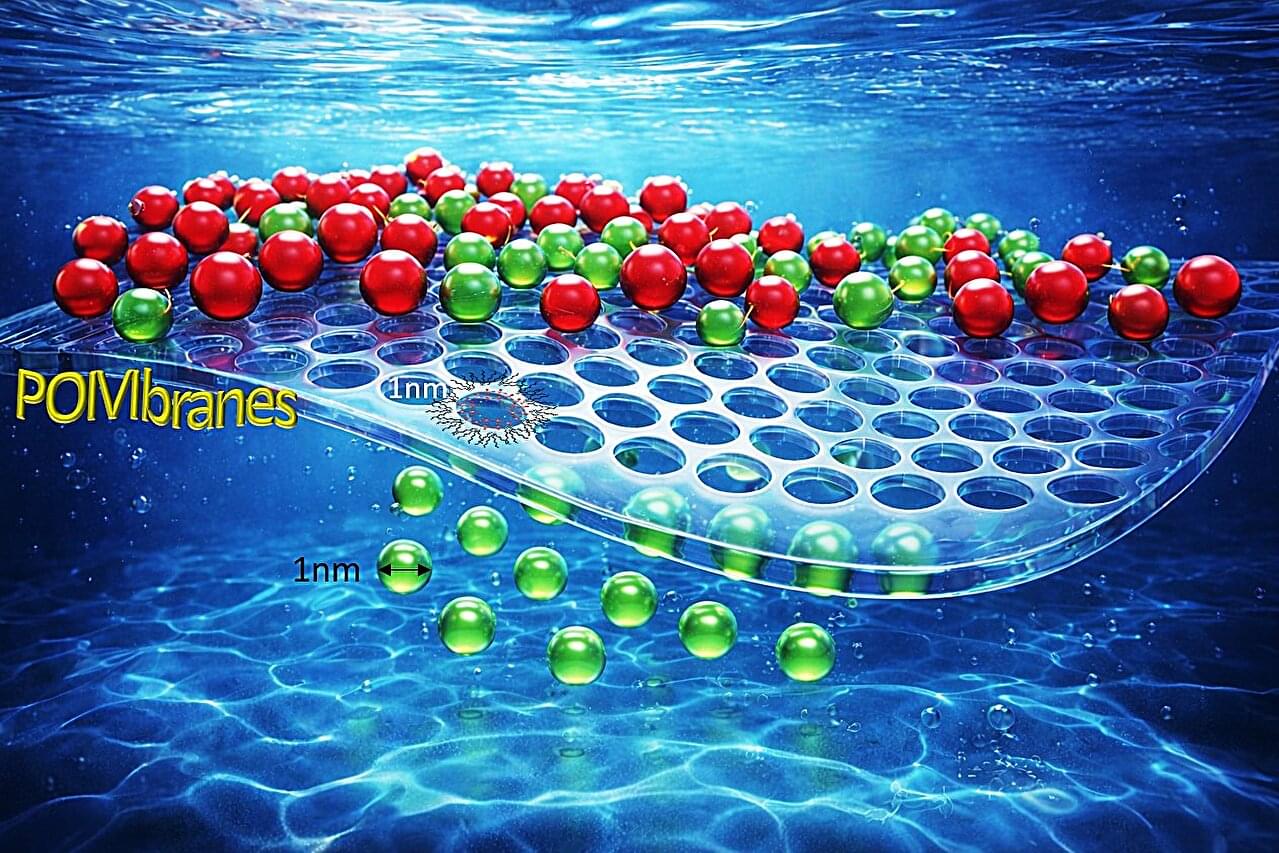

Scientists have collaborated to develop a new class of highly precise filtration membranes. The research, published in the Journal of the American Chemical Society, could significantly reduce energy consumption and enable large-scale water reuse in industry. The team includes researchers from the CSIR-Central Salt and Marine Chemicals Research Institute (CSMCRI), Indian Institute of Technology Gandhinagar, the Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, and the S N Bose National Centre for Basic Sciences.

Everyday industrial processes, like purifying medicines, cleaning textile dyes, and processing food, rely on “separations.” Currently, these processes are incredibly energy-hungry, accounting for nearly 40% to 50% of all global industrial energy use. Most factories still use old-fashioned methods like distillation and evaporation to separate ingredients, which are expensive and leave a heavy carbon footprint.

Although membrane-based technologies are considered cleaner, most polymer membranes currently used in industry have irregularly sized pores that tend to degrade over time, limiting their effectiveness. Thus, they lack the precision and long-term stability needed for demanding industrial applications.