When your winter jacket slows heat escaping your body or the cardboard sleeve on your coffee keeps heat from reaching your hand, you’re seeing insulation in action. In both cases, the idea is the same: keep heat from flowing where you don’t want it. But this physics principle isn’t limited to heat.

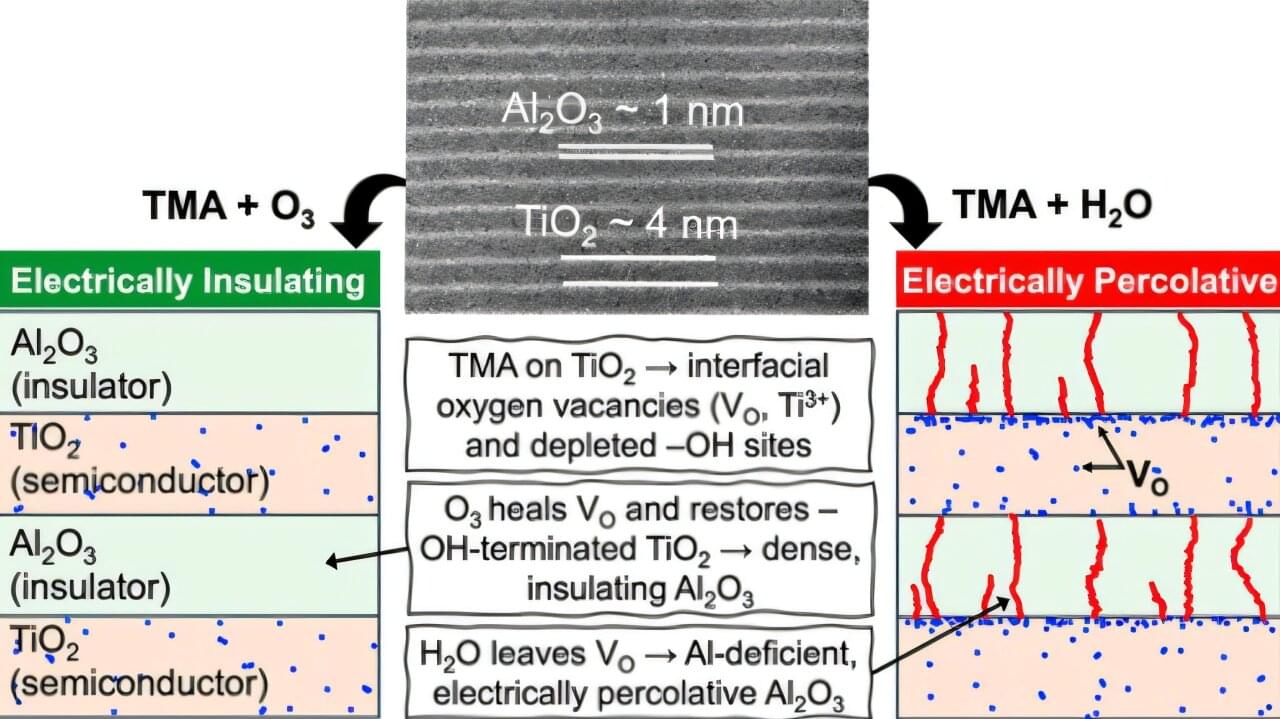

Electronics use it too, but with electricity. An electrical insulator stops current from flowing where it shouldn’t. That’s why power cords are wrapped in plastic. The plastic keeps electricity in the wire, not in your hand.

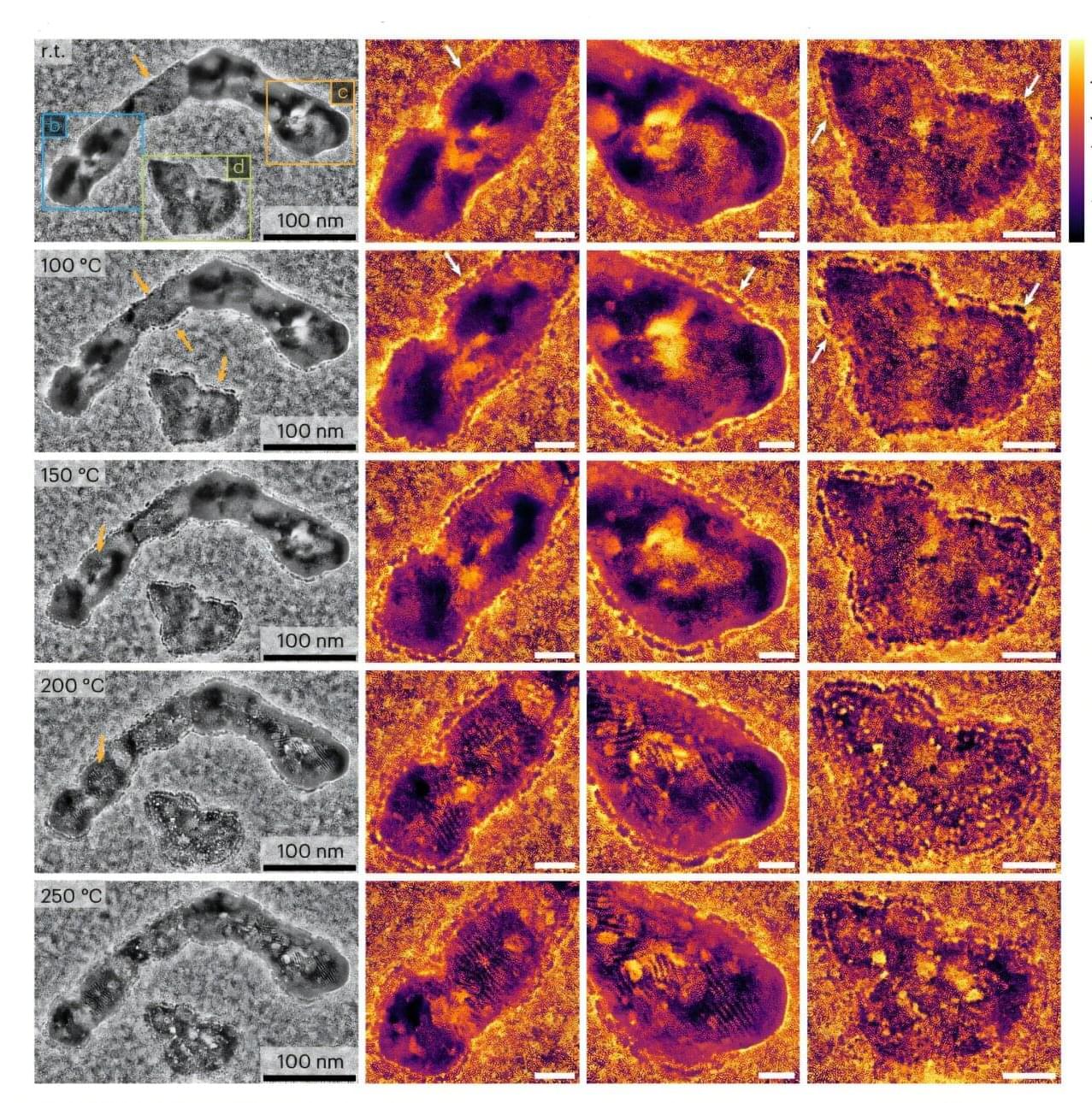

Inside electronics, insulators do more than keep the user safe. They also help devices store charge in a controlled way. In that role, engineers often call them dielectrics. These insulating layers sit at the heart of capacitors and transistors. A capacitor is a charge-storing component—think of it as a tiny battery, albeit one that fills up and empties much faster than a battery. A transistor is a tiny electrical switch. It can turn current on or off, or control how much current flows.