Alzheimer’s disease is often measured in statistics: millions affected worldwide, cases rising sharply, costs climbing into the trillions. For families, the disease is experienced far more intimately. “It’s a slow bereavement,” says Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Professor Nicholas Tonks, whose mother lived with Alzheimer’s. “You lose the person piece by piece.”

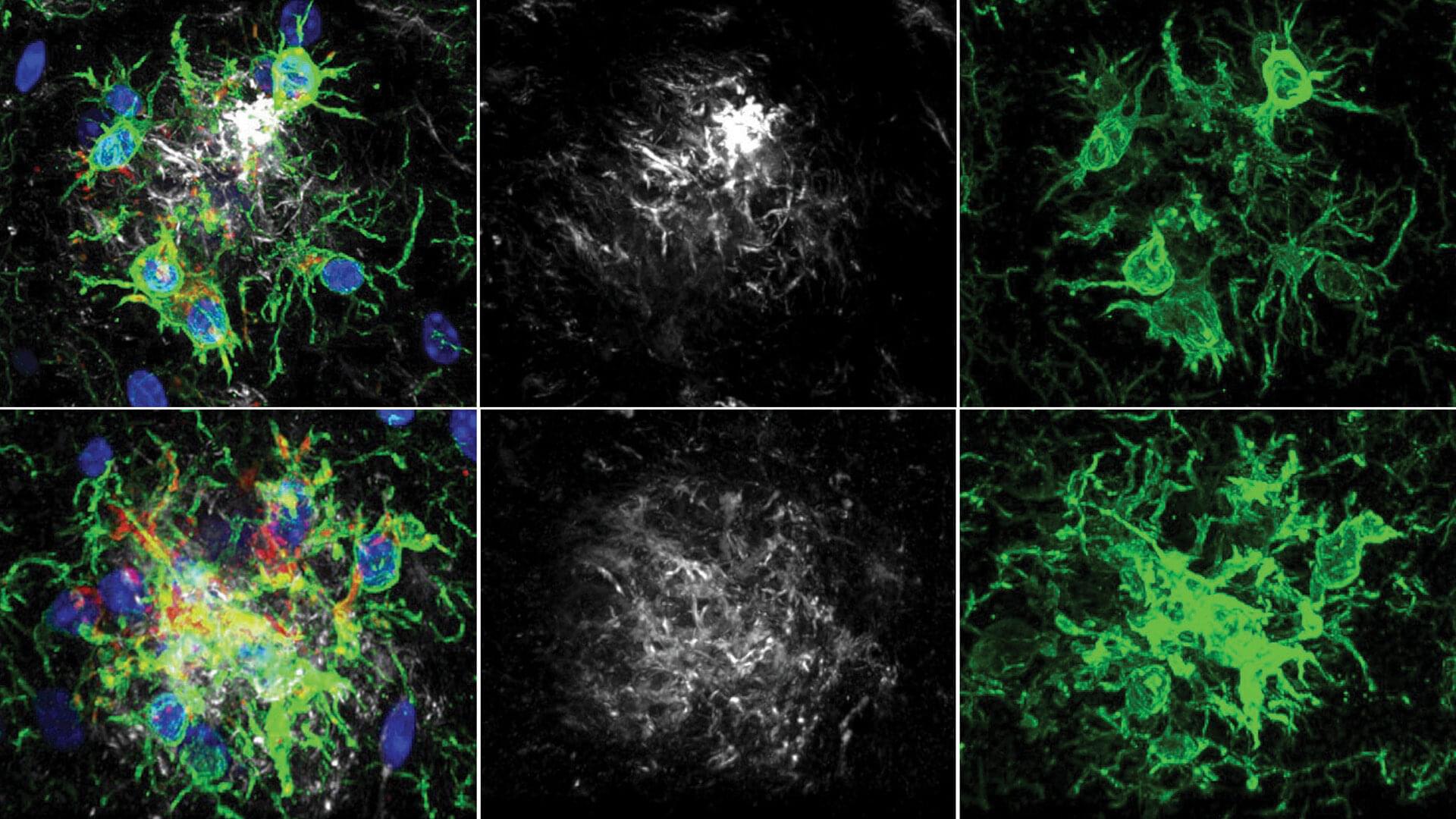

There’s a lot of discussion about how the neurodegenerative disorder may be caused by a buildup of “plaque” in the brain. When someone refers to this plaque, they’re talking about amyloid-β (Aβ), a peptide that occurs naturally but can accumulate and come together. This is known to promote Alzheimer’s disease development.

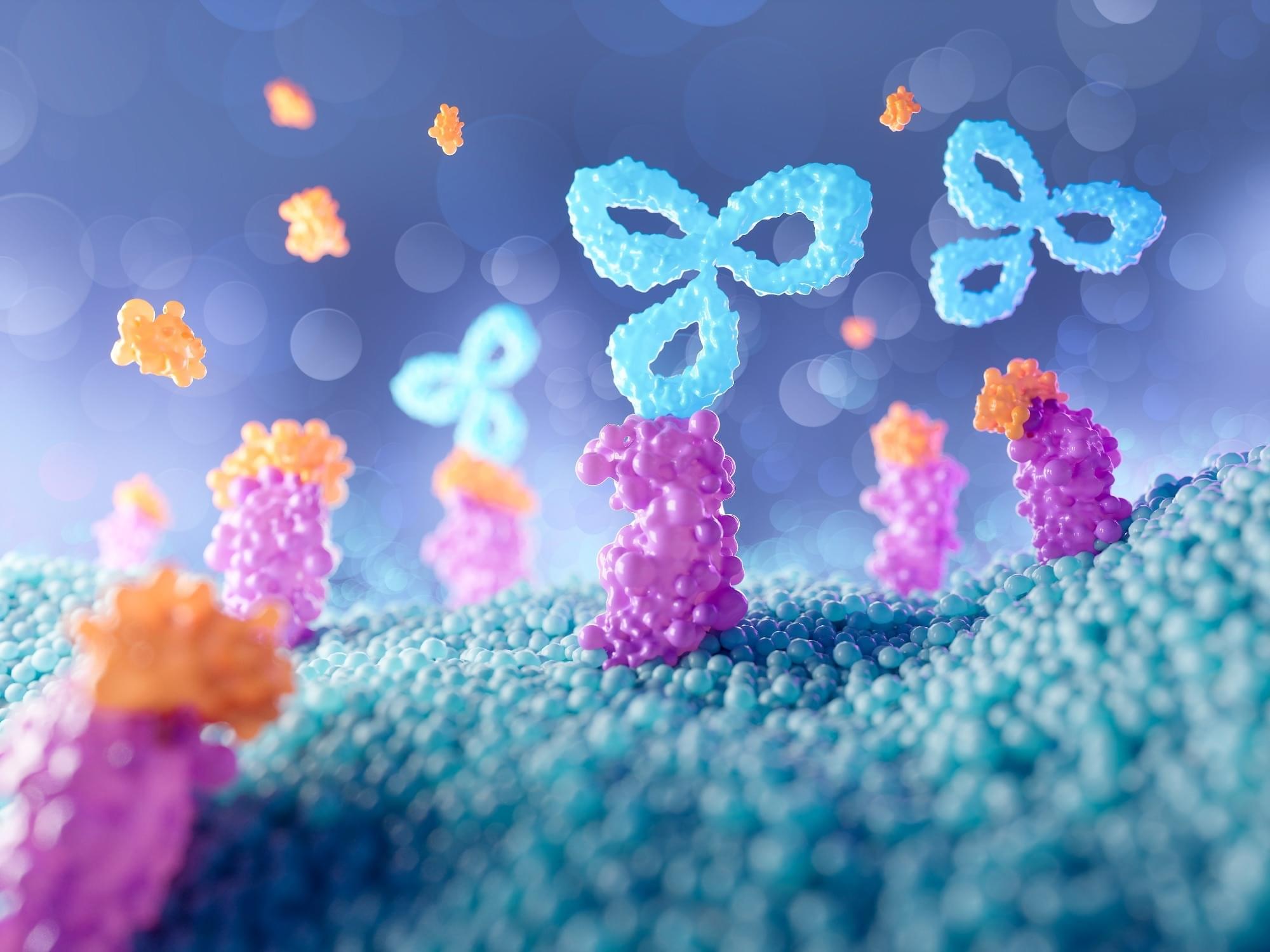

Now, Tonks, graduate student Yuxin Cen, and postdoctoral fellow Steven Ribeiro Alves have discovered that inhibiting a protein called PTP1B improves learning and memory in an Alzheimer’s disease mouse model. The findings are published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.