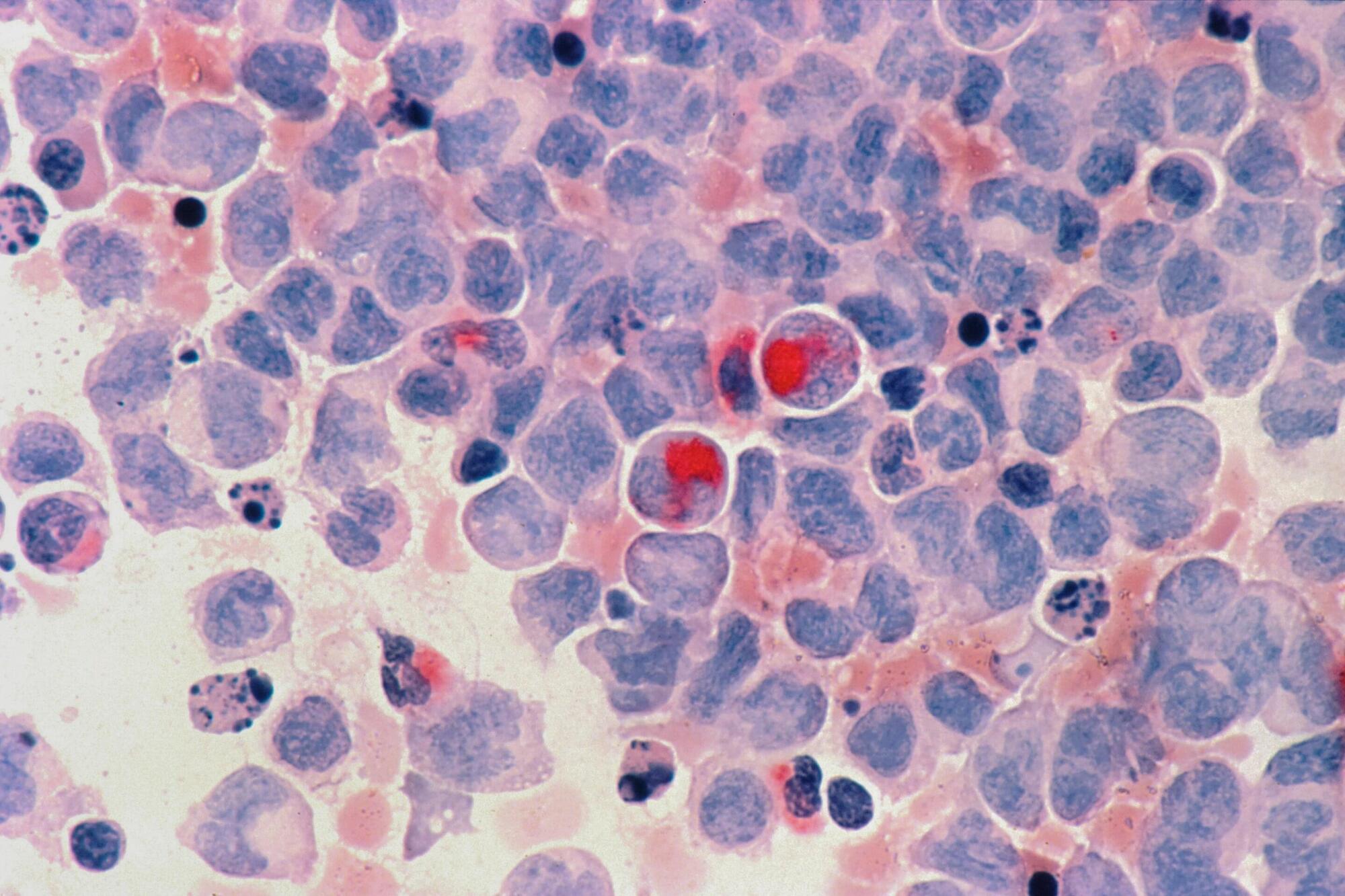

A research team at Oregon Health & Science University has discovered a promising new drug combination that may help people with acute myeloid leukemia overcome resistance to one of the most common frontline therapies.

In a study published in Cell Reports Medicine, researchers analyzed more than 300 acute myeloid leukemia, or AML, patient samples and found that pairing venetoclax, a standard AML drug, with palbociclib, a cell-cycle inhibitor currently approved for breast cancer, produced significantly stronger and more durable anti-leukemia activity than venetoclax alone. The findings were confirmed in human tissue samples, as well as in mouse models carrying human leukemia cells.

“Of the 25 drug combinations tested, venetoclax plus palbociclib was the most effective. That really motivated us to dig deeper into why it works so well—and why it appears to overcome resistance seen with current therapy,” said Melissa Stewart, Ph.D., research assistant professor at OHSU and lead author of the study.