The study, published in Cell Metabolism, builds on previous research showing that some gliomas can be slowed down through the patient’s diet. If a patient isn’t consuming certain protein building blocks, called amino acids, then some tumors are unable to grow. However, other tumors can produce these amino acids for themselves, and can continue growing anyway. Until now, there was no easy way to tell which patients would benefit from dietary restrictions.

The digital twin’s ability to map metabolic activity in tumors also helped determine whether a drug that prevents tumors from producing a building block for replicating and repairing DNA would work, as some cells can obtain that molecule from their environments.

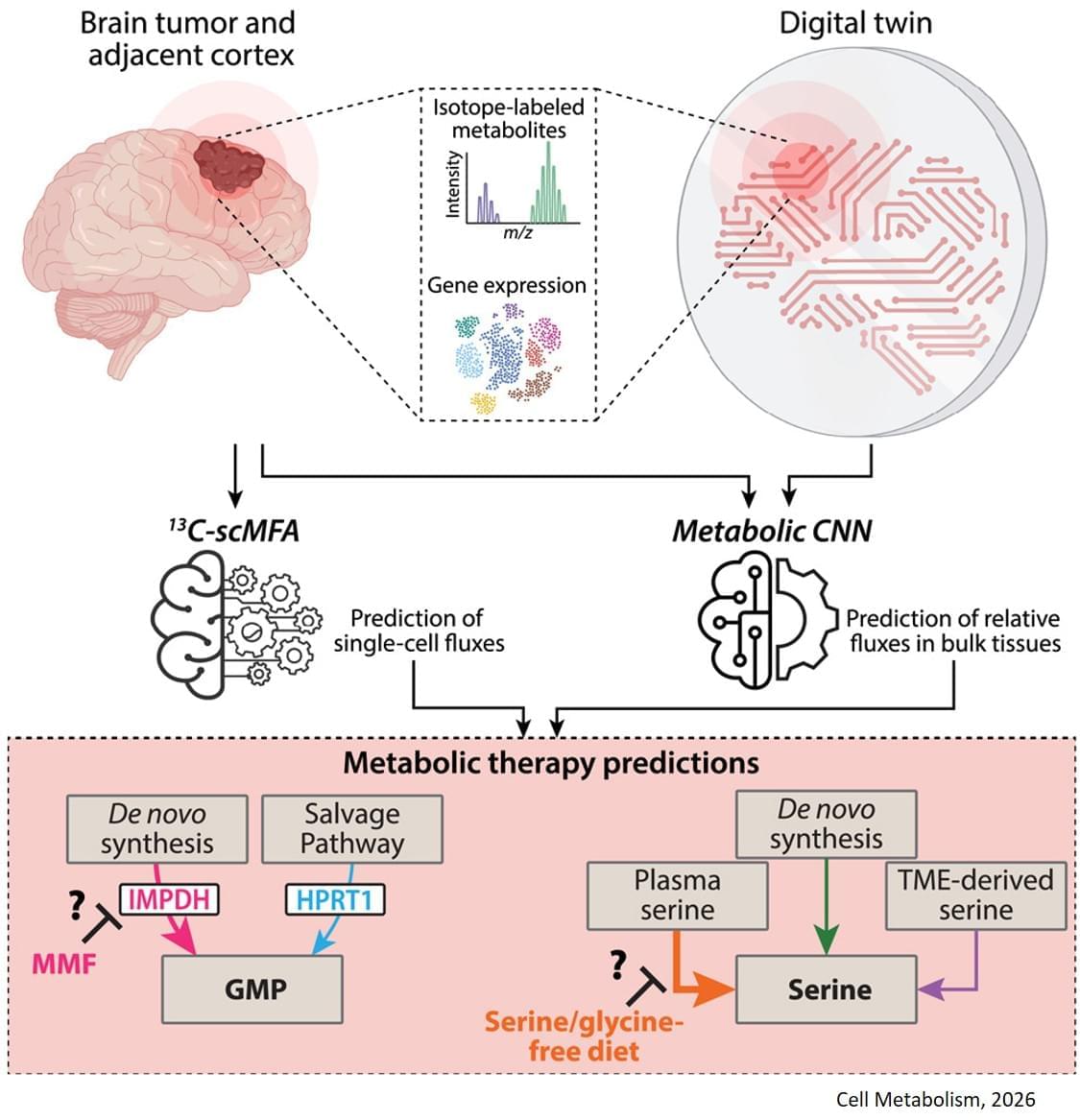

To overcome challenges in mapping tumor metabolism inside the brain, the team developed a computer-based “digital twin” that can predict how an individual patient’s brain tumor will react to each treatment.

“Typically, metabolic measurements during surgeries to remove tumors can’t provide a clear picture of tumor metabolism—surgeons can’t observe how metabolism varies with time, and labs are limited to studying tissues after surgery. By integrating limited patient data into a model based on fundamental biology, chemistry and physics, we overcame these obstacles,” said a co-corresponding author of the study.

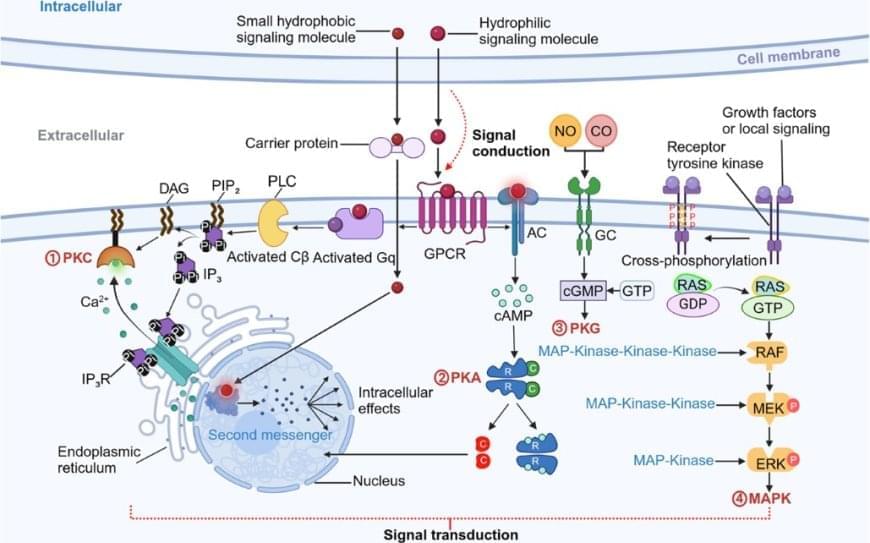

The digital twin uses patient data obtained through blood draws, metabolic measurements of the tumor tissue and the tumor’s genetic profile. The digital twin then calculates the speed at which the cancer cells consume and process nutrients, known as metabolic flux.

“This is the first time a machine learning and AI-based approach has been used to measure metabolic flux directly in patient tumors,” said a co-first author of the study.

The researchers built a type of deep learning model called a convolutional neural network and trained it on synthetic patient data, generated based on known biology and chemistry and constrained by measurements from eight patients with glioma who were infused with labeled glucose during surgery. By comparing their computer models with different data from six of those patients, they found the digital twins could predict metabolic activity with high accuracy. In experiments conducted on mice, the team confirmed that the diet only slowed tumor growth in mice that the digital twin had identified as good candidates for the treatment.