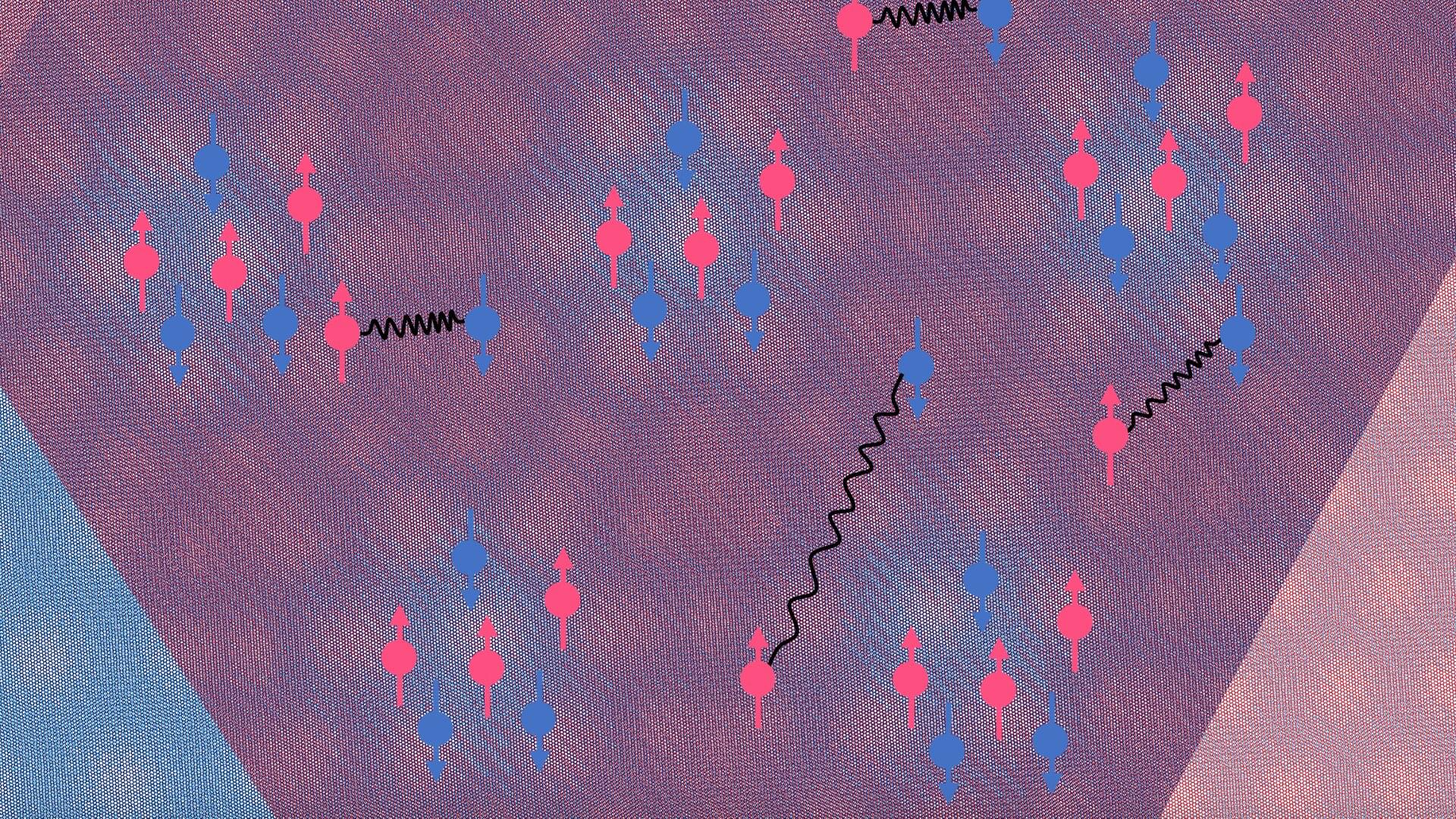

Quantum computers are alternative computing devices that process information, leveraging quantum mechanical effects, such as entanglement between different particles. Entanglement establishes a link between particles that allows them to share states in such a way that measuring one particle instantly affects the others, irrespective of the distance between them.

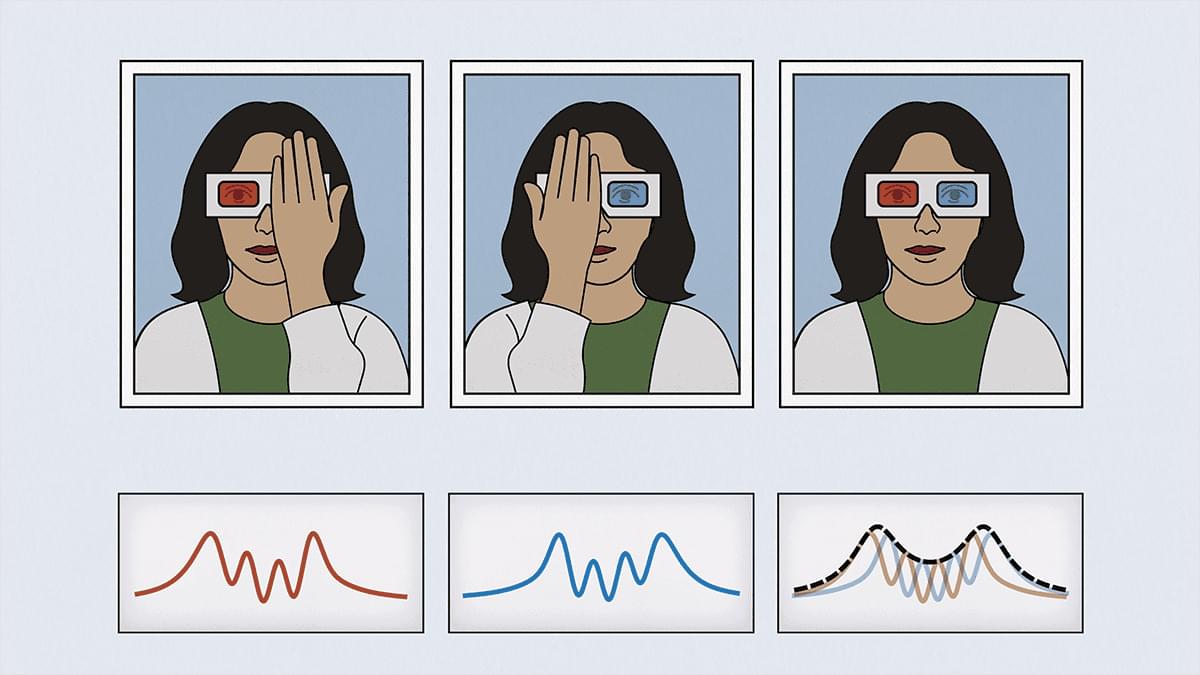

Quantum computers could, in principle, outperform classical computers in some optimization and computational tasks. However, they are also known to be highly sensitive to environmental disturbances (i.e., noise), which can cause quantum errors and adversely affect computations.

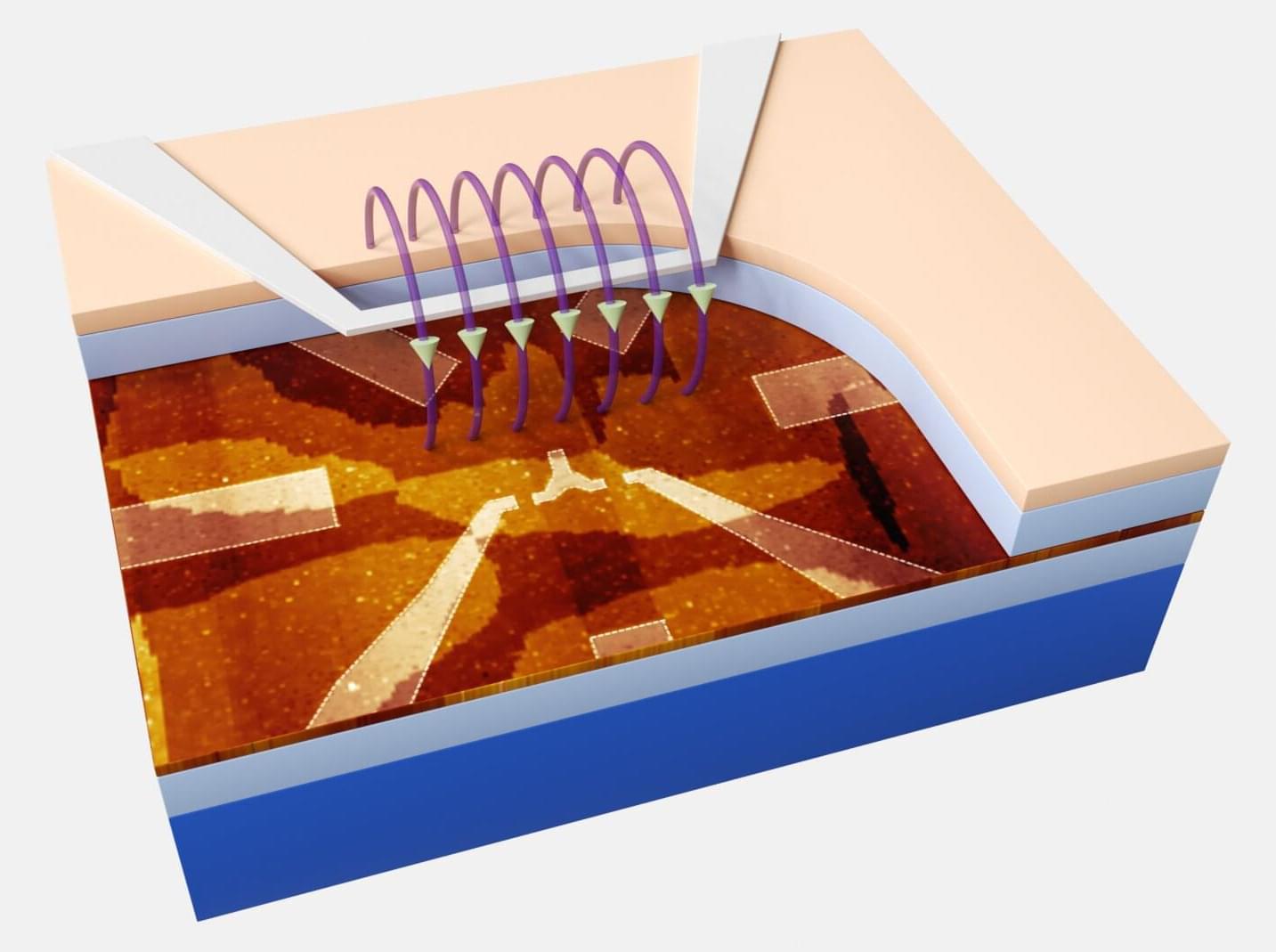

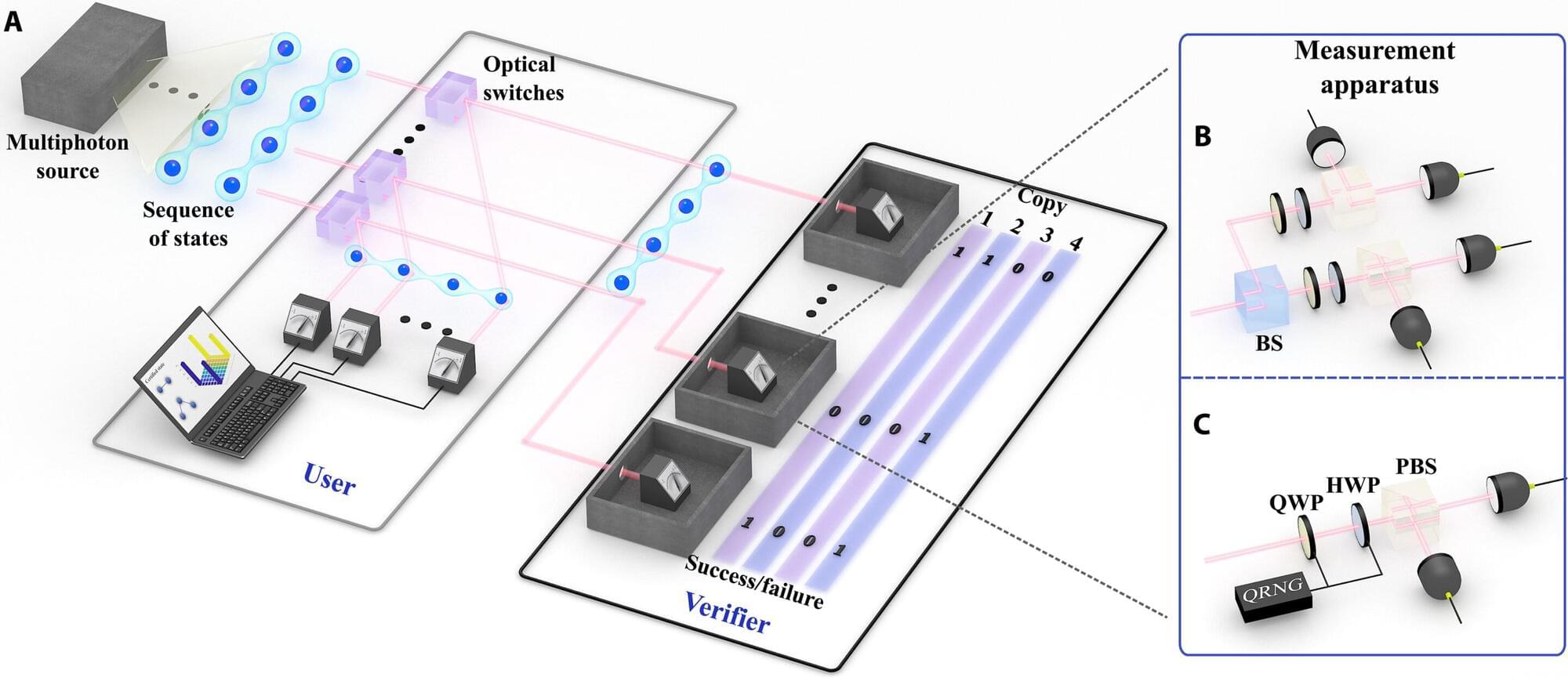

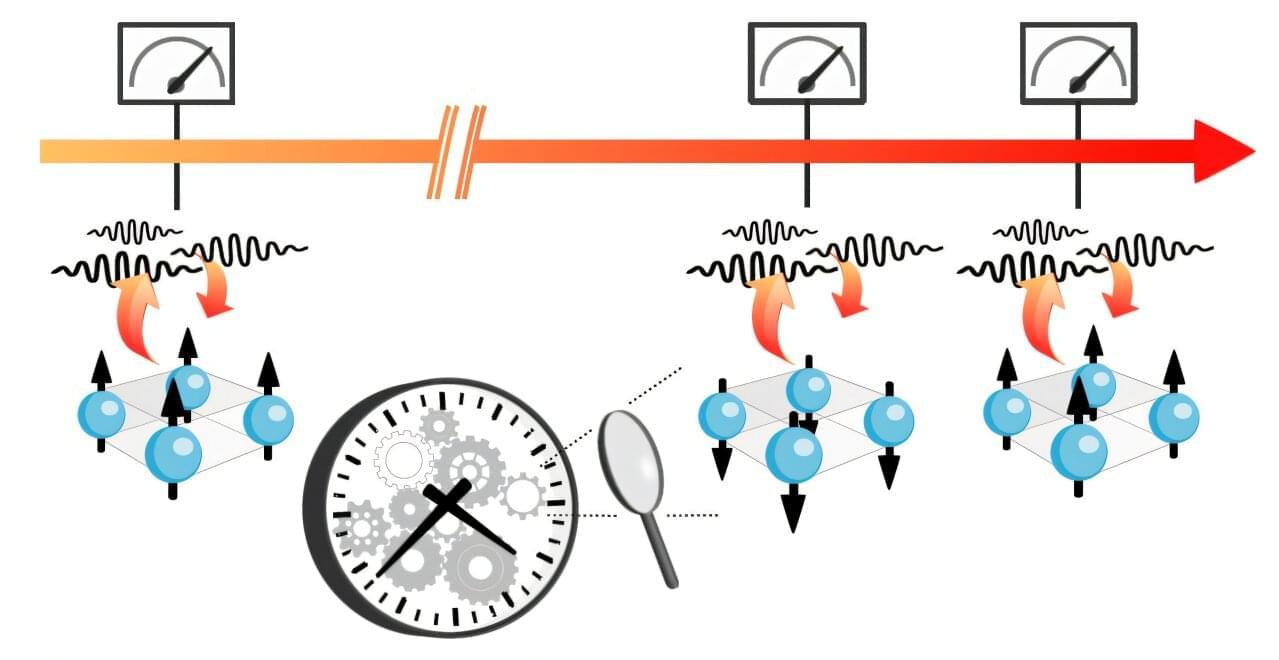

Researchers at the International Quantum Academy, Southern University of Science and Technology, and Hefei National Laboratory have developed a new approach to detect these errors in a silicon-based quantum processor. This error detection strategy, presented in a paper published in Nature Electronics, was found to successfully detect quantum errors in silicon qubits, while also preserving entanglement after their detection.