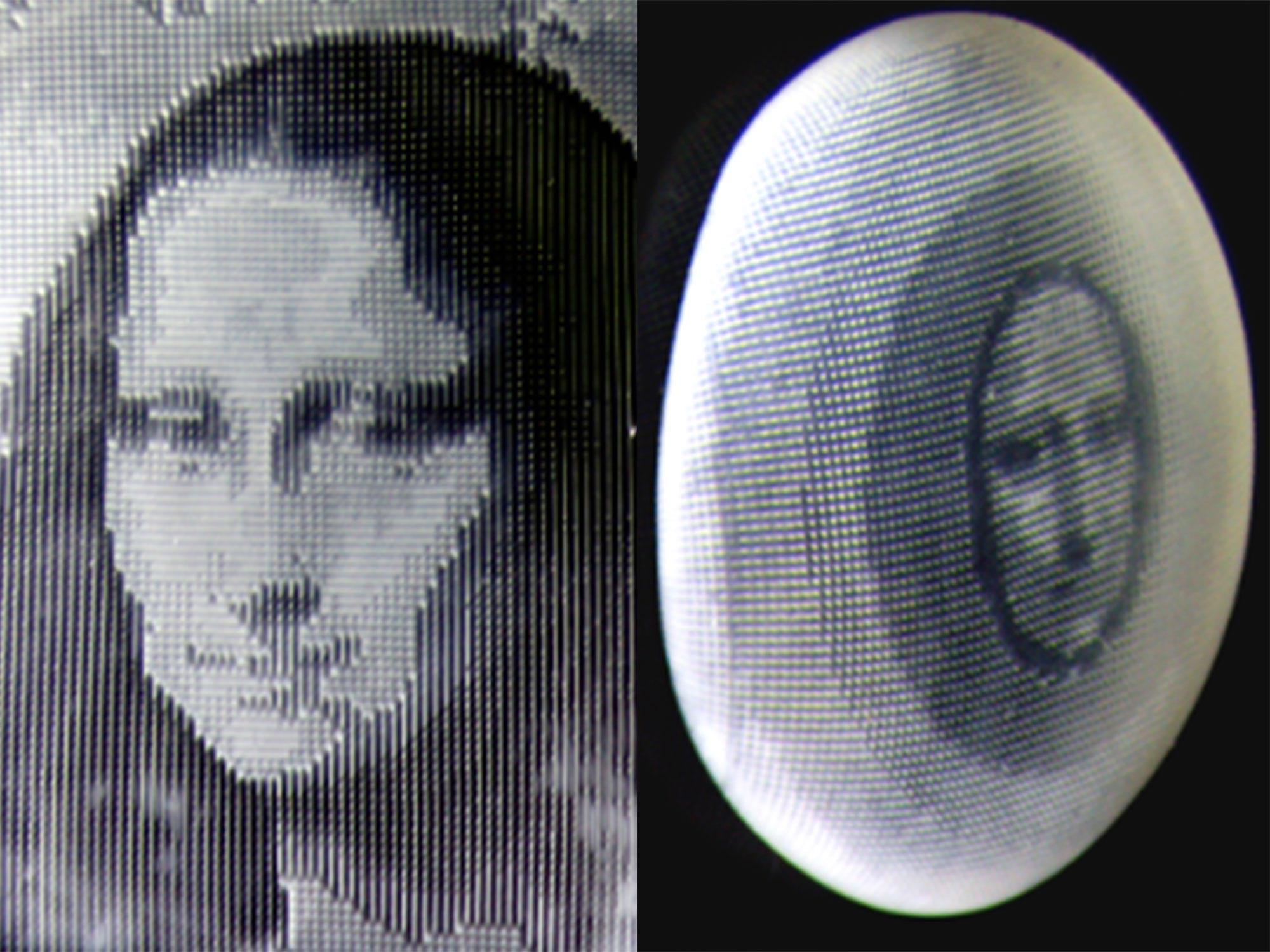

Despite being riddled with impurities and defects, solution-processed lead-halide perovskites are surprisingly efficient at converting solar energy into electricity. Their efficiency is approaching that of silicon-based solar cells, the industry standard. In a new study published in Nature Communications, physicists at the Institute of Science and Technology Austria (ISTA) present a comprehensive explanation of the mechanism behind perovskite efficiency that has long perplexed researchers.

How can a device assembled with minimal sophistication rival state-of-the-art technology perfected over decades? Over the past 15 years, materials research has witnessed the rise of lead-halide-based perovskites as prospective next-generation solar-cell materials. The puzzle is that despite similar performance, perovskite solar cells are fabricated using inexpensive solution-based techniques, while the industry-standard silicon cells require ultra-pure single-crystal wafers.

Now, postdoc Dmytro Rak and assistant professor Zhanybek Alpichshev at the Institute of Science and Technology Austria (ISTA) have uncovered the mechanism behind the unique photovoltaic properties of perovskites. Their key finding is that while silicon-based technology relies on the absence of impurities, the opposite is true in perovskites: It is the natural network of structural defects in these materials that enables the long-range charge transport necessary for efficient photovoltaic energy harvesting.