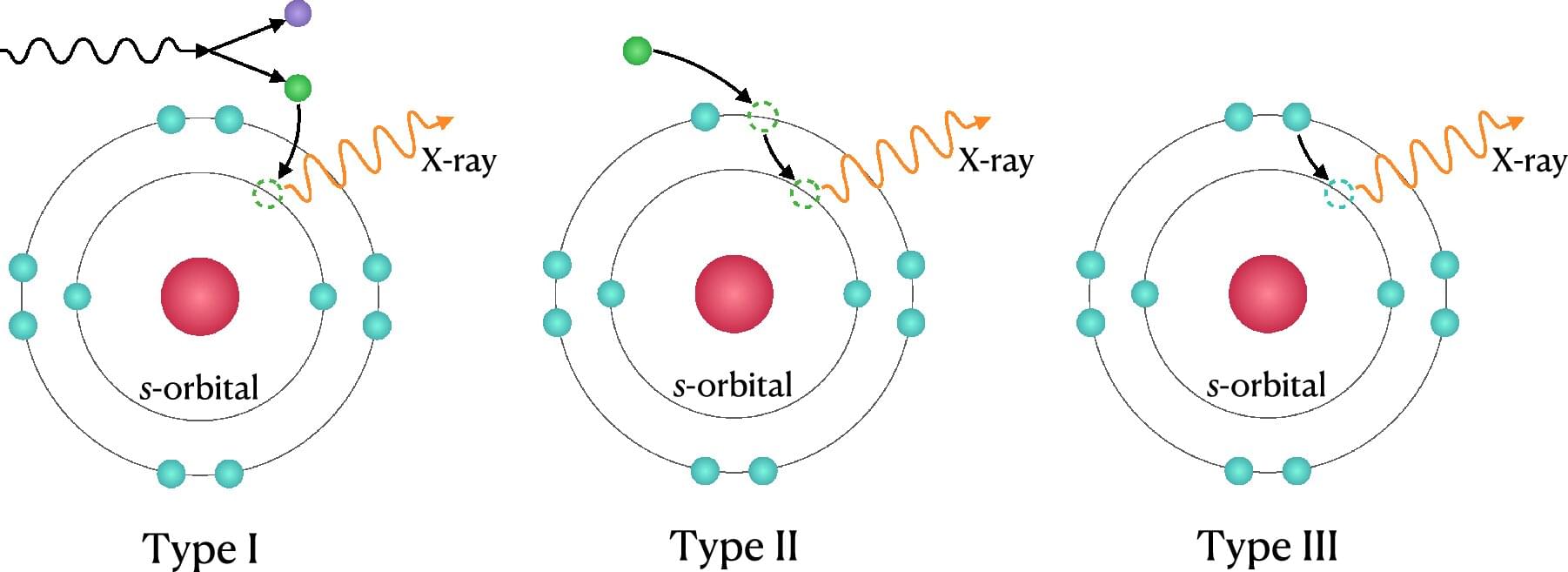

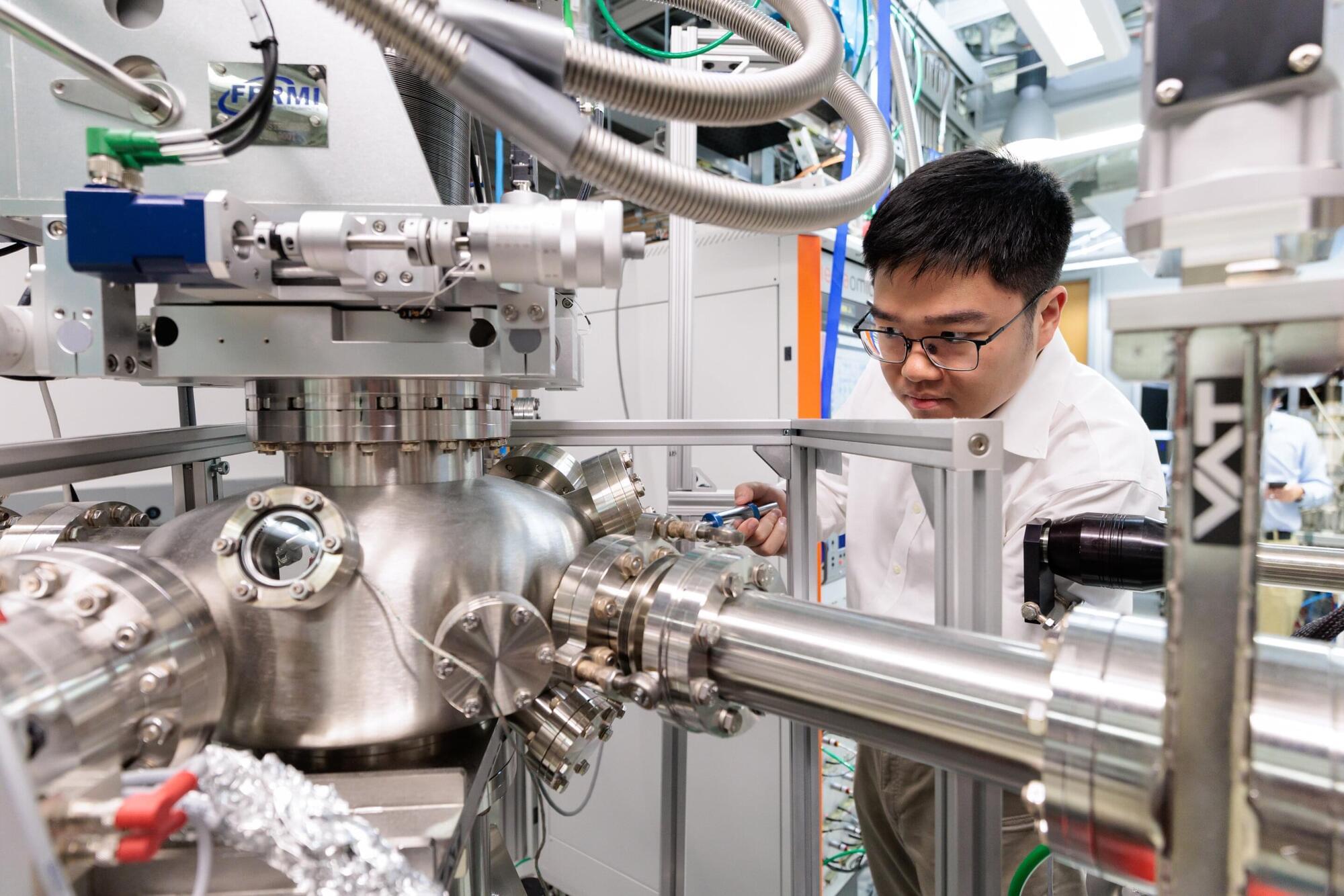

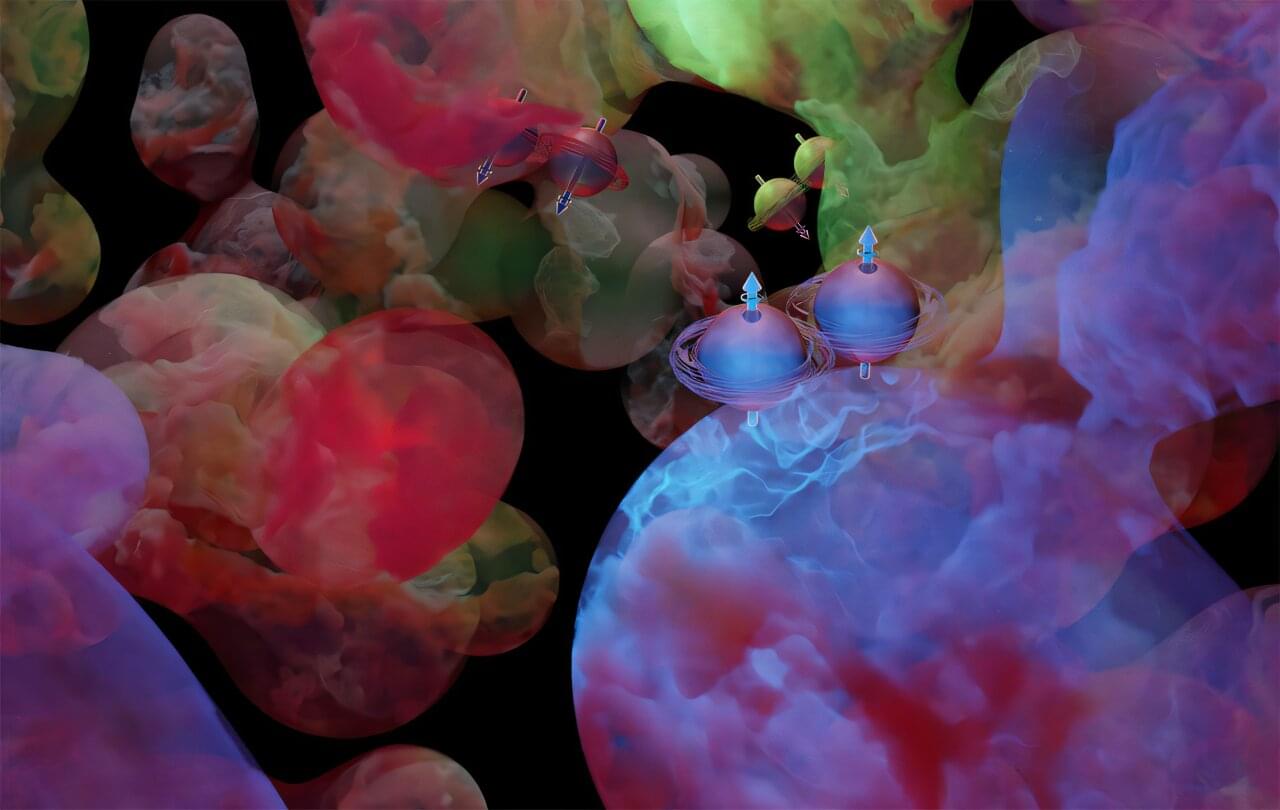

The Pauli exclusion principle is a cornerstone of the Standard Model of particle physics and is essential for the structure and stability of matter. Now an international collaboration of physicists has carried out one of the most stringent experimental tests to date of this foundational rule of quantum physics and has found no evidence of its violation. Using the VIP-2 experiment, the team has set the strongest limits so far for possible violations involving electrons in atomic systems, significantly constraining a range of speculative theories beyond the Standard Model, including those that suggest electrons have internal structure, and so-called “Quon models.” Their experiment was reported in Scientific Reports in November 2025.

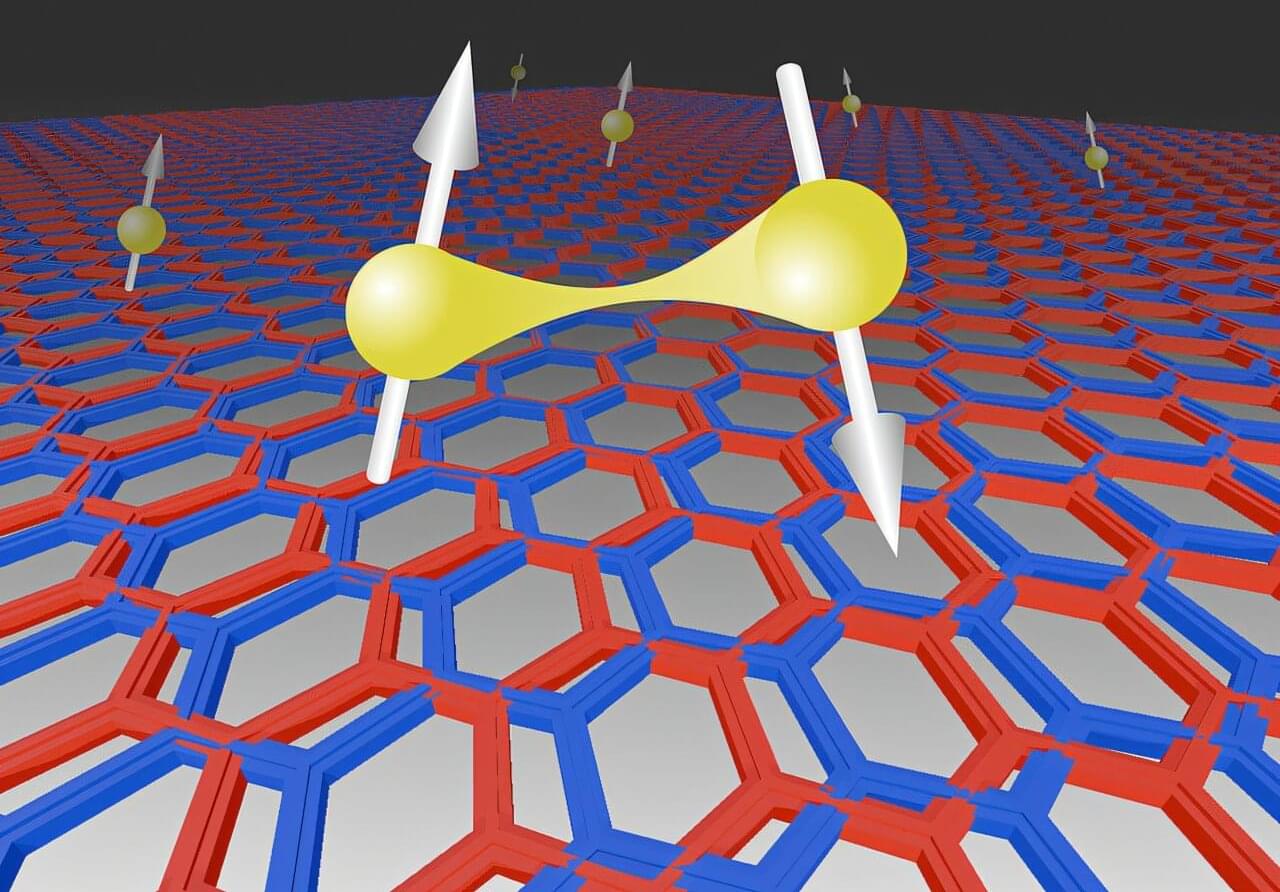

Austrian-Swiss physicist Wolfgang Pauli outlined the exclusion principle in 1925. It states that two identical “fermions” (a class of particles that includes electrons) cannot occupy the same quantum state. It explains why electrons fill atomic shells, why solids have rigidity, and why dense objects such as white dwarf stars do not collapse under gravity.

However, since its inception, physicists have been searching for signs that the Pauli exclusion principle may be violated in extreme conditions. “If the Pauli exclusion principle were violated, even at an extremely small level, the consequences would cascade from atomic physics all the way to astrophysics,” says FQxI member and physicist Catalina Curceanu of the Italian National Institute for Nuclear Physics (INFN), in Frascati, who is the spokesperson of the VIP-2 collaboration.