Imagine zooming into matter at the quantum scale, where tiny particles can interact in more than a trillion configurations at once.

The 2025 Nobel Prize in Physics recognizes the discovery of macroscopic quantum tunneling in electrical circuits.

This story will be updated with a longer explanation of the Nobel-winning work on Thursday, 9 October.

Running up against a barrier, a classical object bounces back, but a quantum particle can come out the other side. So-called quantum tunneling explains a host of phenomena, from electron jumps in semiconductors to radioactive decays in nuclei. But tunneling is not limited to subatomic particles, as underscored by this year’s Nobel Prize in Physics. The prize recipients—John Clarke from the University of California, Berkeley; Michel Devoret from Yale University; and John Martinis from the University of California, Santa Barbara—demonstrated that large objects consisting of billions of particles can also tunnel across barriers [1– 3]. Using a superconducting circuit, the physicists showed that the superconducting electrons, acting as a collective unit, tunneled across an energy barrier between two voltage states. The work thrust open the field of superconducting circuits, which have become one of the promising platforms for future quantum computing devices.

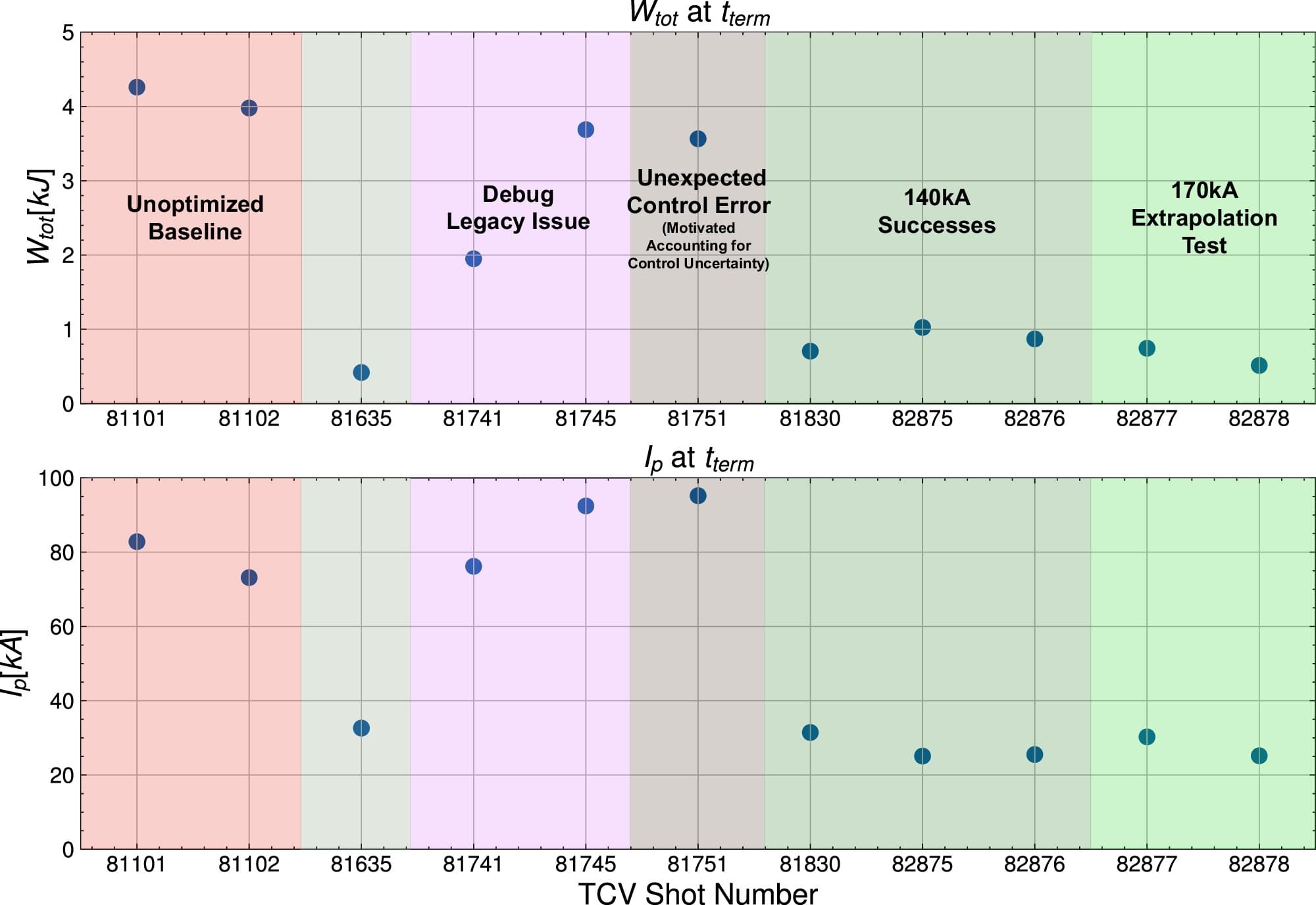

Tokamaks are machines that are meant to hold and harness the power of the sun. These fusion machines use powerful magnets to contain a plasma hotter than the sun’s core and push the plasma’s atoms to fuse and release energy. If tokamaks can operate safely and efficiently, the machines could one day provide clean and limitless fusion energy.

Today, there are a number of experimental tokamaks in operation around the world, with more underway. Most are small-scale research machines built to investigate how the devices can spin up plasma and harness its energy.

One of the challenges that tokamaks face is how to safely and reliably turn off a plasma current that is circulating at speeds of up to 100 kilometers per second, at temperatures of over 100 million degrees Celsius.

Neutrinos are very common fundamental particles included in the Standard Model of particle physics. Measuring their properties allows for creating more accurate models of the birth of the universe, the life of stars and the interactions between fundamental particles. Some of the open questions include the absolute mass of the neutrino and whether neutrinos are their own antiparticles.

“The mass and the antiparticle nature of neutrinos can be studied by measuring the radioactive beta and double-beta decays of atomic nuclei. There are likely some tens of suitable nuclei for such studies. The energy released in the decay, called the Q value, affects whether a nucleus can be used in the studies,” says Doctoral Researcher Jouni Ruotsalainen from the University of Jyväskylä, Finland.

The amplituhedron is a geometric shape with an almost mystical quality: Compute its volume, and you get the answer to a central calculation in physics about how particles interact.

Now, a young mathematician at Cornell University named Pavel (Pasha) Galashin has found that the amplituhedron is also mysteriously connected to another completely unrelated subject: origami, the art of paper folding. In a proof posted in October 2024, he showed that patterns that arise in origami can be translated into a set of points that together form the amplituhedron. Somehow, the way paper folds and the way particles collide produce the same geometric shape.

“Pasha has done some brilliant work related to the amplituhedron before,” said Nima Arkani-Hamed, a physicist at the Institute for Advanced Study who introduced the amplituhedron in 2013 with his graduate student at the time, Jaroslav Trnka. “But this is next-level stuff for me.”

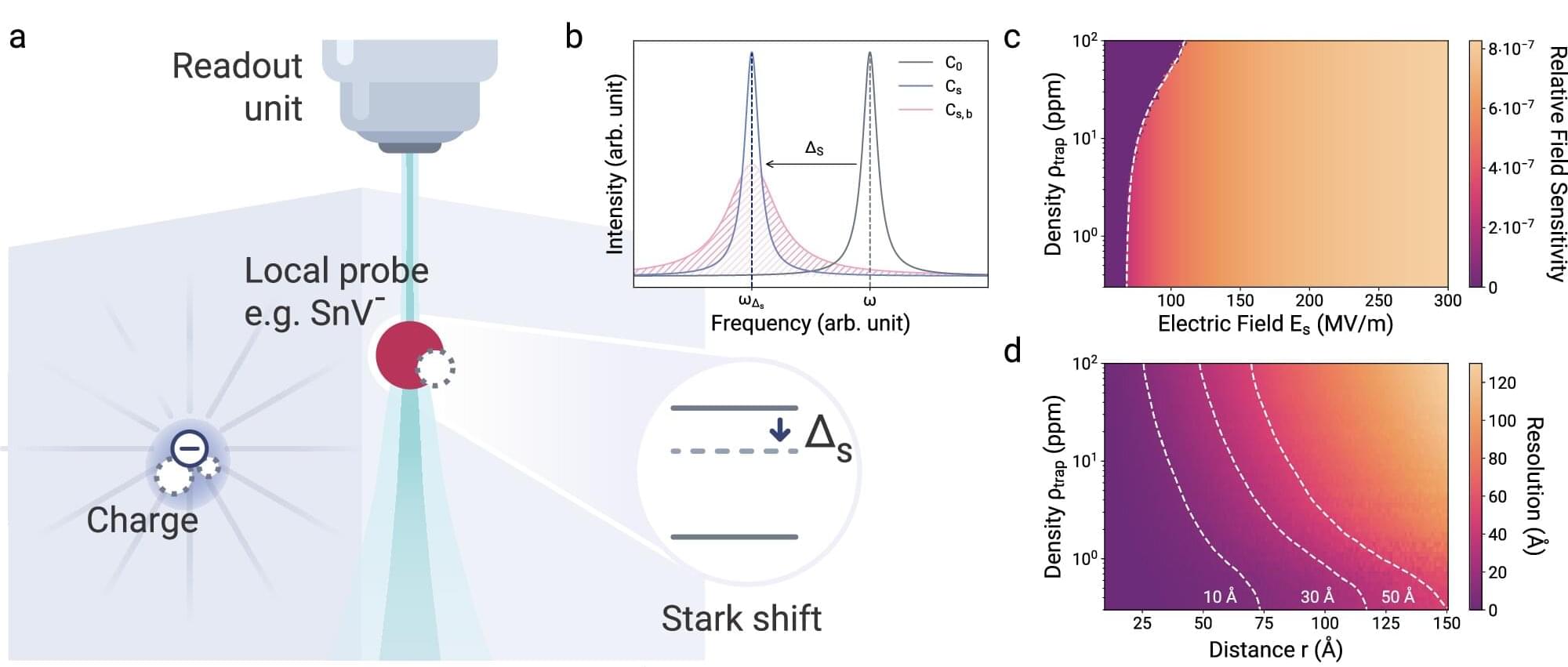

From computer chips to quantum dots—technological platforms were only made possible thanks to a detailed understanding of the used solid-state materials, such as silicon or more complex semiconductor materials. This understanding also includes being able to identify and control irregularities in the crystal lattice of such materials.

If, for example, an atom is missing in the lattice structure of the crystals, a single electron and thus an electric charge can become trapped there. Such charge traps generate electromagnetic noise that limits the functionality of these materials. However, it is extremely difficult to locate these charge traps on an atomic scale.

Researchers from the “Integrated Quantum Photonics” group at the Department of Physics at Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin (HU) and the “Joint Lab Diamond Nanophotonics” at the Ferdinand-Braun-Institut, led by Prof. Dr. Tim Schröder, have developed a new sensor that can detect such individual electrical charges more precisely than ever before.

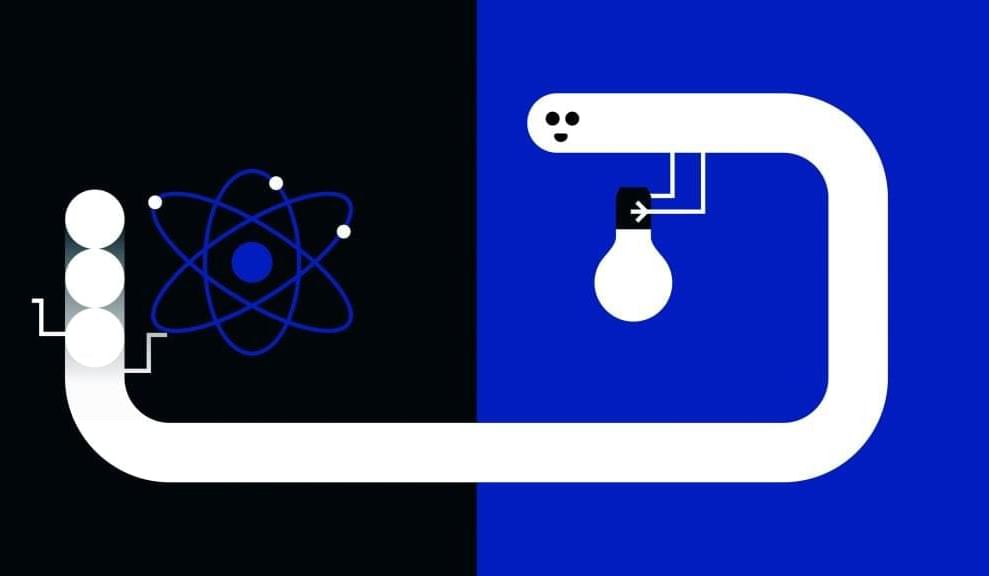

A major question in physics is the maximum size of a system that can demonstrate quantum mechanical effects. This year’s Nobel Prize laureates conducted experiments with an electrical circuit in which they demonstrated both quantum mechanical tunnelling and quantised energy levels in a system big enough to be held in the hand.

Quantum mechanics allows a particle to move straight through a barrier, using a process called tunnelling. As soon as large numbers of particles are involved, quantum mechanical effects usually become insignificant. The laureates’ experiments demonstrated that quantum mechanical properties can be made concrete on a macroscopic scale.

In 1984 and 1985, John Clarke, Michel H. Devoret and John M. Martinis conducted a series of experiments with an electronic circuit built of superconductors, components that can conduct a current with no electrical resistance. In the circuit, the superconducting components were separated by a thin layer of non-conductive material, a setup known as a Josephson junction. By refining and measuring all the various properties of their circuit, they were able to control and explore the phenomena that arose when they passed a current through it. Together, the charged particles moving through the superconductor comprised a system that behaved as if they were a single particle that filled the entire circuit.

A clever mathematical tool known as virtual particles unlocks the strange and mysterious inner workings of subatomic particles. What happens to these particles within atoms would stay unexplained without this tool. The calculations using virtual particles predict the bizarre behavior of subatomic particles with such uncanny accuracy that some scientists think “they must really exist.”

Virtual particles are not real—it says so right in their name—but if you want to understand how real particles interact with each other, they are unavoidable. They are essential tools to describe three of the forces found in nature: electromagnetism, and the strong and weak nuclear forces.

Real particles are lumps of energy that can be “seen” or detected by appropriate instruments; this feature is what makes them observable, or real. Virtual particles, on the other hand, are a sophisticated mathematical tool and cannot be seen. Physicist Richard Feynman invented them to describe the interactions between real particles.

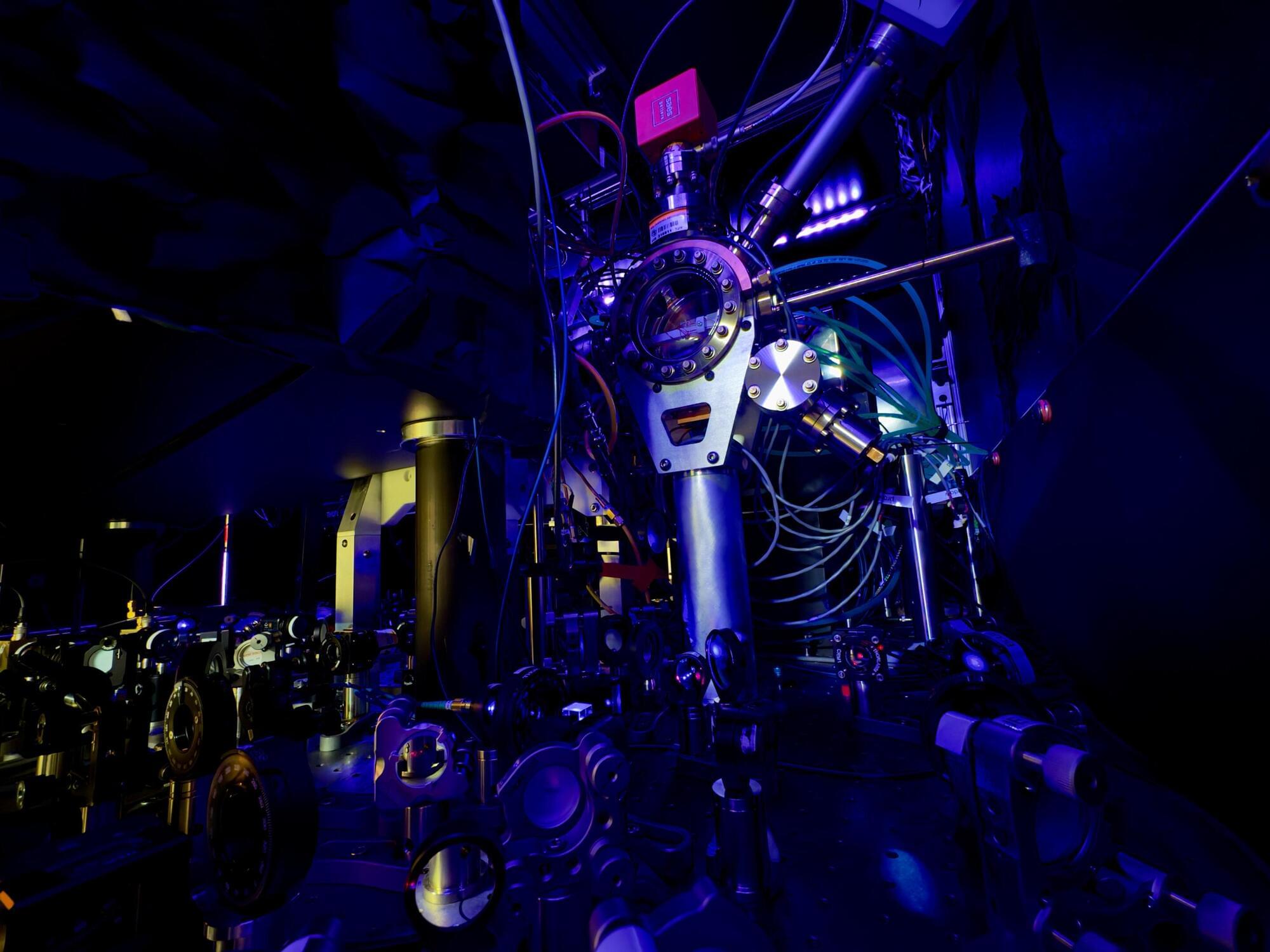

Optical lattice clocks are emerging timekeeping devices based on tens of thousands of ultracold atoms trapped in an optical lattice (i.e., a grid of laser light). By oscillating between two distinct quantum states at a particular frequency, these atoms could help to measure time with much higher precision than existing clocks, which would be highly advantageous for the study of various fundamental physical processes and systems.

Researchers at JILA, National Institute of Standards and Technology and University of Chicago recently developed an optical lattice clock based on strontium atoms that was keeping time with remarkable precision and accuracy. The new strontium optical clock, introduced in a paper published in Physical Review Letters, could open new possibilities for research aimed at testing variations in fundamental physics constants and the timing of specific physical phenomena.

“We have been pushing the performance of the optical lattice clock,” Kyungtae Kim, first author of the paper, told Phys.org. “Thanks to a major upgrade from 2019 to 2021, we demonstrated record differential frequency measurement capability, reaching a resolution of gravitational redshift below the 1-mm scale, as well as record accuracy (until this July) as a frequency standard. To push the performance further, one needs to understand and model the current system. This work provides a detailed snapshot of the clock’s current operation.”

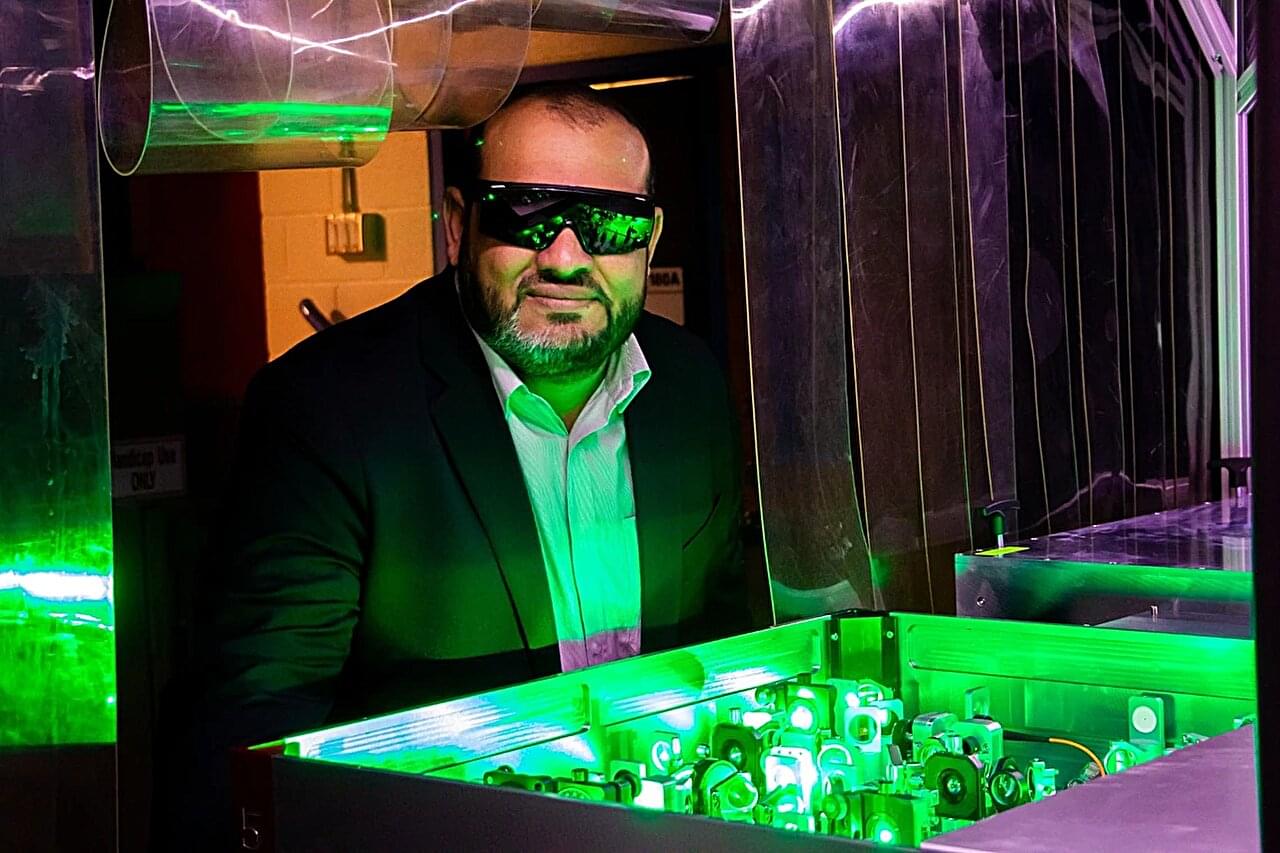

Researchers from the University of Arizona, working with an international team, have captured and controlled quantum uncertainty in real time using ultrafast pulses of light. Their discovery, published in the journal Light: Science & Applications, could lead to more secure communication and the development of ultrafast quantum optics.

At the heart of the breakthrough is “squeezed light,” said Mohammed Hassan, the paper’s corresponding author and associate professor of physics and optical sciences.

In quantum physics, light is identified by two linked properties that roughly correspond to a particle’s position and intensity—but can never be known with perfect precision, a concept known as uncertainty. The product of these two measurements cannot fall below a certain threshold, much like the fixed amount of air in a balloon, with each measurement representing one side of the balloon.