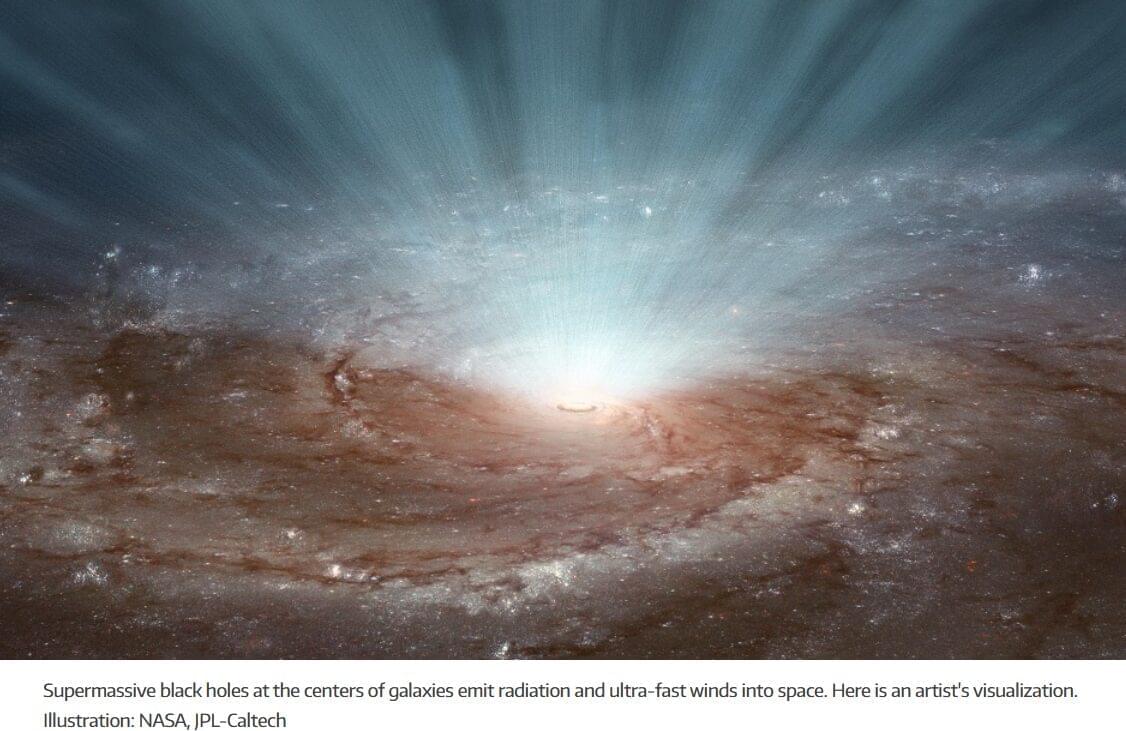

Could black holes help explain high-energy cosmic radiation?

Scientists may have finally uncovered the mystery behind ultra-high-energy cosmic rays — the most powerful particles known in the universe. A team from NTNU suggests that colossal winds from supermassive black holes could be accelerating these particles to unimaginable speeds. These winds, moving at half the speed of light, might not only shape entire galaxies but also fling atomic nuclei across the cosmos with incredible energy.

The universe is full of different types of radiation and particles that can be observed here on Earth. This includes photons across the entire range of the electromagnetic spectrum, from the lowest radio frequencies all the way to the highest-energy gamma rays. It also includes other particles such as neutrinos and cosmic rays, which race through the universe at close to the speed of light.