projects of Seanterelle, which led him to experiment with using Geometry Nodes for cosmological computations.

In the article, he shares several ideas and techniques for using Blender in his research, and he believes that these approaches could be applied to other areas of science as well. All the files featured are freely available on this GitHub repository.

Developer Puck released the Pixelizer tool to add retro aesthetics to your 3D props.

A paper describing Hopp’s upcoming study published on the CureAlz website, titled, “How Do Microglia Contribute to the Spread of Tau Pathology in Alzheimer’s Disease?”, says that while tau aggregates are a defining feature of Alzheimer’s disease and closely track with brain cell loss, memory problems and cognitive decline, much still isn’t known about how it spreads or what role the brain’s immune system plays in the process.

There is evidence, it says, that toxic forms of tau, which have become “misfolded” or dysfunctional, act like a “bad influence.”

“When they encounter nearby healthy tau proteins, they cause them to misfold as well, triggering a chain reaction that spreads from one brain region to another,” according to the paper. “Microglia … are among the first to encounter these toxic tau ‘seeds.’ Normally, microglia protect the brain by clearing debris and helping repair damage. But growing evidence suggests that microglia may also contribute to tau’s spread by engulfing misfolded tau and inadvertently releasing it, thereby amplifying its harmful effects.”

A researcher with the Glenn Biggs Institute for Alzheimer’s and Neurodegenerative Diseases at UT Health San Antonio has received a two-year, $402,500 grant award from the Cure Alzheimer’s Fund to study how microglia, the brain’s resident immune cells, paradoxically might contribute to the spread of toxic forms of tau protein in the disease.

Sarah C. Hopp, PhD, associate professor of pharmacology with the Biggs Institute and the South Texas Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center, along with her lab have been instrumental in uncovering the behavior of microglia. UT Health San Antonio is the academic health center of The University of Texas at San Antonio.

Starting this month, Hopp’s lab will test the hypothesis that microglial uptake of tau is a key mechanism driving its spread through the brain, and that specific molecular pathways determine whether this process protects or harms neurons. The Cure Alzheimer’s Fund, also known as CureAlz, is a nonprofit organization that funds research “with the highest probability of preventing, slowing or reversing Alzheimer’s disease.”

While 2026 has been an objectively terrible year for humans thus far, it’s turning out—for better or worse—to be a banner year for robots. (Robots that are not Tesla’s Optimus thingamajig, anyway.) And it’s worth thinking about exactly how remarkable it is that the new humanoid robots are able to replicate the smooth, fluid, organic movements of humans and other animals, because the majority of robots do not move like this.

Take, for example, the robot arms used in factories and CNC machines: they glide effortlessly from point to point, moving with both speed and exquisite precision, but no one would ever mistake one of these arms for that of a living being. If anything, the movements are too perfect. This is at least partly due to the way these machines are designed and built: they use the same ideas, components, and principles that have characterised everything from the water wheel to the combustion engine.

But that’s not how living creatures work. While the overwhelming majority of macroscopic living beings contain some sort of “hard” parts—bones or exoskeletons—our movements are driven by muscles and ligaments that are relatively soft and elastic.

Researchers developed DeepRare, an LLM-driven multi-agent diagnostic system that integrates clinical descriptions, phenotype data, and genomic information to improve rare disease identification. Across thousands of cases, the system showed higher diagnostic recall than existing AI tools and clinicians in benchmark testing, while providing traceable reasoning linked to medical evidence.

Every major AI company has the same safety plan: when AI gets crazy powerful and really dangerous, they’ll use the AI itself to figure out how to make AI safe and beneficial. It sounds circular, almost satirical. But is it actually a bad plan? Today’s guest, Ajeya Cotra, recently placed 3rd out of 413 participants forecasting AI developments and is among the most thoughtful and respected commentators on where the technology is going.

She thinks there’s a meaningful chance we’ll see as much change in the next 23 years as humanity faced in the last 10,000, thanks to the arrival of artificial general intelligence. Ajeya doesn’t reach this conclusion lightly: she’s had a ring-side seat to the growth of all the major AI companies for 10 years — first as a researcher and grantmaker for technical AI safety at Coefficient Giving (formerly known as Open Philanthropy), and now as a member of technical staff at METR.

So host Rob Wiblin asked her: is this plan to use AI to save us from AI a reasonable one?

Ajeya agrees that humanity has repeatedly used technologies that create new problems to help solve those problems. After all:

• Cars enabled carjackings and drive-by shootings, but also faster police pursuits.

• Microbiology enabled bioweapons, but also faster vaccine development.

• The internet allowed lies to disseminate faster, but had exactly the same impact for fact checks.

But she also thinks this will be a much harder case. In her view, the window between AI automating AI research and the arrival of uncontrollably powerful superintelligence could be quite brief — perhaps a year or less. In that narrow window, we’d need to redirect enormous amounts of AI labour away from making AI smarter and towards alignment research, biodefence, cyberdefence, adapting our political structures, and improving our collective decision-making.

The plan might fail just because the idea is flawed at conception: it does sound a bit crazy to use an AI you don’t trust to make sure that same AI benefits humanity.

Researchers at the University of Seville have analyzed alterations in the cerebral cortex in people suffering from psychosis. Their findings show that psychosis does not follow a single trajectory, but rather its evolution depends on a complex interaction between brain development, symptoms, cognition and treatment. The authors therefore emphasize the need to adopt more personalized approaches that take individual differences into account in order to better understand the disease and optimize long-term therapeutic strategies.

Psychosis is a set of symptoms—such as hallucinations and delusions—that are common in schizophrenia and involve a loss of contact with reality. From their first manifestation, known as the first psychotic episode, these symptoms can appear and evolve in very different ways between individuals, thus making schizophrenia a particularly complex disorder.

The results of the study show that, at the time of the first episode, people with psychosis present a reduction in cortical volume, which is particularly marked in regions with a high density of serotonin and dopamine receptors, key neurotransmitters in both the pathophysiology of psychosis and the mechanism of action of antipsychotics. The data also suggest that both neurons and other brain cells involved in inflammatory and immunological processes may play an important role in the disease.