Researchers from Guangxi University, China have developed a new gas sensor that detects ammonia with a record speed of 1.4 seconds. The sensor’s design mimics the structure of alveoli—the tiny air sacs in human lungs—while relying on a triboelectric nanogenerator (TENG) that converts mechanical energy into electrical energy. The sensor uses a process that is driven by A-droplets, which are tiny water droplets containing a trapped air bubble. These droplets exploit ammonia’s affinity for water to rapidly capture NH₃ when it is present.

When an ammonia-laden droplet falls onto the sensor, its mechanical impact completes an electrical circuit, generating signals that are converted into accurate gas measurements at a speed that exceeds existing ammonia gas sensors.

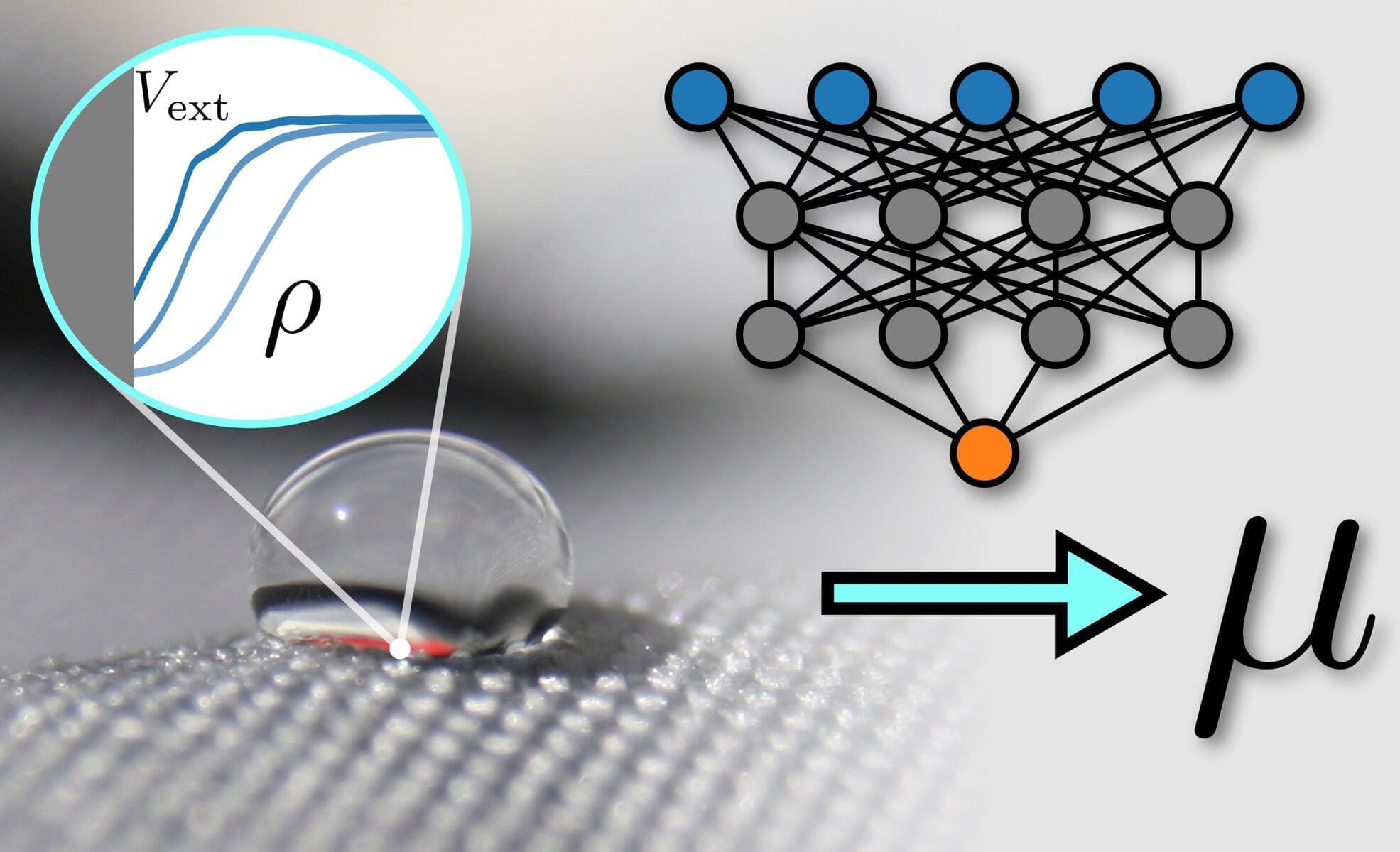

To take detection precision a step further, the team integrated an AI model that analyzes electrical signals and converts them into time-frequency images. After training on these images, the system classified ammonia into five concentration levels (0–200 ppm), achieving up to 98.4% detection accuracy.