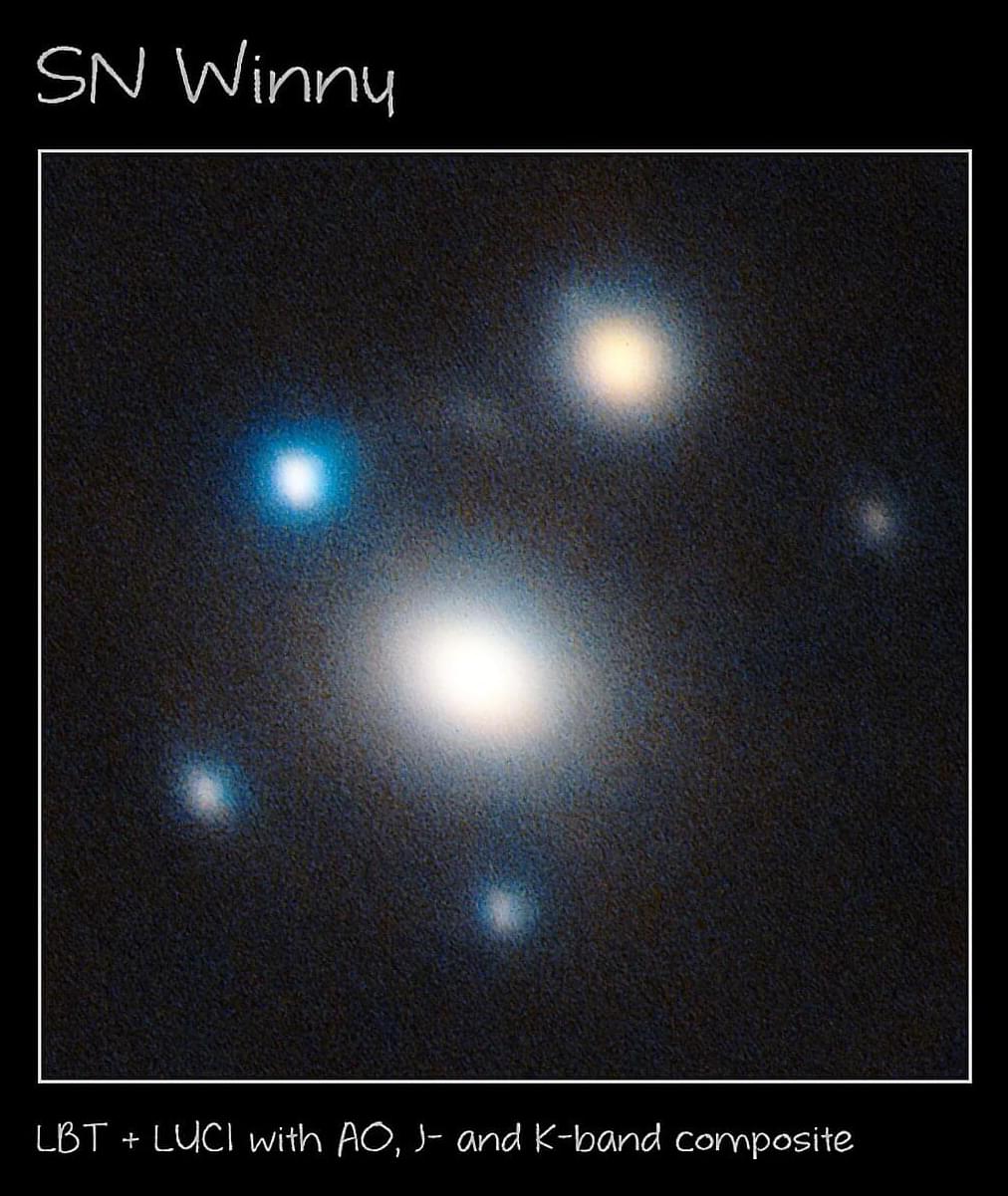

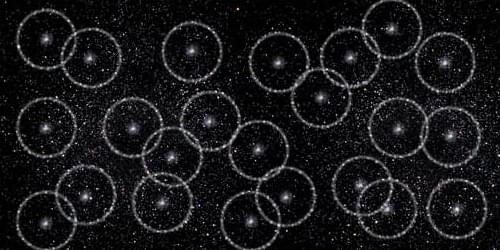

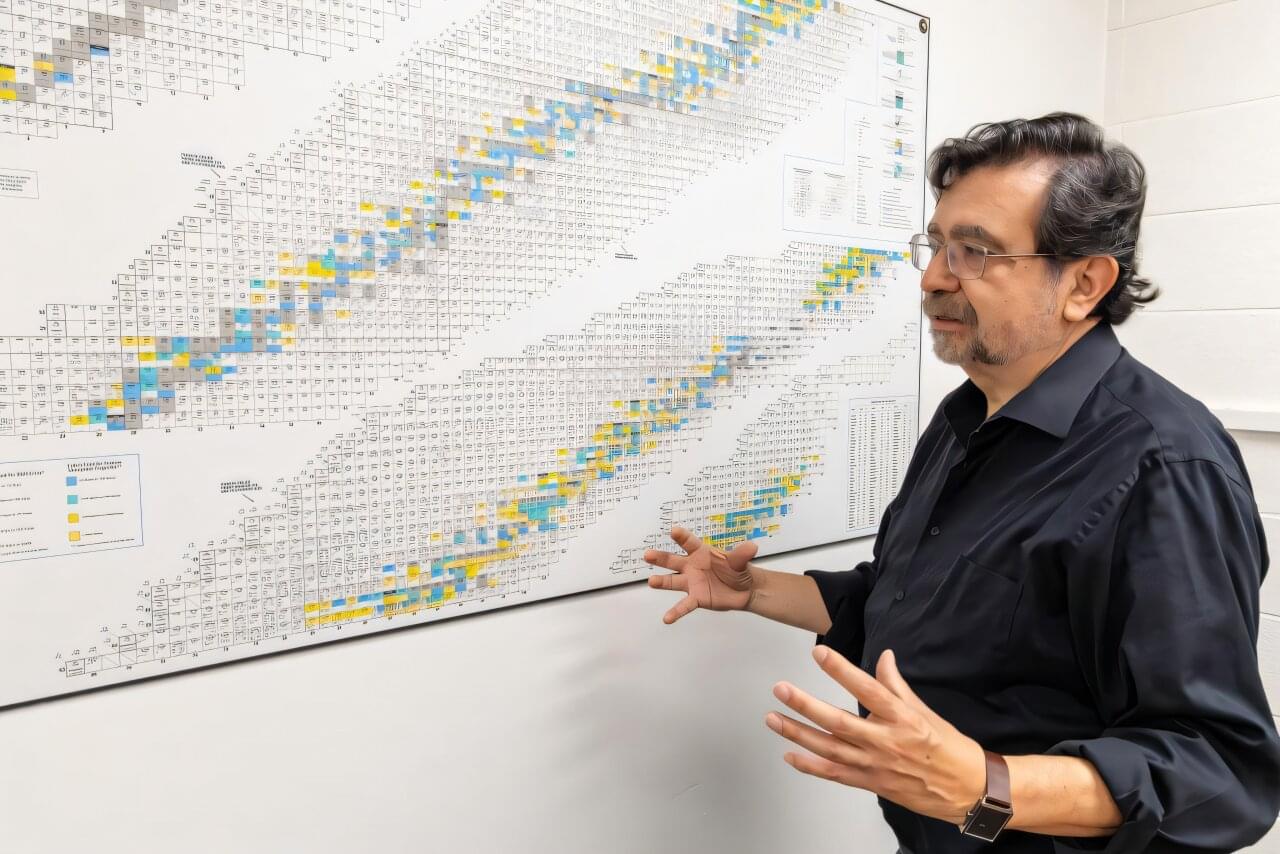

A recent discovery in astrophysics could overturn our current models of the Universe! A team of astronomers led by UMass Amherst “stacked” observations between the ALMA telescope and the JWST to confirm approximately 70 faint dusty galaxies at the edge of our universe, which were formed almost 13 billion years ago 🌠🔭. This shows that stars were being formed earlier than our current models predict — turning everything we thought we knew upside down. What does this mean for the future of astrophysics? Find out here: https://ow.ly/Nab150Yil7i astronomy.

Zavala, Jorge A., Faisst, Andreas L., Aravena, Manuel, Casey, Caitlin M., Kartaltepe, Jeyhan S., Martinez, Felix, Silverman, John D., Toft, Sune, Treister, Ezequiel, Akins, Hollis B., Algera, Hiddo, Barboza, Karina, Battisti, Andrew J., Brammer, Gabriel, Cai, Zheng, Champagne, Jaclyn, Drakos, Nicole E., Egami, Eiichi, Fan, Xiaohui, Franco, Maximilien, Fudamoto, Yoshinobu, Fujimoto, Seiji, Gillman, Steven, Gozaliasl, Ghassem, Harish, Santosh, Jin, Xiangyu, Kakiichi, Koki, Kakkad, Darshan, Koekemoer, Anton M., Lin, Ruqiu, Liu, Daizhong, Long, Arianna S., Magdis, Georgios E., Manning, Sinclaire, Martin, Crystal L., McKinney, Jed, Meyer, Romain, Rodighiero, Giulia, Salazar, Victoria, Sanders, David B., Shuntov, Marko, Talia, Margherita, Tanaka, Takumi S.