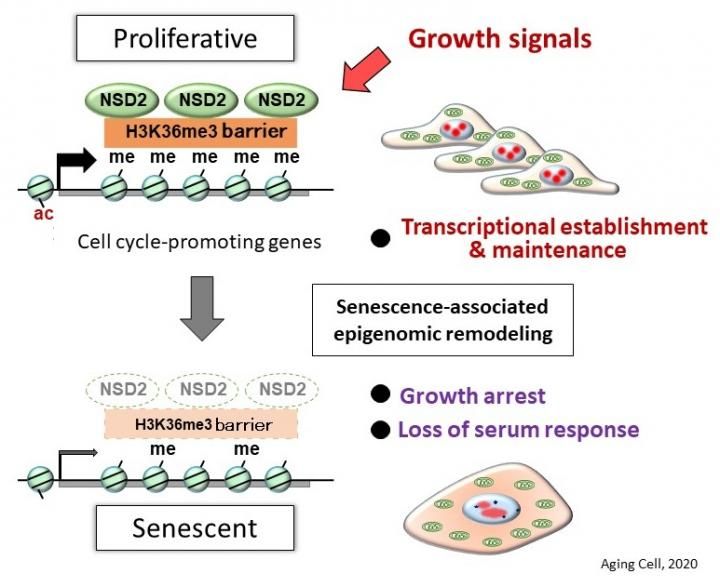

NSD2 is the fourth protective factor of cellular senescence that our team has identified,” said Professor Mitsuyoshi Nakao. “With the discovery that NSD2 protects against cellular senescence, this study clarifies a basic mechanism of aging.

Researchers from Kumamoto University in Japan have used comprehensive genetic analysis to find that the enzyme NSD2, which is known to regulate the actions of many genes, also works to block cell aging. Their experiments revealed 1) inhibition of NSD2 function in normal cells leads to rapid senescence and 2) that there is a marked decrease in the amount of NSD2 in senescent cells. The researchers believe their findings will help clarify the mechanisms of aging, the development of control methods for maintaining NSD2 functionality, and age-related pathophysiology.

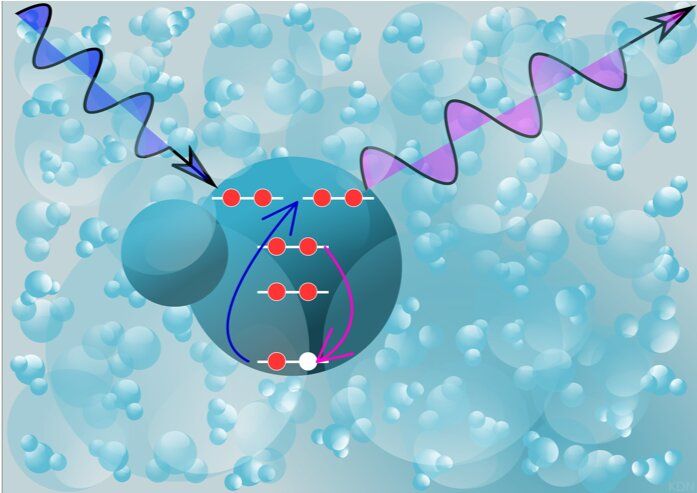

As the cells of the body continue to divide (cell reproduction), their function eventually declines and they stop growing. This cellular senescence is an important factor in health and longevity. Cell aging can also be stimulated when genomic DNA is damaged by physical stress, such as radiation or ultraviolet rays, or by chemical stress that occurs with certain drugs. However, the detailed mechanisms of aging are still unknown. Cell aging can be beneficial when a cell becomes cancerous; it prevents malignant changes by causing cellular senescence. On the other hand, it makes many diseases more likely with age. It is therefore important that cell aging is properly controlled.

Although senescent cells lose their proliferative ability, it has recently become clear that senescent cells secrete various proteins that act on surrounding cells to promote chronic inflammation and cancer development. Since senescent cells are more active than expected, cellular aging is thought to be responsible for whole body aging. This idea has been supported by reports of systemic aging suppression in aged mice after removal of accumulated senescent cells. In other words, if you can control cell aging, you may be able to control the progression of aging throughout the body.