In recent years, NASA’s Parker Solar Probe has given us a close-up look at the sun. Among the probe’s revelations was the presence of numerous kinks, or “switchbacks,” in magnetic field lines in the sun’s outer atmosphere. These switchbacks are thought to form when solar magnetic field lines that point in opposite directions break and then snap together, or “reconnect,” in a new arrangement, leaving telltale zigzag kinks in the reconfigured lines.

In their article published in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics, E. O. McDougall and M. R. Argall now report observations of a switchback-shaped structure in Earth’s magnetic field, suggesting that switchbacks can also form near planets.

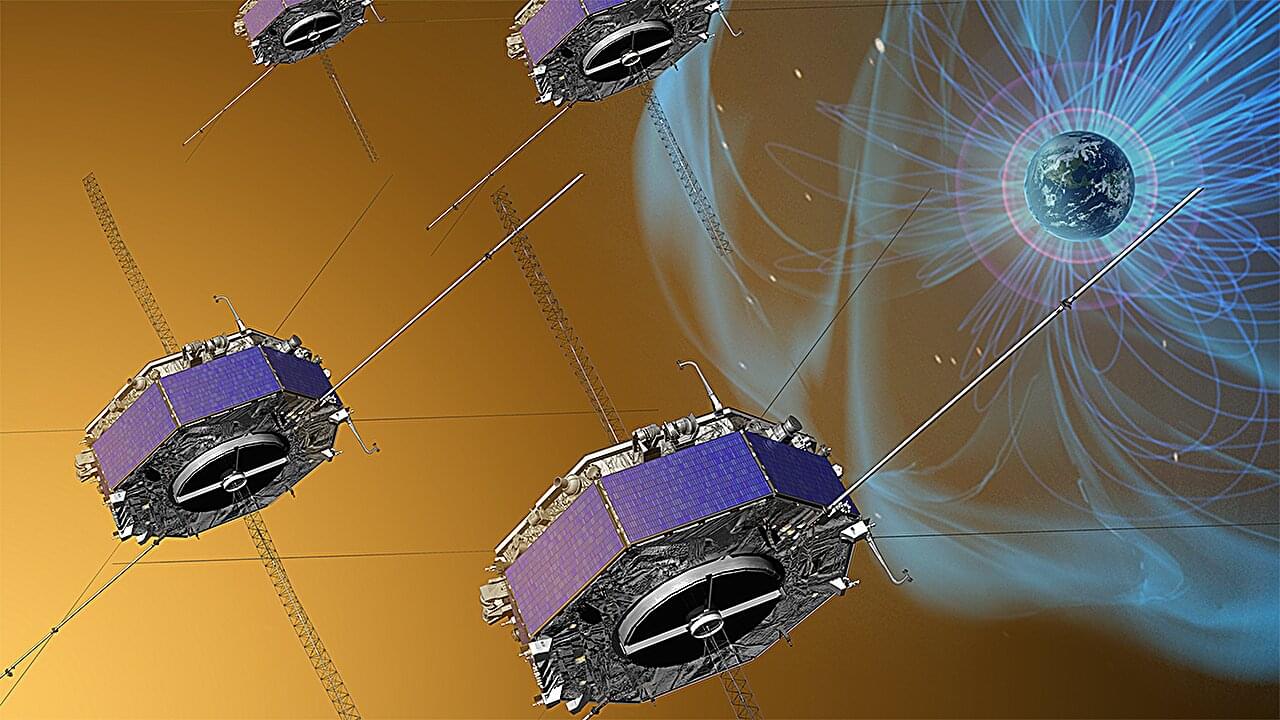

The researchers discovered the switchback while analyzing data from NASA’s Magnetospheric Multiscale mission, which uses four Earth-orbiting satellites to study Earth’s magnetic field. They detected a twisting disturbance in the outer part of Earth’s magnetosphere—the bubble of space surrounding our planet where a cocktail of charged particles known as plasma is pushed and pulled along Earth’s magnetic field lines.