Read “” by Myk Eff on Medium.

When a patient in a clinical trial experiences genuine pain relief from an inert sugar pill, something remarkable occurs that contemporary medicine awkwardly labels the placebo effect — a term that simultaneously acknowledges the phenomenon while dismissing it as mere illusion. Yet what if this dismissal represents not scientific rigor but ontological timidity? What if the placebo effect, rather than being a confounding variable to be controlled away, is actually nature’s clearest demonstration of a quantum interface between consciousness and physiology, hiding in plain sight within the very architecture of our clinical trials? The question is not whether belief heals, but what belief actually is when we take seriously the contemporary understanding that information itself possesses physical reality.

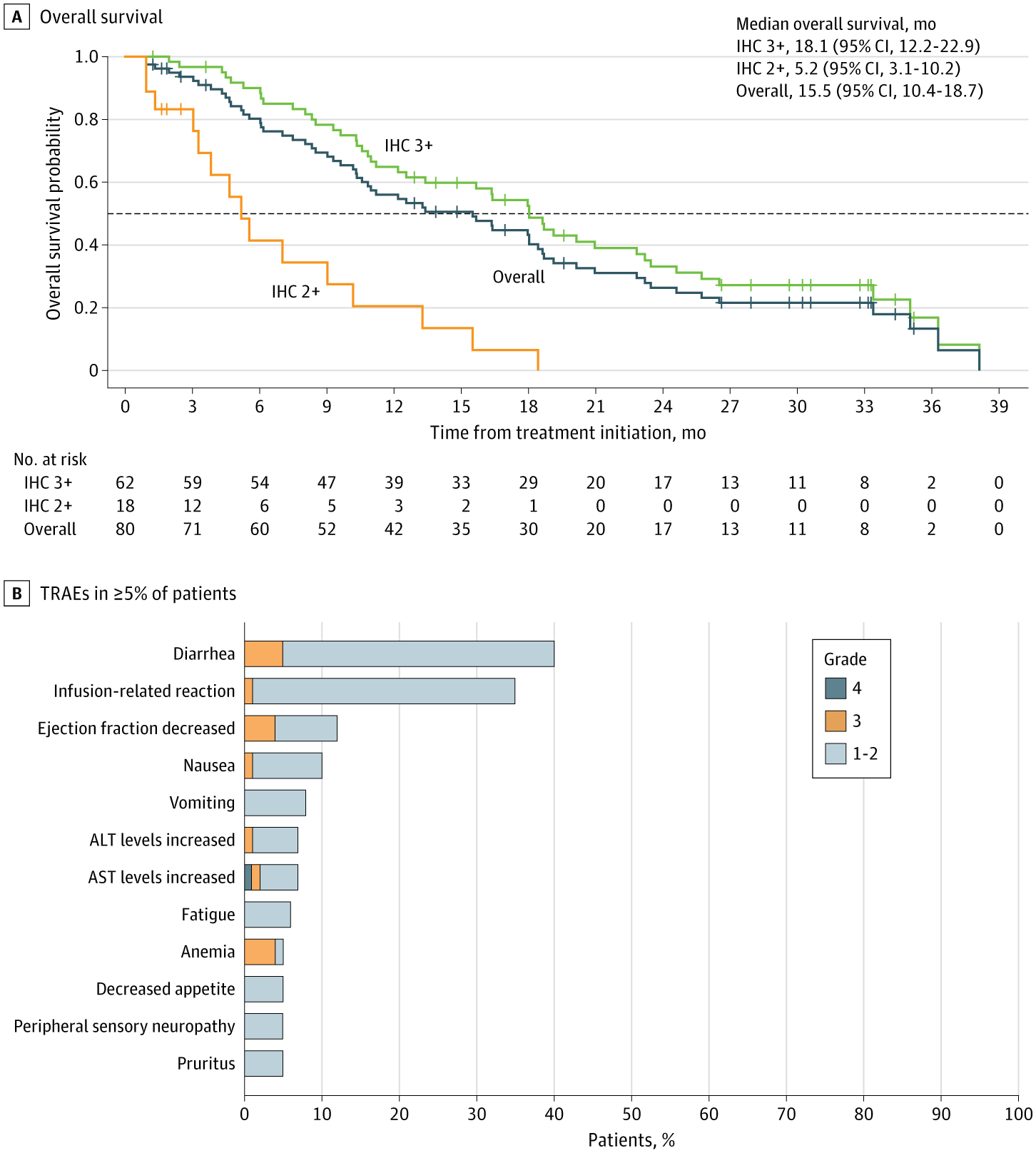

The empirical robustness of placebo effects has become impossible to ignore. In their comprehensive meta-analysis published in The Lancet, Hróbjartsson and Gøtzsche (2001) examined 114 clinical trials and found that while placebo effects vary considerably across conditions, they demonstrate genuine clinical significance in pain reduction, with effect sizes rivaling those of established pharmaceutical interventions. More provocatively, Benedetti’s research on placebo analgesia has revealed that the effect operates through identifiable neurochemical pathways — placebo-induced pain relief can be blocked by naloxone, an opioid antagonist, demonstrating that the patient’s belief literally triggers the release of endogenous opioids (Benedetti, Mayberg, Wager, Stohler, & Zubieta, 2005). This is not imagination overriding reality; this is imagination as a physical force, translating expectation into molecular cascade.

Yet the standard neurobiological explanation, while accurate, remains curiously incomplete. Yes, belief activates specific neural circuits; yes, these circuits trigger biochemical responses; yes, measurable physiological changes occur. But this mechanistic account merely pushes the mystery one level deeper. How does the abstract informational content of a belief — the semantic meaning this pill will relieve my pain — couple to the physical substrate of neurons and neurotransmitters? The conventional answer invokes learning, conditioning, and expectation, but these terms describe the phenomenon without explaining the fundamental ontological transition from meaning to matter, from information to effect.