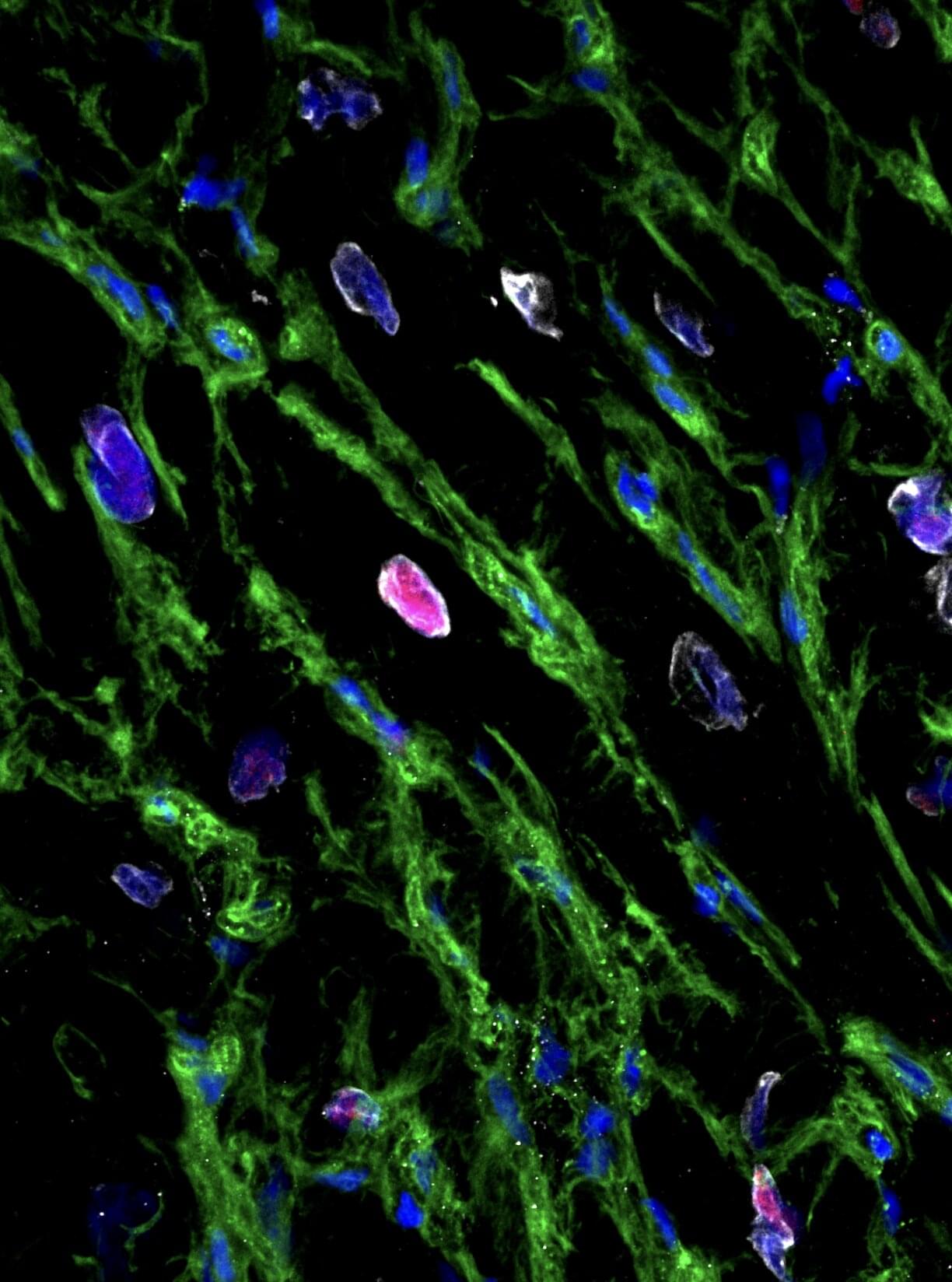

Pioneering research by experts at the University of Sydney, the Baird Institute and the Royal Prince Alfred Hospital in Sydney has shown that heart muscle cells regrow after a heart attack, opening up the possibility of new regenerative treatments for cardiovascular disease.

Following the publication of the study in Circulation Research, first author Dr. Robert Hume, from the Faculty of Medicine and Health and Charles Perkins Center, and Lead of Translational Research at the Baird Institute for Applied Heart and Lung Research, explained the significance of the finding: Until now we’ve thought that, because heart cells die after a heart attack, those areas of the heart were irreparably damaged, leaving the heart less able to pump blood to the body’s organs.

Our research shows that while the heart is left scarred after a heart attack, it produces new muscle cells, which opens up new possibilities.