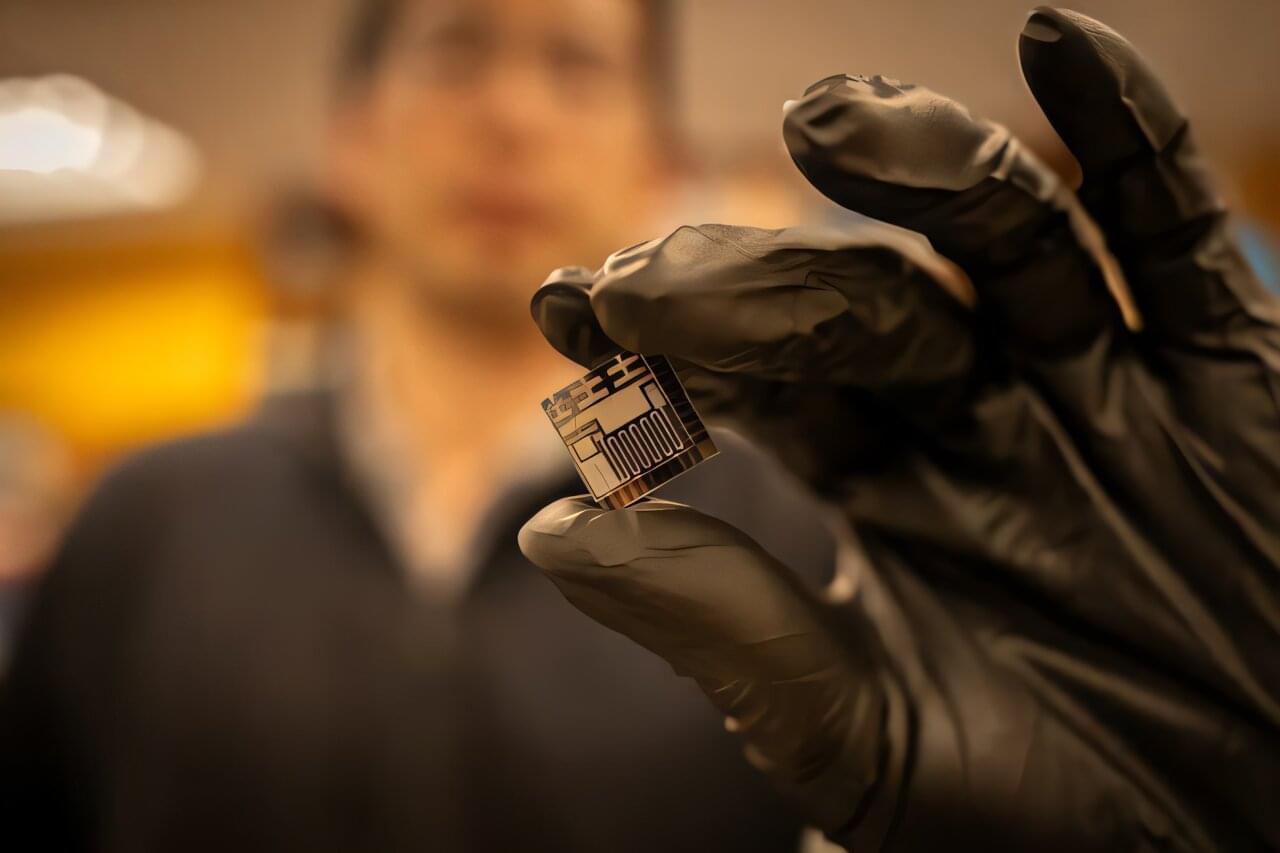

A new microscale gas chromatography system integrates all fluidic components into a single chip for the first time. The design leverages three Knudsen pumps that move gas molecules using heat differentials to eliminate the need for valves, according to a new University of Michigan Engineering study published in Microsystems & Nanoengineering. The monolithic gas sampling and analysis system, or monoGSA system for short, could offer reliable, low-cost monitoring for industrial chemical or pharmaceutical synthesis, natural gas pipelines, or even at-home air quality.

Gas chromatography has long been considered the gold standard for measuring and quantifying volatile organic compounds—gases emitted from industrial processes, fuels, household products and more. Recently, micro gas chromatography miniaturized the technology to briefcase-size or smaller, bringing gas analysis from the laboratory to the source.

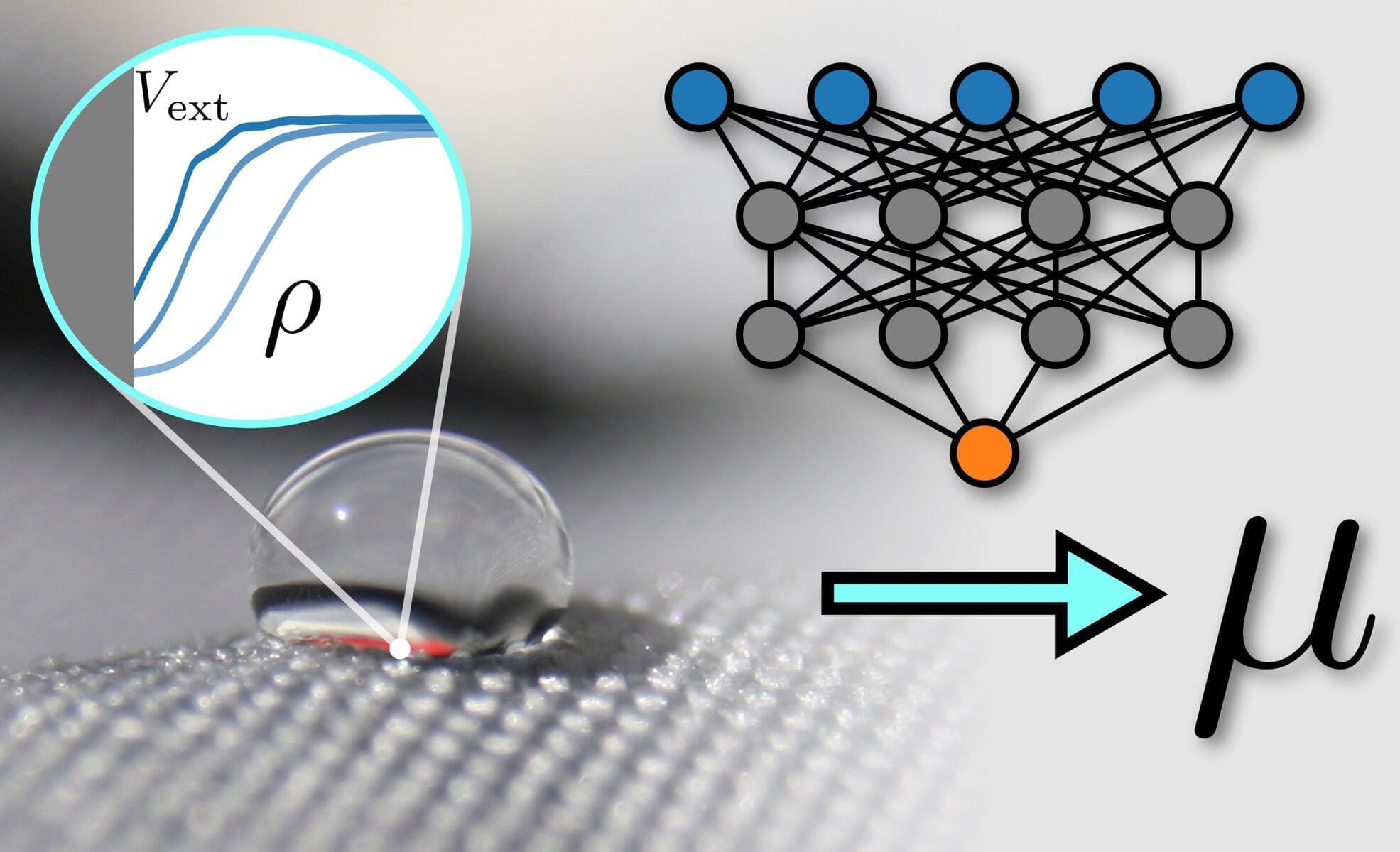

Most micro gas chromatography systems use pumps and valves to move gas molecules from an input port to a preconcentrator, which extracts and concentrates samples, then from the preconcentrator to a column for chemical separation, and then to the detector and finally to an exhaust port. Up to this point, pumps and valves have been fabricated and assembled separately, which increases device size, assembly cost and risk of failure at connection points.