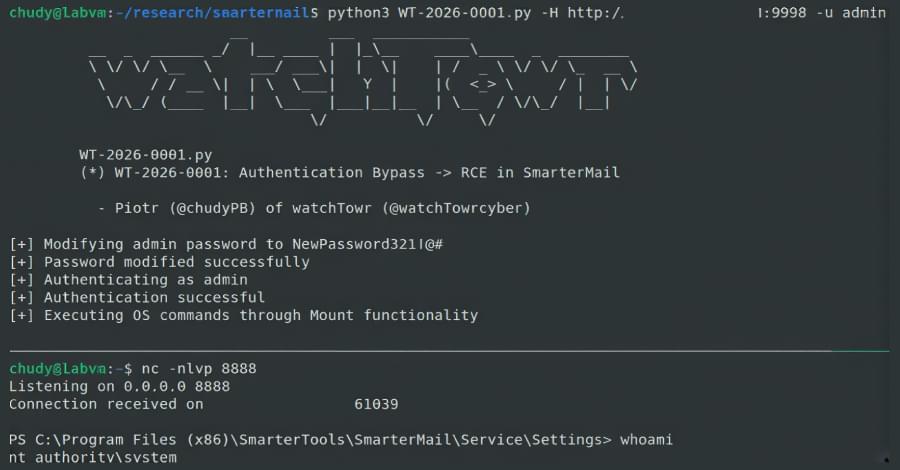

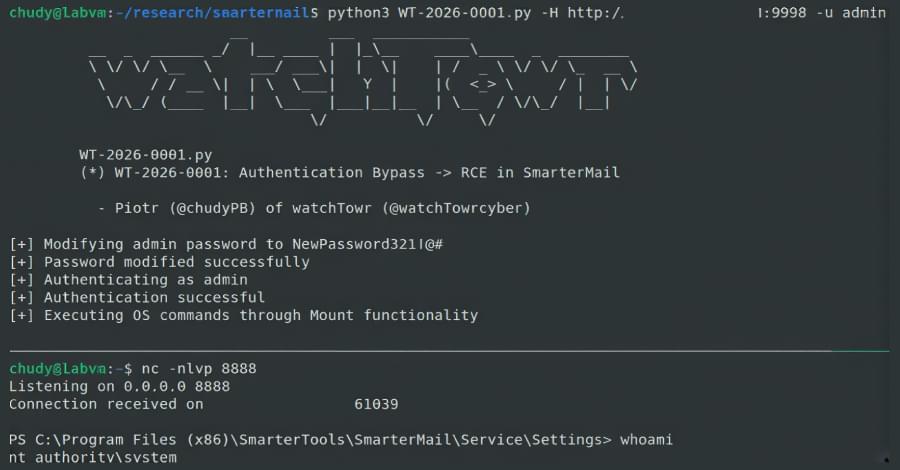

A newly patched SmarterMail flaws is being exploited in the wild, allowing attackers to reset admin passwords and gain SYSTEM-level code execution.

An operational security failure allowed researchers to recover data that the INC ransomware gang stole from a dozen U.S. organizations.

A deep forensic examination of the artifacts left behind uncovered tooling that had not been used in the investigated attack, but exposed attacker infrastructure that stored data exfiltrated from multiple victims.

The operation was conducted by Cyber Centaurs, a digital forensics and incident response company that disclosed its success last November and now shared the full details with BleepingComputer.

Okta is warning about custom phishing kits built specifically for voice-based social engineering (vishing) attacks. BleepingComputer has learned that these kits are being used in active attacks to steal Okta SSO credentials for data theft.

In a new report released today by Okta, researchers explain that the phishing kits are sold as part of an “as a service” model and are actively being used by multiple hacking groups to target identity providers, including Google, Microsoft, and Okta, and cryptocurrency platforms.

Unlike typical static phishing pages, these adversary-in-the-middle platforms are designed for live interaction via voice calls, allowing attackers to change content and display dialogs in real time as a call progresses.

The developer of the popular curl command-line utility and library announced that the project will end its HackerOne security bug bounty program at the end of this month, after being overwhelmed by low-quality AI-generated vulnerability reports.

The change was first discovered in a pending commit to curl’s BUG-BOUNTY.md documentation, which removes all references to the HackerOne program.

Once merged, the file will be updated to state that the curl project no longer offers any rewards for reported bugs or vulnerabilities and will not help researchers obtain compensation from third parties either.

Wondering what your career looks like in our increasingly uncertain, AI-powered future? According to Palantir CEO Alex Karp, it’s going to involve less of the comfortable office work to which most people aspire, a more old fashioned grunt work with your hands.

Speaking at the World Economic Forum yesterday, Karp insisted that the future of work is vocational — not just for those already in manufacturing and the skilled trades, but for the majority of humanity.

In the age of AI, Karp told attendees at a forum, a strong formal education in any of the humanities will soon spell certain doom.

US-based artificial intelligence (AI) startup Logical Intelligence has appointed Yann LeCun, former chief AI scientist at Meta, as the founding chair of its Technical Research Board, the company announced on January 22.

LeCun, one of the world’s most influential AI researchers and a Turing Award winner, left Meta late last year to launch his own startup, Advanced Machine Intelligence Labs, focused on building “world models” that can understand and navigate the physical environment. His decision to join Logical Intelligence signals a growing interest in alternatives to large language models for high-risk, real-world systems.

The company, founded by Eve Bodnia, also announced its flagship reasoning engine, Kona 1.0. A live public demonstration of Kona has been released on the company’s website.