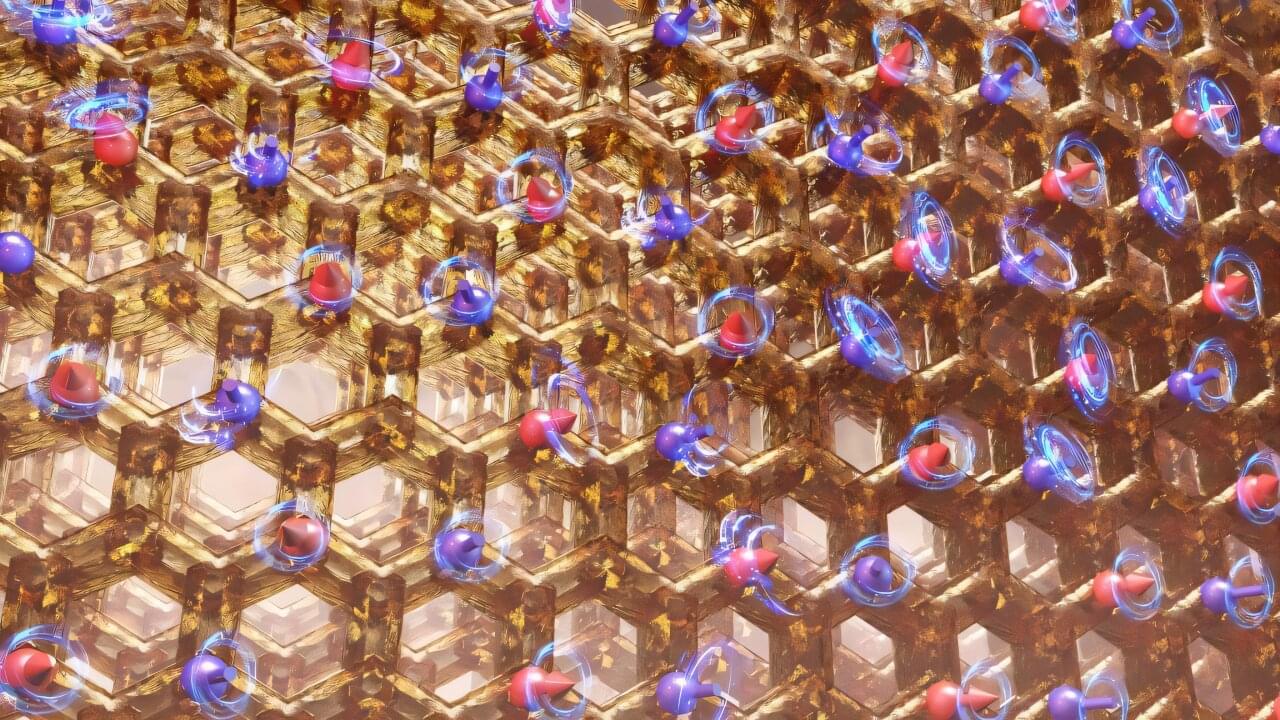

Researchers at the Department of Energy’s Oak Ridge National Laboratory are pioneering the design and synthesis of quantum materials, which are central to discovery science involving synergies with quantum computation. These innovative materials, including magnetic compounds with honeycomb-patterned lattices, have the potential to host states of matter with exotic behavior.

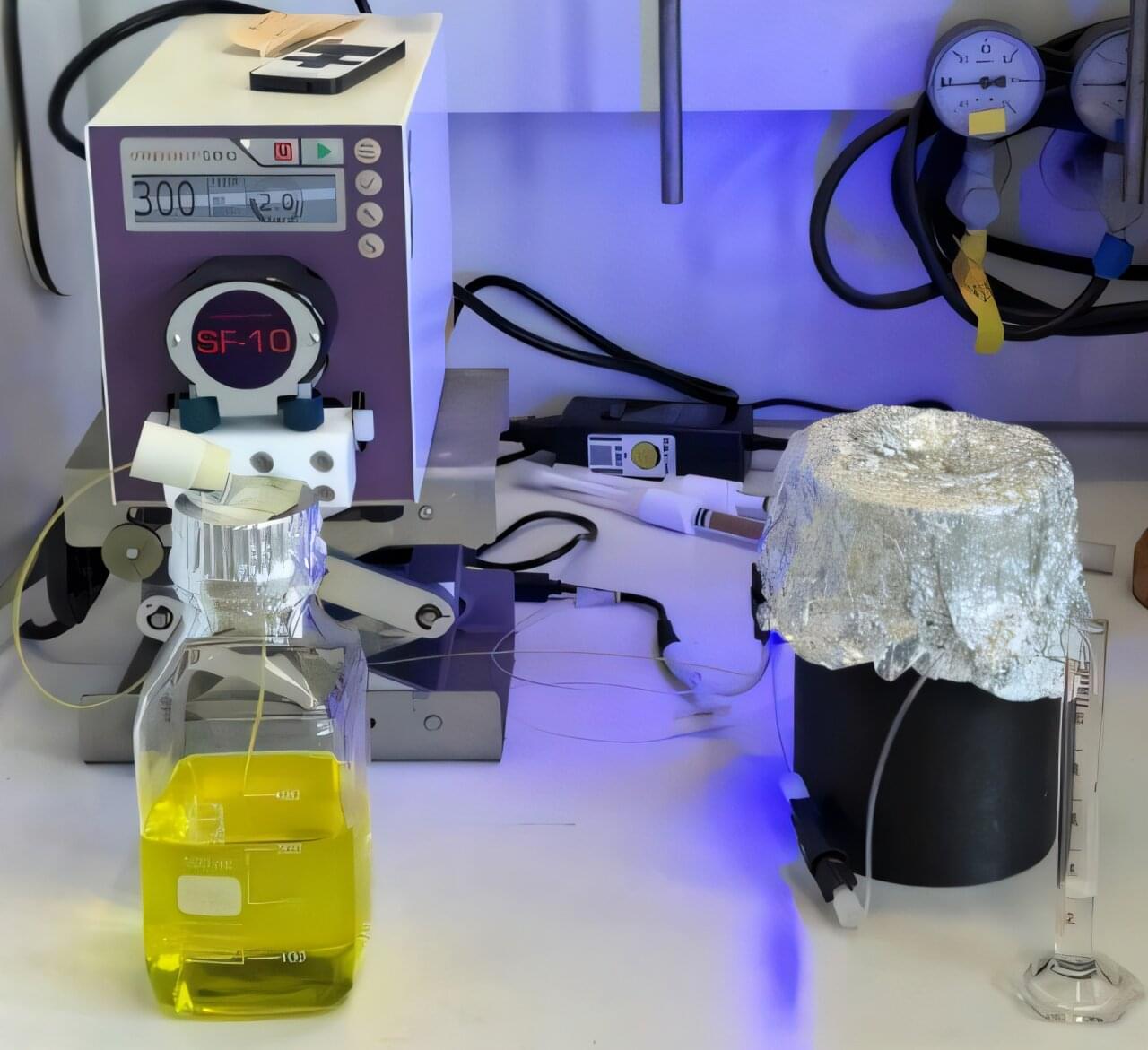

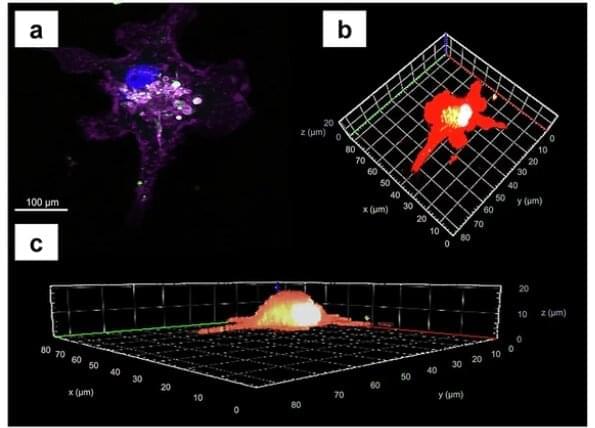

Using theory, experimentation and computation, scientists synthesized a magnetic honeycomb of potassium cobalt arsenate and conducted the most detailed characterization of the material to date. They discovered that its honeycomb structure is slightly distorted, causing magnetic spins of charged cobalt atoms to strongly couple and align.

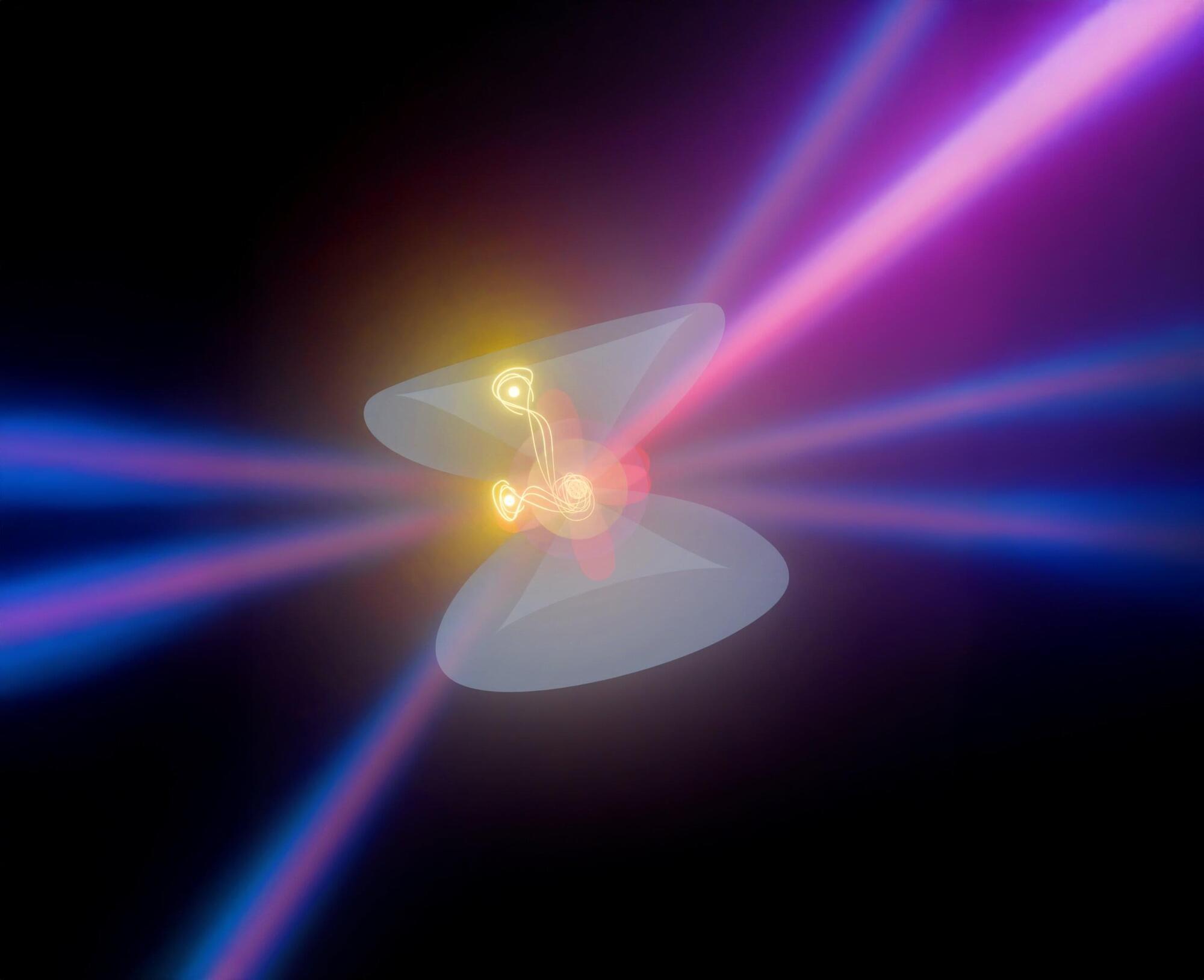

Tuning these interactions, such as through chemically modifying the material or applying a large magnetic field, may enable the formation of a state of matter known as a quantum spin liquid. Unlike permanent magnets, in which spins align fixedly, quantum spins do not freeze in one magnetic state.