Wrap up for 2025.

Every year I compile what I think were some important contributions to longevity research. Here is my list for 2025!!

Find me on Twitter — / eleanorsheekey.

Support the channel.

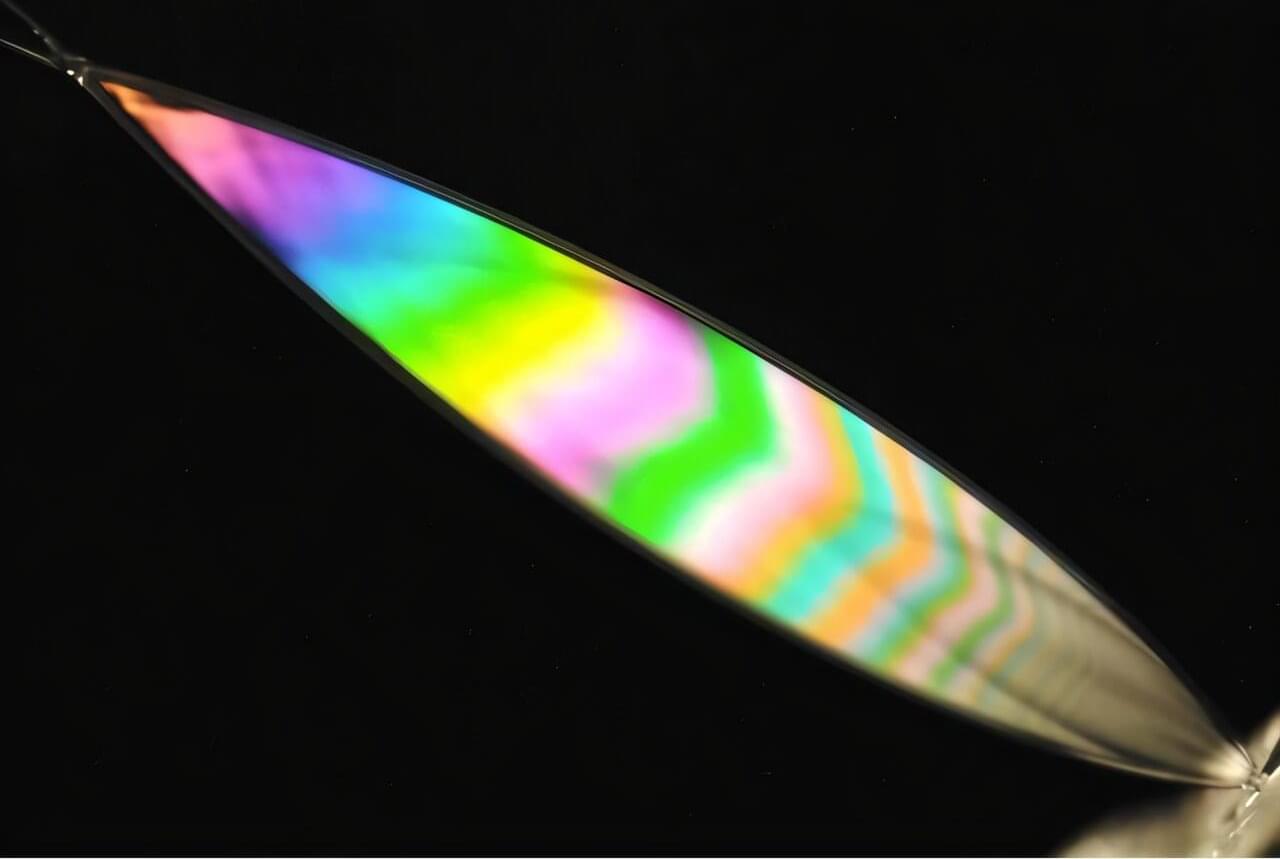

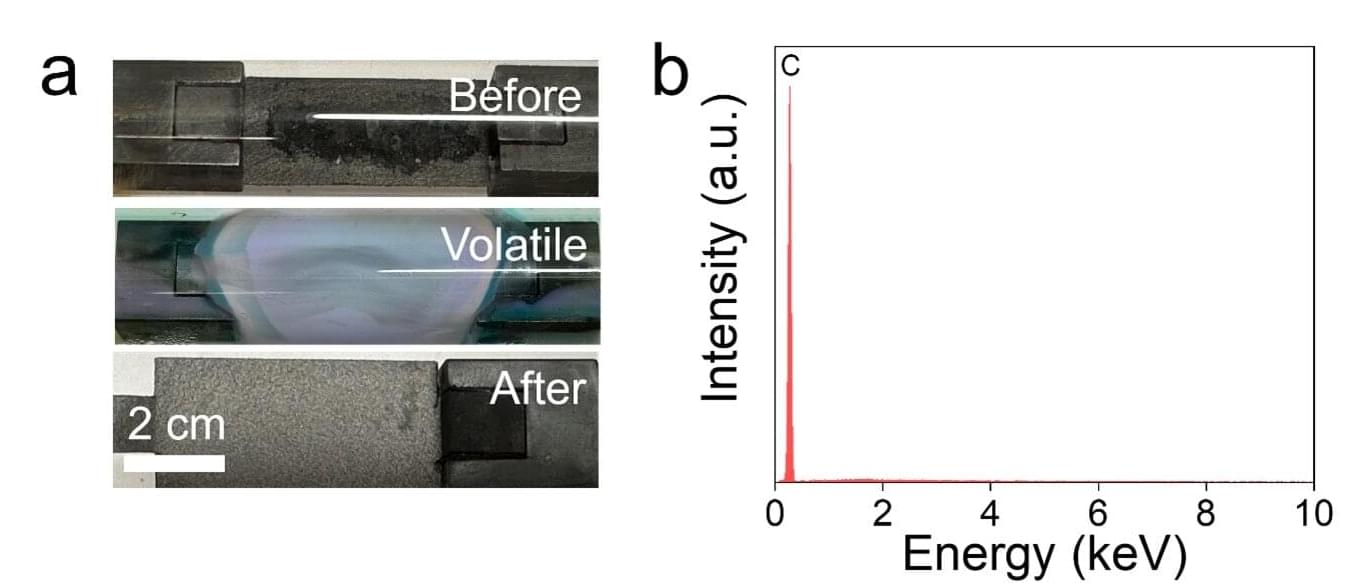

through PayPal — https://paypal.me/sheekeyscience?coun… through Patreon — / thesheekeyscienceshow TIMESTAMPS: 00:00 – Intro & “What is aging?” / Hallmarks 2025 02:07 – Cellular reprogramming 05:47 – Senescent cells 11:45 – GLP‑1 agonists & ITP 13:43 – Elastin fragments & ECM aging 15:22 – Cardiac ‘age‑switch’ experiment 16:18 – Systemic environment: FOXO3 cells, antler EVs, plasma exchange 19:26 – Things you wouldn’t have thought of: AI-predicted antibodies REFERENCES: What is aging / hallmarks Hallmarks of aging update 2025 (14 hallmarks, ECM + psychosocial isolation) https://www.sciencedirect.com/science… reprogramming Prevalent mesenchymal drift in aging and disease is reversed by partial reprogramming – Cell 2025 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2025.0… A single factor for safer cellular rejuvenation (SB000) – bioRxiv 2025 https://doi.org/10.1101/2025.06.05.65… https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.11… OpenAI x Retro Biosciences: AI‑designed reprogramming factors https://openai.com/index/accelerating… Restoration of neuronal progenitors by partial reprogramming in the aged neurogenic niche – Nature Aging 2024 (YouthBio’s scientific basis) https://doi.org/10.1038/s43587-024-00… Chemical reprogramming ameliorates cellular hallmarks of aging and extends lifespan in Caenorhabditis elegans – EMBO Molecular Medicine 2025 https://doi.org/10.1038/s44321-025-00… https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles… Senescent cells An unbiased cell‑culture selection yields DNA aptamers as senescence‑specific reagents – Aging Cell 2025 https://doi.org/10.1111/acel.70245 Senolytic CAR T cells reverse senescence‑associated pathologies – Amor et al., Nature 2020 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-24… Anti‑uPAR CAR T cells reverse and prevent aging‑associated defects in intestinal regeneration and fitness – Nature Aging 2025 https://doi.org/10.1038/s43587-025-01… Rejuvenation of Senescent Cells, In Vitro and In Vivo, by Low‑Frequency Ultrasound – Aging Cell 2025 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles… Supplements, ITP & GLP‑1s Are GLP‑1s the first longevity drugs? – Nature Biotechnology 2025 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-025-02… GLP‑1 receptor agonists at the crossroads of metabolism and longevity – Nature Aging https://www.nature.com/articles/s4151… Extension of lifespan by epicatechin, halofuginone and mitoglitazone in male but not female UM‑HET3 mice – GeroScience 2025 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11357-025-01… https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40973… ECM, elastin & cardiac environment Elastin‑derived extracellular matrix fragments drive aging through innate immune activation – Nature Aging 2025 https://doi.org/10.1038/s43587-025-00… Sun, A.R., Ramli, M.F.H., Shen, X. et al. Hybrid hydrogel–extracellular matrix scaffolds identify biochemical and mechanical signatures of cardiac ageing. Nat. Mater. 24, 1489–1501 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41563-025-02… Systemic environment: stem cells, EVs, plasma Senescence‑resistant human mesenchymal progenitor cells counter aging in primates – Cell 2025 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2025.0… Attenuation of primate aging via systemic infusion of senescence‑resistant cells – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles… Extracellular vesicles from antler blastema progenitor cells reverse bone loss and mitigate aging‑related phenotypes – Nature Aging 2025 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles… Human clinical trial of plasmapheresis effects on biomarkers of aging – Aging Cell 2025 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles… “Things you wouldn’t think of” – AI antibodies Atomically accurate de novo design of antibodies with atomic precision – Baker Lab, Nature 2025 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09… Computational design of human antibodies targeting any antigen – https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2025.1… Please note that The Sheekey Science Show is distinct from Eleanor Sheekey’s teaching and research roles. The information provided in this show is not medical advice, nor should it be taken or applied as a replacement for medical advice. The Sheekey Science Show and guests assume no liability for the application of the information discussed. Icons in intro; “https://www.freepik.com/free-photos-v…“Background vector created by freepik — www.freepik.com.

through Patreon — / thesheekeyscienceshow.

TIMESTAMPS: