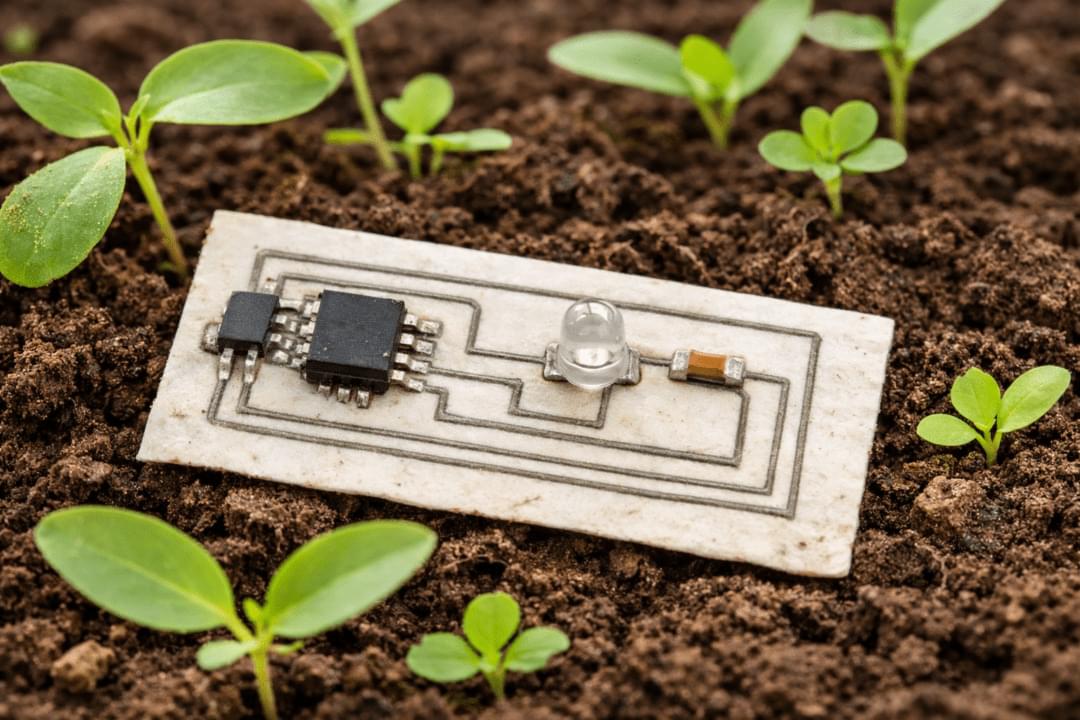

Researchers at the University of Glasgow have developed an almost entirely biodegradable PCB using zinc conductors and bio-derived substrate materials. The work aims to reduce the environmental impact of electronic waste by replacing conventional copper-based PCBs in applications designed for short operational lifetimes.

For eeNews Europe readers, the research is relevant as it explores alternative PCB materials and manufacturing methods that could be applied to disposable and low-duty-cycle electronics, including sensing and IoT-related devices.

The approach differs from conventional PCB fabrication, which typically involves etching copper from a full sheet. Instead, the researchers use what they describe as a growth and transfer additive manufacturing process, depositing conductive material only where tracks are required. According to the team, this reduces metal usage and avoids the use of harsh chemical etchants.