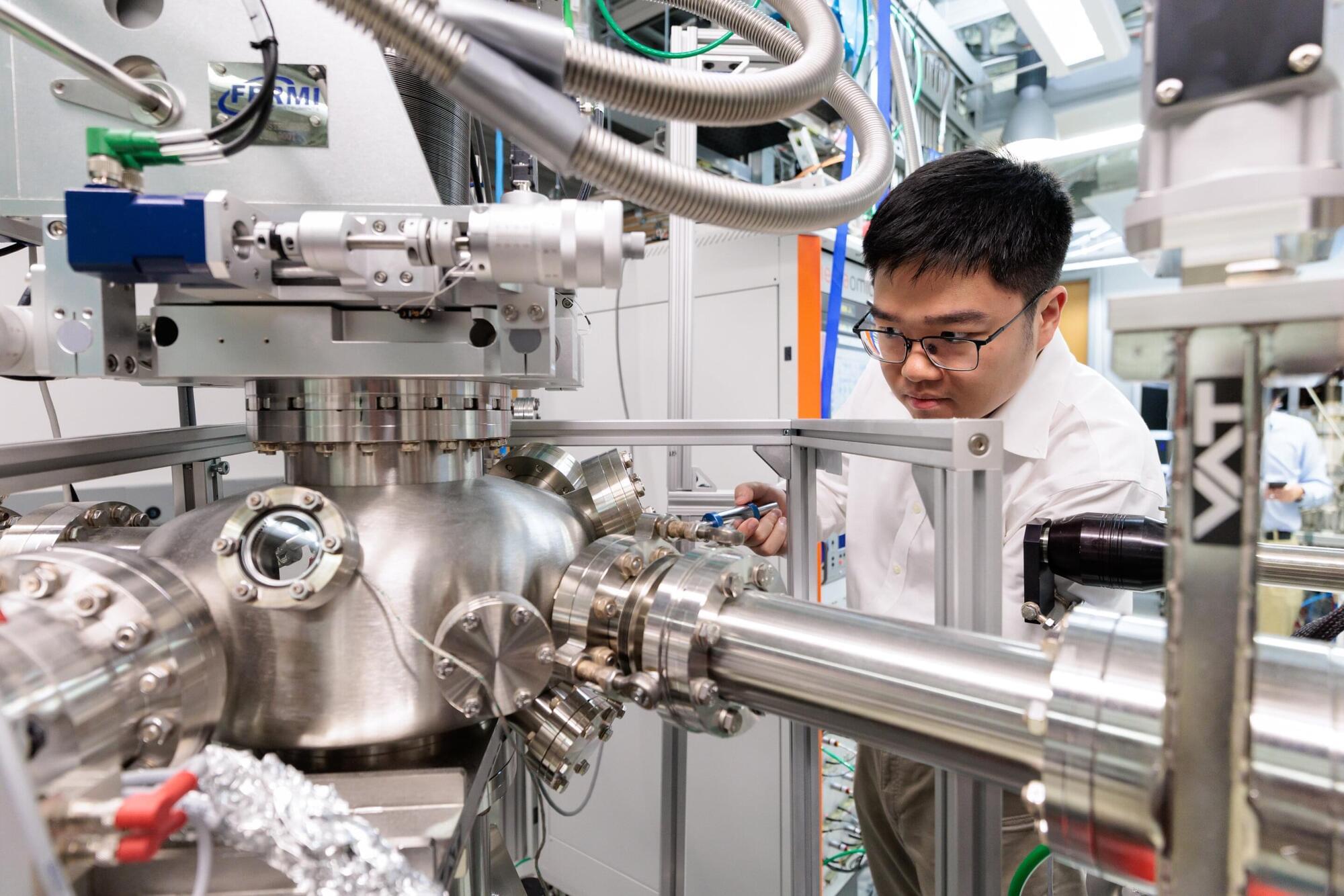

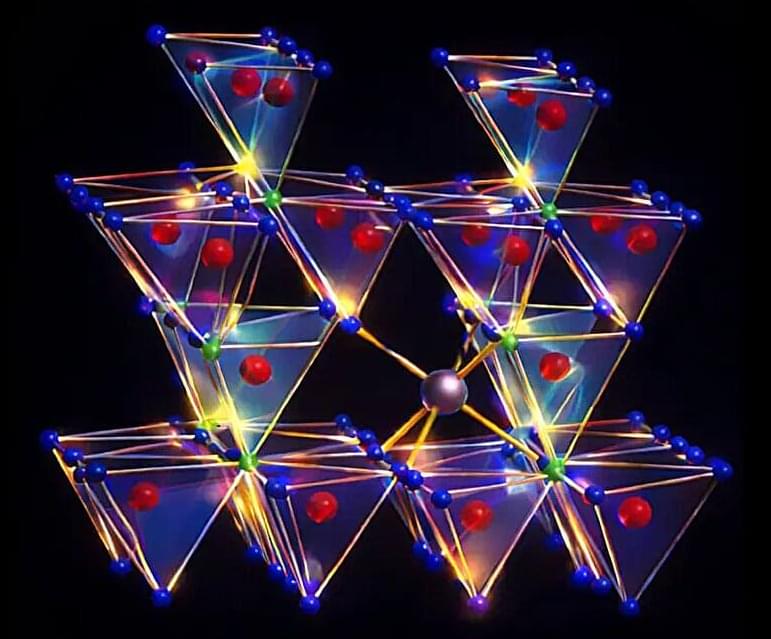

Today’s most powerful computers hit a wall when tackling certain problems, from designing new drugs to cracking encryption codes. Error-free quantum computers promise to overcome those challenges, but building them requires materials with exotic properties of topological superconductors that are incredibly difficult to produce. Now, researchers at the University of Chicago Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering (UChicago PME) and West Virginia University have found a way to tune these materials into existence by simply tweaking a chemical recipe, resulting in a change in many-electron interactions.

The team adjusted the ratio of two elements— tellurium and selenium —that are grown in ultra-thin films. By doing so, they found they could switch the material between different quantum phases, including a highly desirable state called a topological superconductor.

The findings, published in Nature Communications, reveal that as the ratio of tellurium and selenium changes, so too do the correlations between different electrons in the material—how strongly each electron is influenced by those around it. This can serve as a sensitive control knob for engineering exotic quantum phases.