Frontier can work with OpenAI agents, enterprise-build agents, as well as agents from third parties like Google, Microsoft and Anthropic.

What does it take to turn bold ideas into life-saving medicine?

In this episode of The Big Question, we sit down with @MIT’s Dr. Robert Langer, one of the founding figures of bioengineering and among the most cited scientists in the world, to explore how engineering has reshaped modern healthcare. From early failures and rejected grants to breakthroughs that changed medicine, Langer reflects on a career built around persistence and problem-solving. His work helped lay the foundation for technologies that deliver large biological molecules, like proteins and RNA, into the body, a challenge once thought impossible. Those advances now underpin everything from targeted cancer therapies to the mRNA vaccines that transformed the COVID-19 response.

The conversation looks forward as well as back, diving into the future of medicine through engineered solutions such as artificial skin for burn victims, FDA-approved synthetic blood vessels, and organs-on-chips that mimic human biology to speed up drug testing while reducing reliance on animal models. Langer explains how nanoparticles safely carry genetic instructions into cells, how mRNA vaccines train the immune system without altering DNA, and why engineering delivery, getting the right treatment to the right place in the body, remains one of medicine’s biggest challenges. From personalized cancer vaccines to tissue engineering and rapid drug development, this episode reveals how science, persistence, and engineering come together to push the boundaries of what medicine can do next.

#Science #Medicine #Biotech #Health #LifeSciences.

Chapters:

00:00 Engineering the Future of Medicine.

01:55 Failure, Persistence, and Scientific Breakthroughs.

05:30 From Chemical Engineering to Patient Care.

08:40 Solving the Drug Delivery Problem.

11:20 Delivering Proteins, RNA, and DNA

14:10 The Origins of mRNA Technology.

17:30 How mRNA Vaccines Work.

20:40 Speed and Scale in Vaccine Development.

23:30 What mRNA Makes Possible Next.

26:10 Trust, Misinformation, and Vaccine Science.

28:50 Engineering Tissues and Organs.

31:20 Artificial Skin and Synthetic Blood Vessels.

33:40 Organs on Chips and Drug Testing.

36:10 Why Science Always Moves Forward.

The Big Question with the Museum of Science:

How Elon plans to launch a terawatt of GPUs into space.

## Elon Musk plans to launch a massive computing power of 1 terawatt of GPUs into space to advance AI, robotics, and make humanity multi-planetary, while ensuring responsible use and production. ## ## Questions to inspire discussion.

Space-Based AI Infrastructure.

Q: When will space-based data centers become economically superior to Earth-based ones? A: Space data centers will be the most economically compelling option in 30–36 months due to 5x more effective solar power (no batteries needed) and regulatory advantages in scaling compared to Earth.

☀️ Q: How much cheaper is space solar compared to ground solar? A: Space solar is 10x cheaper than ground solar because it requires no batteries and is 5x more effective, while Earth scaling faces tariffs and land/permit issues.

Q: What solar production capacity are SpaceX and Tesla planning? A: SpaceX and Tesla plan to produce 100 GW/year of solar cells for space, manufacturing from raw materials to finished cells in-house.

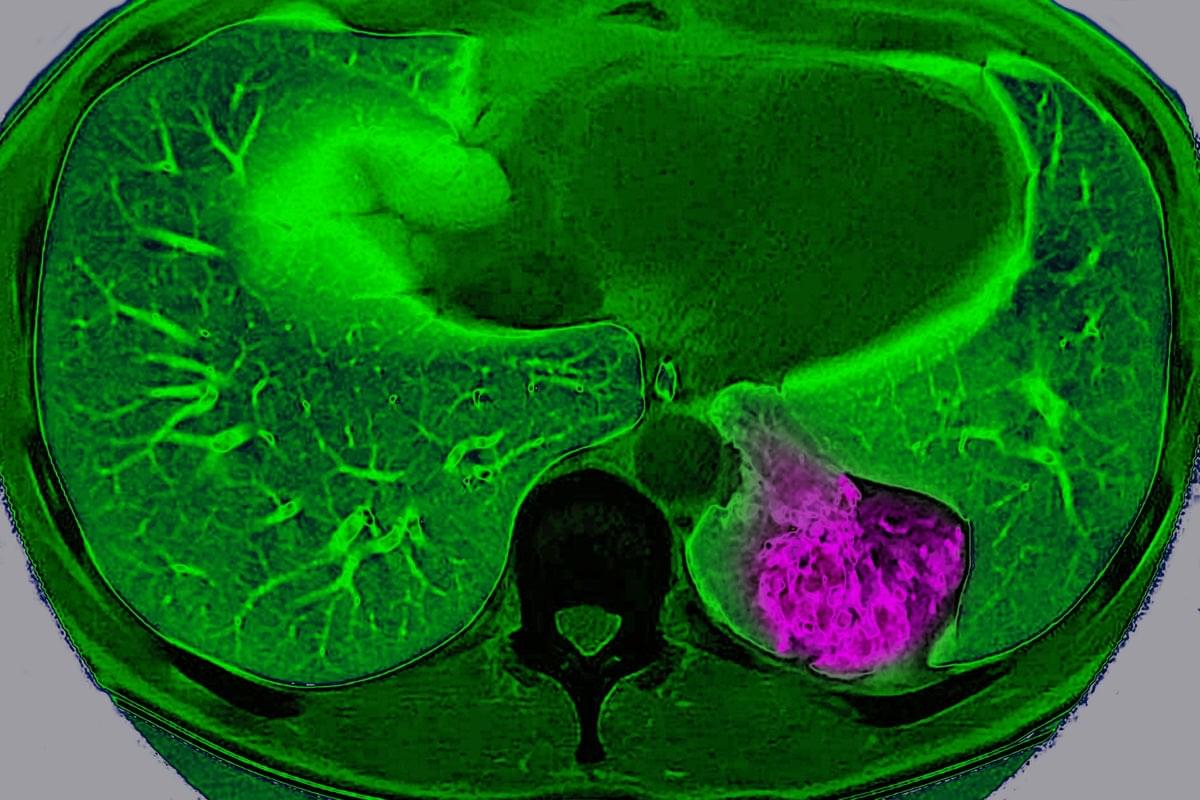

For years, scientists have viewed cancer as a localized glitch in which cells refuse to stop dividing. But a new study suggests that, in certain organs, tumors actively communicate with the brain to trick it into protecting them.

Scientists have long known that nerves grow into some tumors and that tumors containing lots of nerves usually lead to a worse prognosis. But they didn’t know exactly why. “Prior to our study, most of the focus has been this local interaction between the nerve [endings] and the tumor,” says Chengcheng Jin, an assistant professor of cancer biology at the University of Pennsylvania and a co-author of the study, which was published on Wednesday in Nature.

Jin and her colleagues discovered that lung cancer tumors in mice can use these nerve endings to communicate way beyond their close vicinity and send signals to the brain through a complex neuroimmune circuit. They also confirmed the circuit exists in humans.

✍️: Jacek Krywko 📸: BSIP/Universal Images Group via Getty Images.

Lung cancer tumor cells in mice communicate with the brain, sending signals to deactivate the body’s immune response, a study finds.

By Jacek Krywko edited by Tanya Lewis.

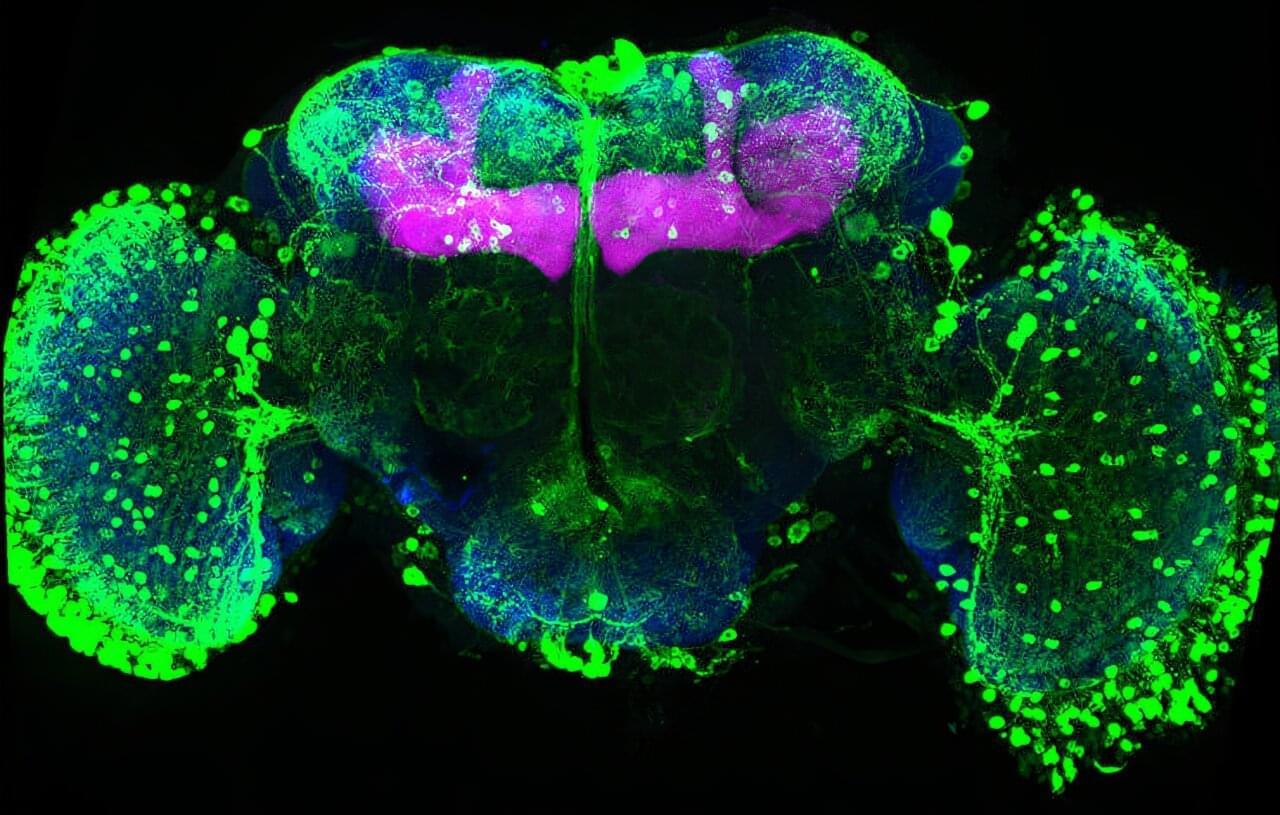

Memories must be flexible so animals can adapt when the world changes. FMI neuroscientists have found that in fruit flies, simply tasting a sugar reward again can weaken all previous associated memories. This process may inspire new ways to safely update harmful or unwanted memories. The paper is published in the journal Current Biology.

Memories help animals survive by guiding them on what to look for and what to avoid, such as remembering the smell of food or the warning signs of danger. But in a constantly changing world, those memories must also remain flexible. If a reward or threat no longer has the same meaning, the brain needs ways to update what it has learned without completely forgetting the past.

Olympic skiers, bobsledders and speed skaters all have to master one critical moment: when to start. As athletes prepare for the upcoming Winter Olympics, that split second is in the spotlight because when everyone is fast, strong and skilled, a moment of hesitation can separate gold from silver. Research from Carnegie Mellon University helps explain why that split-second pause happens and how the brain controls it, offering insight not only into elite athletic performance, but also how people make everyday decisions when the outcome isn’t clear.

Eric Yttri, associate professor of biological sciences, wanted to study how the brain decides when to act and when to wait, especially when the outcome is uncertain. He said to think about the moment the puck drops at a heated rivalry hockey game.

“Move too early, you get ejected from the faceoff. Move too late, and the puck is already gone. Having that sort of fine control on your ability to delay your action is really key,” Yttri said. “It’s a sword that cuts both ways.”

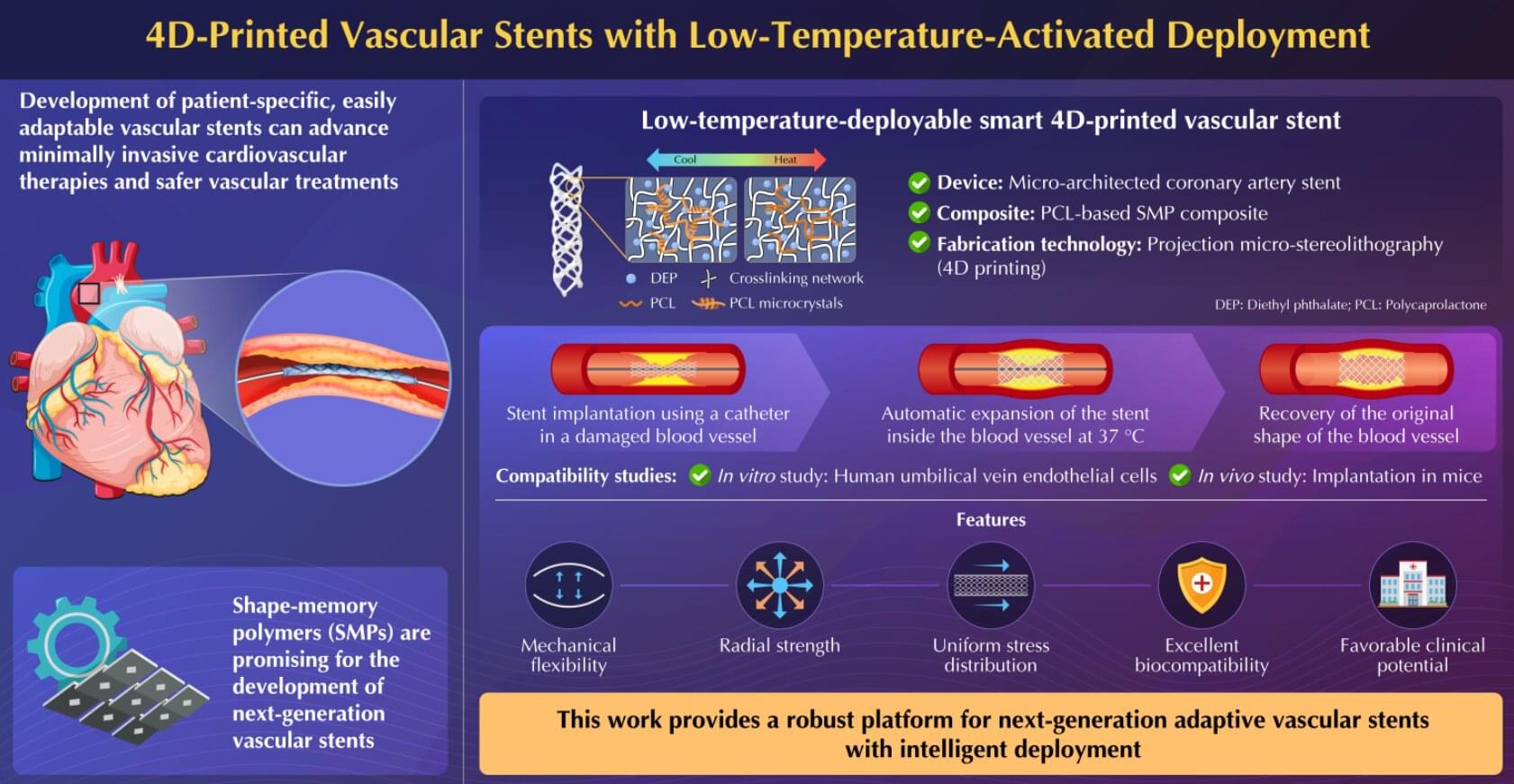

Next-generation vascular stents can make cardiovascular therapies minimally invasive and vascular treatments safe and less burdensome. In a new advancement, researchers from Japan and China have successfully proposed a novel adaptive 4D-printed vascular stent based on shape-memory polymer composite. The stent exhibits mechanical flexibility, radial strength, biomechanical compliance, and cytocompatibility in in vitro and in vivo experiments, making them promising for future clinical applications.

Cardiovascular diseases constitute a major global health concern. Various complications that affect normal blood flow in arteries and veins, such as stroke, blood clot formation in veins, blood vessel rupture, and coronary artery disease, often require vascular treatments. However, existing vascular stent devices often require complex, invasive deployment procedures, making it necessary to explore novel materials and manufacturing technologies that could enable such medical devices to work more naturally with the human body.

Moreover, the development of patient-specific, adaptively deployable vascular stents is crucial to further advance minimally invasive cardiovascular therapies and make vascular treatments safe and less burdensome for both patients and health care providers.

A cross-sectional study of Chinese college students found ADHD symptoms were associated with internet addiction, with insomnia and executive dysfunction acting as mediating factors. Moderate and high physical activity levels were also linked with lower internet addiction symptoms, although causality cannot be inferred.

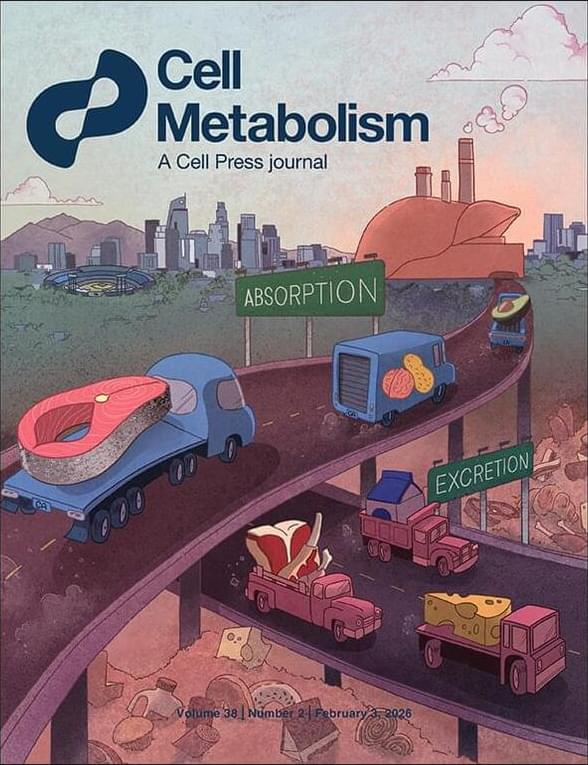

Human MASLD is a diurnal disease!

Circadian rhythm controls hepatic lipid and glucose metabolism, but it is not known if diurnal patterns exist in functional processes governing intrahepatic lipid accumulation in humans.

By studying metabolism across day and night in human participants, the researchers show that metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) is a nighttime disease driven by upregulated hepatic and peripheral insulin resistance with lower plasma insulin levels at night, secondary to reduced insulin secretion and elevated insulin clearance.

These daily patterns persist after weight loss, suggesting that nighttime metabolic dysfunction is a key driver of liver fat accumulation. sciencenewshighlights ScienceMission https://sciencemission.com/MASLD-is-a-diurnal-disease

By studying metabolism across day and night in human participants, Marjot et al. show that MASLD is a nighttime disease driven by poor insulin action and low insulin levels. These daily patterns persist after weight loss, suggesting that nighttime metabolic dysfunction is a key driver of liver fat accumulation.

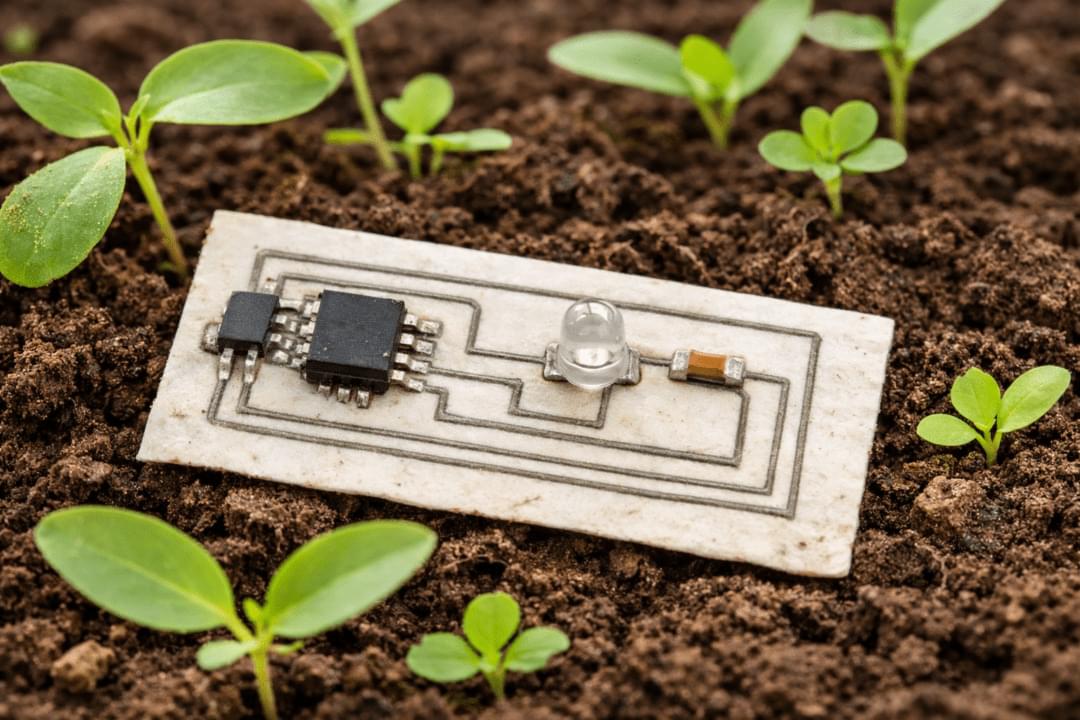

Researchers at the University of Glasgow have developed an almost entirely biodegradable PCB using zinc conductors and bio-derived substrate materials. The work aims to reduce the environmental impact of electronic waste by replacing conventional copper-based PCBs in applications designed for short operational lifetimes.

For eeNews Europe readers, the research is relevant as it explores alternative PCB materials and manufacturing methods that could be applied to disposable and low-duty-cycle electronics, including sensing and IoT-related devices.

The approach differs from conventional PCB fabrication, which typically involves etching copper from a full sheet. Instead, the researchers use what they describe as a growth and transfer additive manufacturing process, depositing conductive material only where tracks are required. According to the team, this reduces metal usage and avoids the use of harsh chemical etchants.