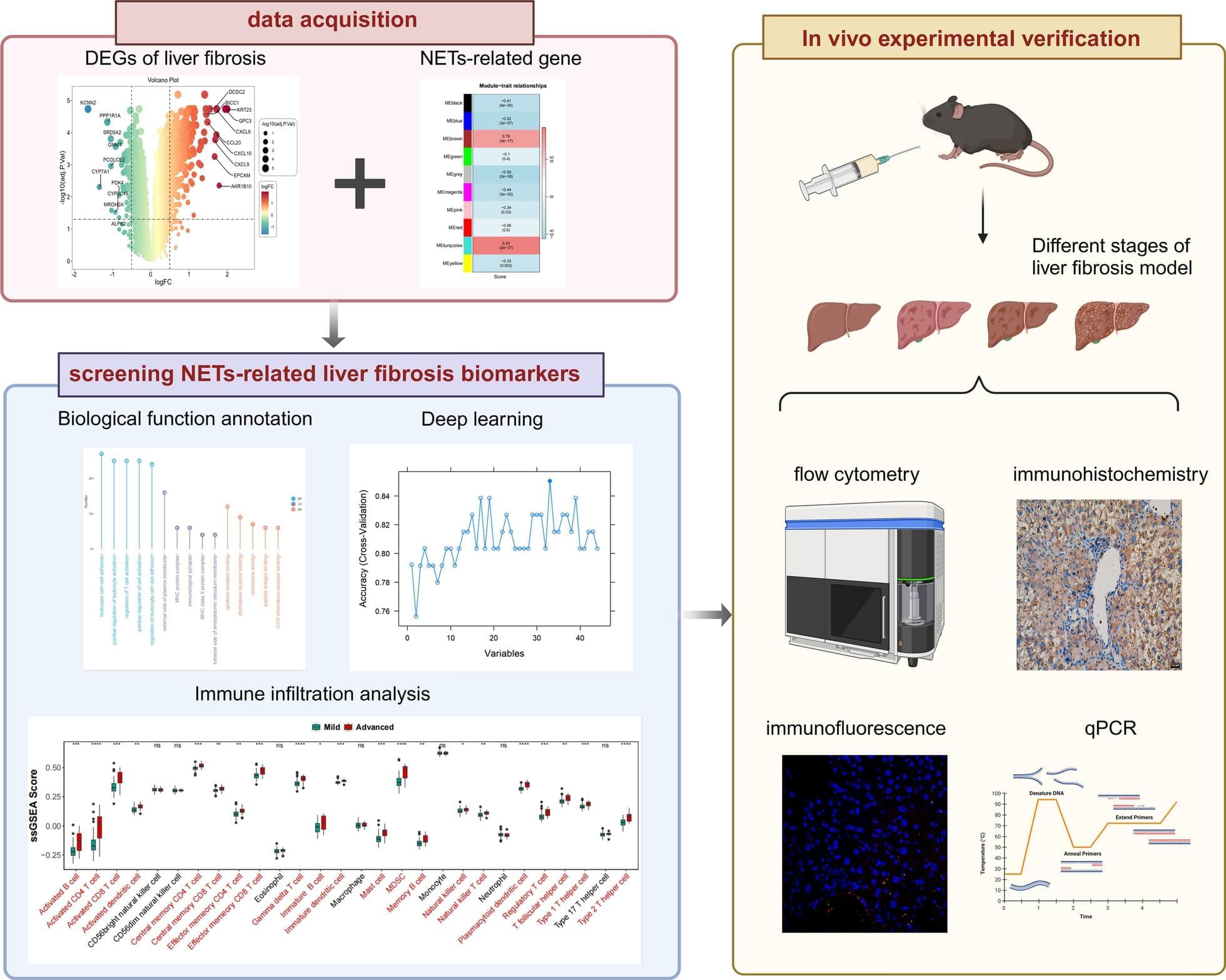

Combined metabolomics and transcriptomics analysis in eight different organs of tumor-bearing mice with and without cachexia allowed researchers to create metabolic signatures typical of cancer-associated weight loss. High-throughput analyses identified a cachexia-specific metabolic and genetic signature that provides insight into the progression of these metabolic changes.

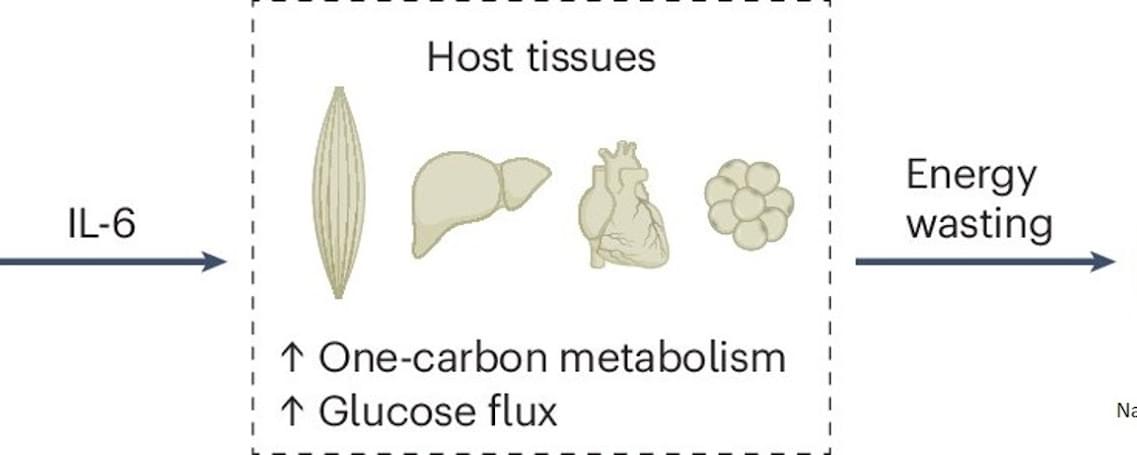

The researchers found that all organs showed increased activation of the so-called “one carbon cycle”, a biochemical process essential for the synthesis of nucleotides, amino acids, and cell regeneration. Products of this cycle, such as sarcosine or dimethylglycine, could potentially serve as biomarkers for cachexia in the future.

The study also revealed that hyperactivation of the one carbon cycle in muscle is associated with increased glucose metabolism (glucose hypermetabolism) and muscle atrophy. Early experiments suggest that inhibiting this process could prevent muscle loss. Comparative analyses across eight different mouse tumor models (lung, colon, and pancreatic cancer) confirmed that the one carbon signature represents a universal cachexia signature, independent of cancer type.

Currently, there is no approved drug for cancer cachexia in Germany. New approaches are being explored to address cancer-related appetite loss. This study provides the first evidence of how metabolism itself could potentially be normalized. Early experiments in cell cultures show that interventions targeting the one carbon cycle can have positive effects. sciencenewshighlights ScienceMission.

Cachexia is a metabolic disorder that causes uncontrolled weight loss and muscle wasting in chronic diseases and cancer. A new study shows that cachexia affects more than just muscles. Numerous organs respond in a coordinated manner, ultimately contributing to muscle loss. Analysis of metabolome and transcriptome data, along with glucose tracing in tumor-bearing mouse models, identified a novel mechanism that plays a key role in cancer-associated weight loss.

A loss of 10% of body weight within six months – what may sound desirable in some contexts – often causes uncertainty and frustration in cancer patients with cachexia, as they are unable to maintain or gain body weight despite wanting to. Cachexia (from the Greek kakós, “bad,” and héxis, “condition”) affects 50–80% of all cancer patients, reduces quality of life, diminishes the effectiveness of cancer therapies, and increases mortality.