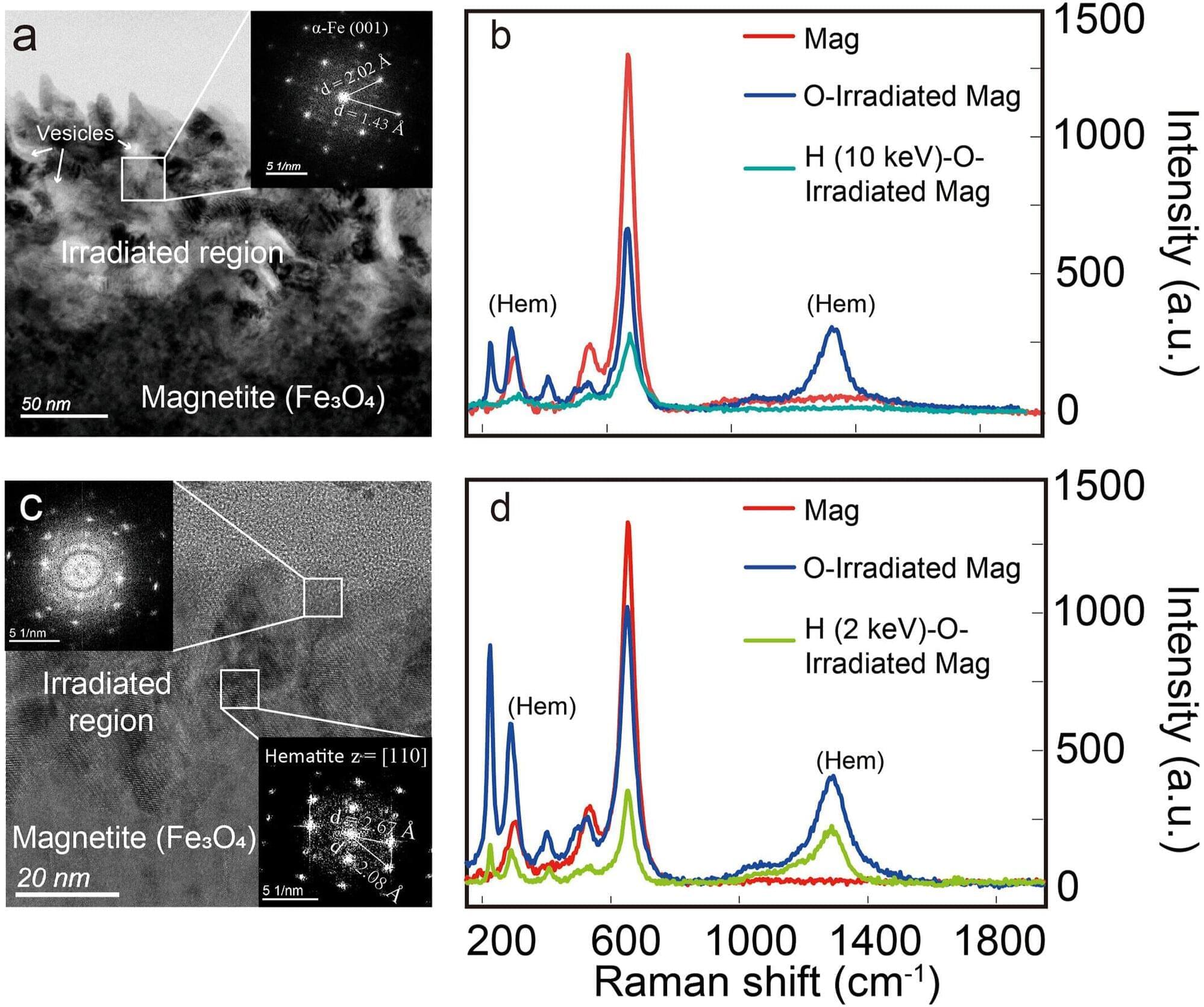

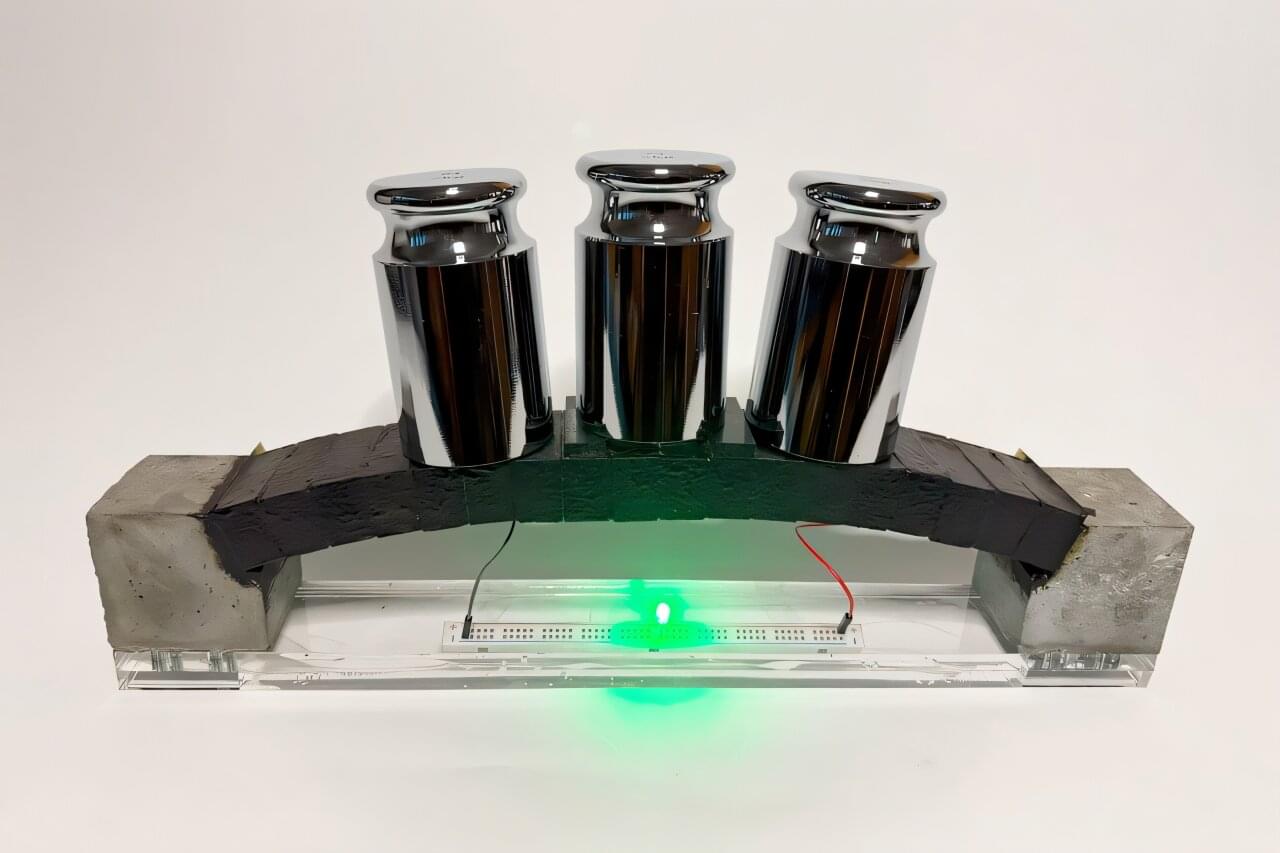

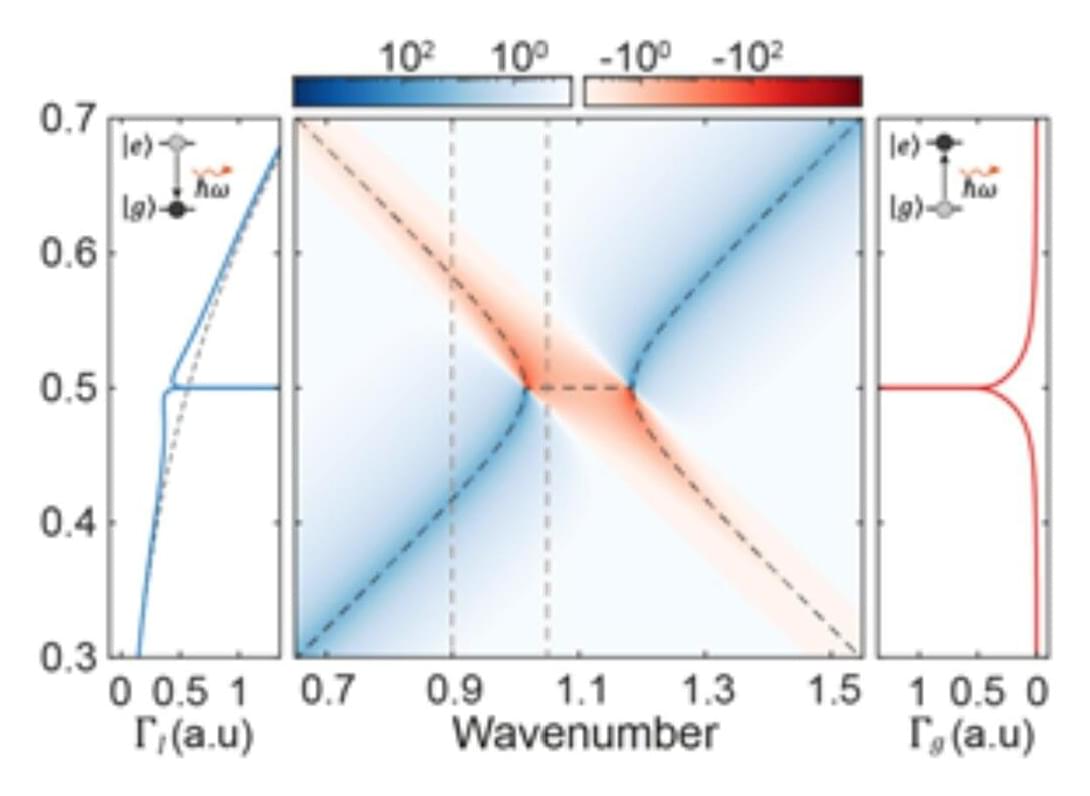

A new study reveals that spontaneous emission, a key phenomenon in the interaction between light and atoms, manifests in a new form within a photonic time crystal. This research, led by a KAIST team, not only overturns existing theory but further predicts a novel phenomenon: spontaneous emission excitation. The findings are published in the journal Physical Review Letters.

Professor Bumki Min’s research team from the KAIST Department of Physics, in collaboration with Professor Jonghwa Shin of the Department of Materials Science and Engineering, Professor Wonju Jeon of the Department of Mechanical Engineering, Professor Gil Young Cho of the Department of Physics, and researchers from IBS, UC Berkeley, and the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, announced that they have proven that the spontaneous emission decay rate in a photonic time crystal is, on the contrary, enhanced rather than being “extinguished,” as suggested by a paper published in Science in 2022. Furthermore, they predicted a new process—spontaneous emission excitation—where an atom transitions from its ground state to an excited state while simultaneously emitting a photon.

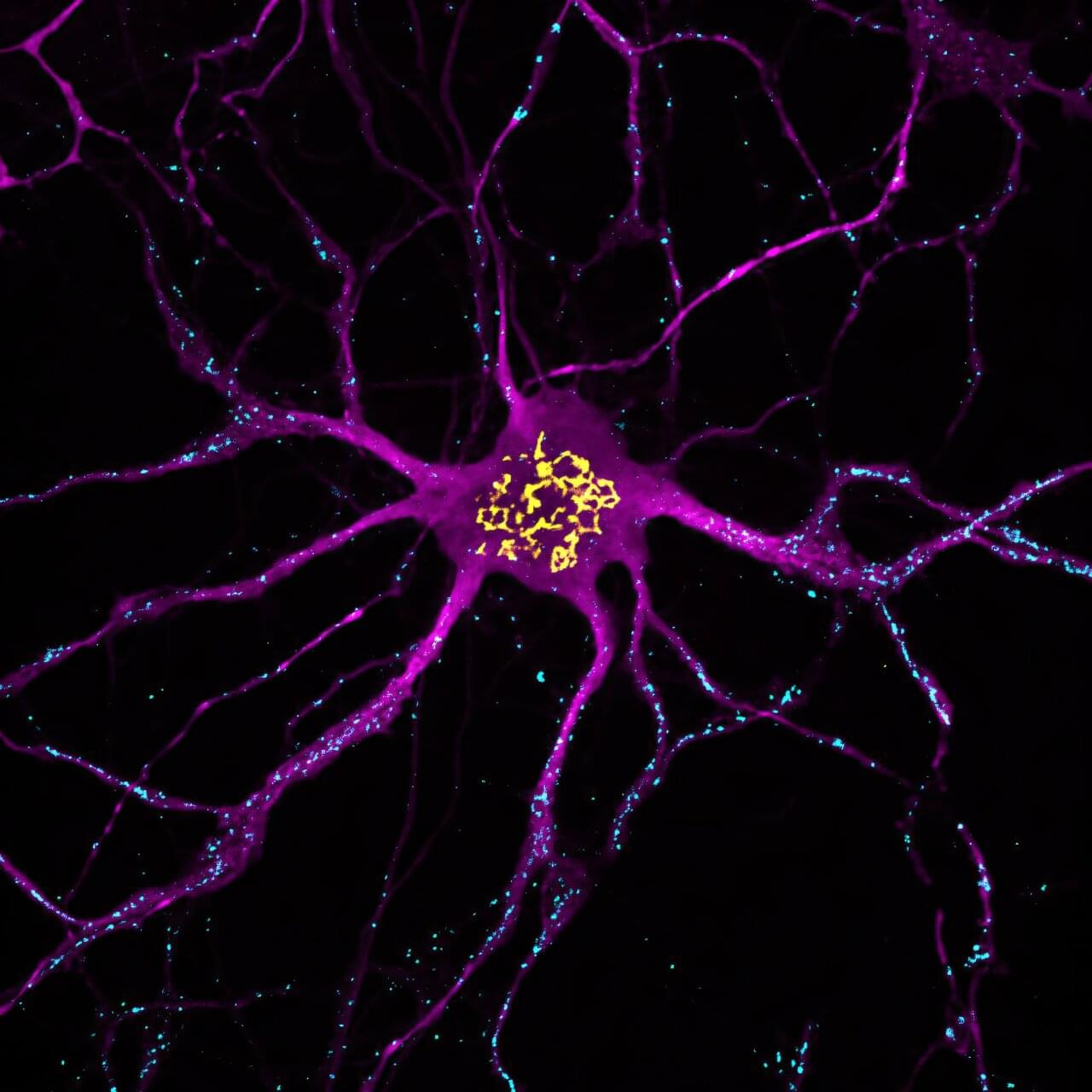

Spontaneous emission is the process by which an atom intrinsically emits a photon and is fundamental to quantum optics and photonic device research. Until now, control over spontaneous emission has been achieved by designing spatial structures like resonators or photonic crystals. However, the advent of photonic time crystals, which periodically modulate the refractive index of a medium over time, has drawn attention to the potential for control along the time axis.