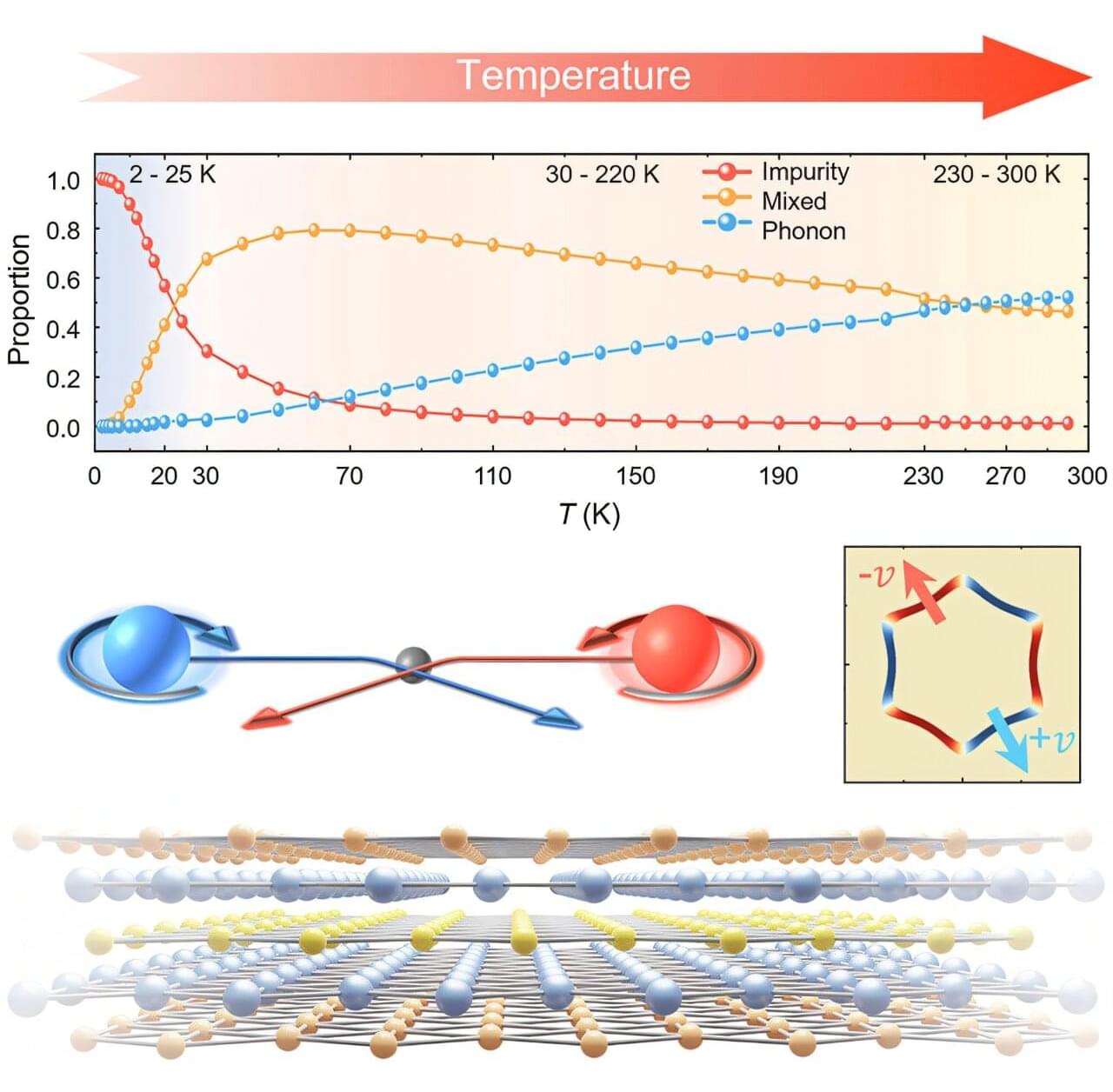

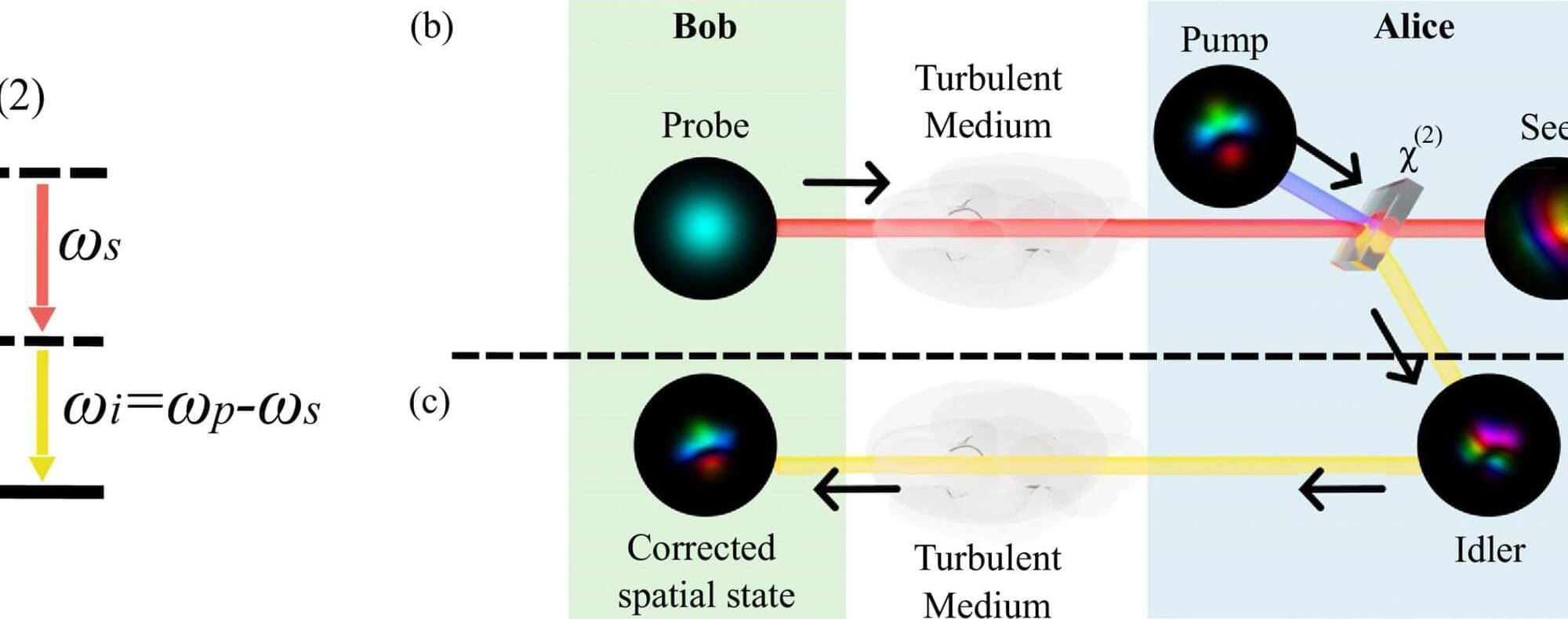

When you toss a coin, you put it into a higher-energy state until it falls back down again. It can then end up in one of two possible states: heads or tails. No matter which state the coin was in before, after the toss both outcomes are equally likely. A team at TU Wien has analyzed a quantum system that also has two equivalent ground states. By supplying energy through ion bombardment, this state can be changed.

Remarkably, however, the system behaves very differently from a coin toss: it switches every single time. After ion impact, it reliably ends up in the opposite state. For the experiment, the ion-beam equipment of TU Wien was transported to DESY in Hamburg. The crystals studied were provided by Kiel University (CAU), which also participated in the experiments at DESY. The research is published in the journal Nano Letters.