Right now, the debate about consciousness often feels frozen between two entrenched positions. On one side sits computational functionalism, which treats cognition as something you can fully explain in terms of abstract information processing: get the right functional organization (regardless of the material it runs on) and you get consciousness.

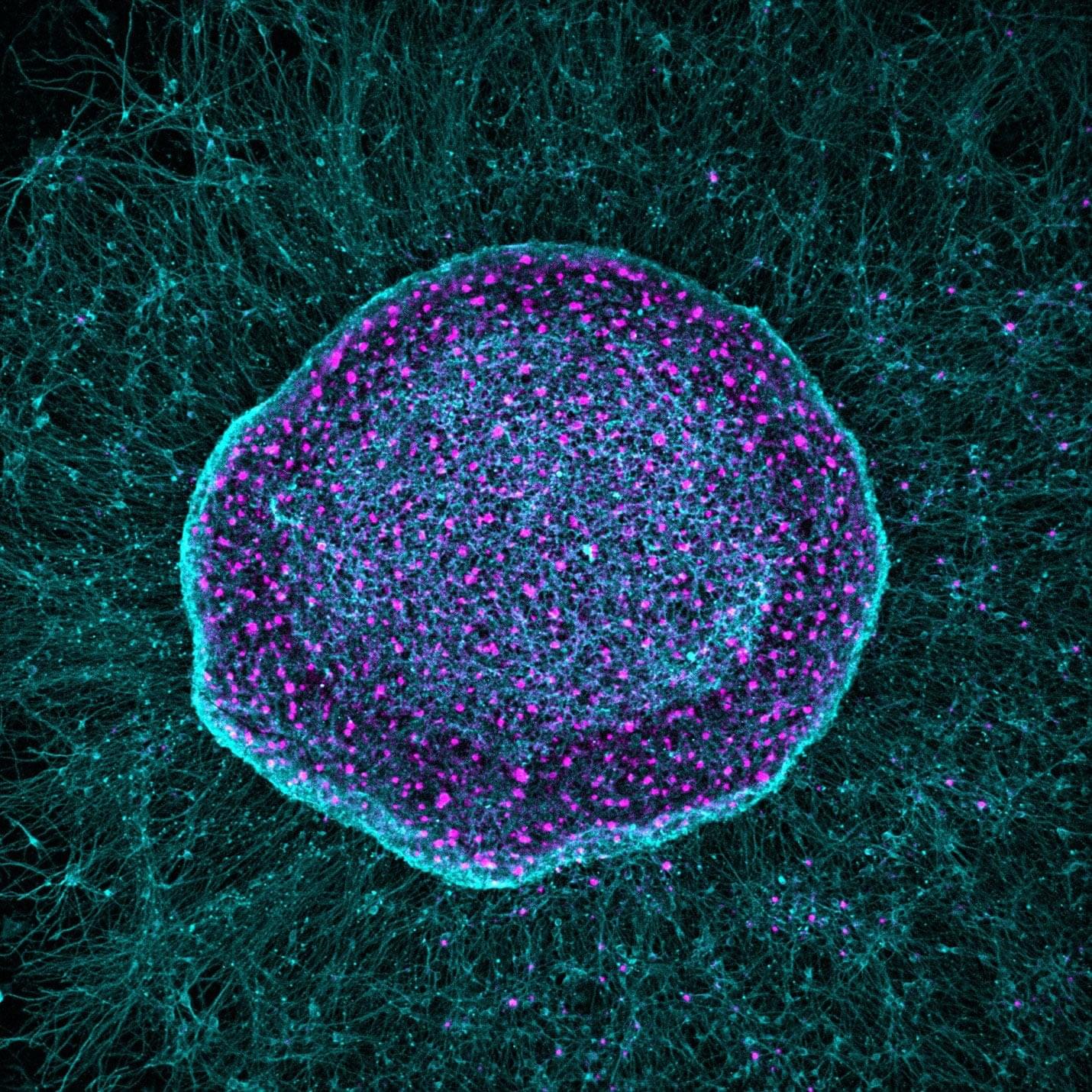

On the other hand is biological naturalism, which insists that consciousness is inseparable from the distinctive properties of living brains and bodies: biology isn’t just a vehicle for cognition, it is part of what cognition is. Each camp captures something important, but the stalemate suggests that something is missing from the picture.

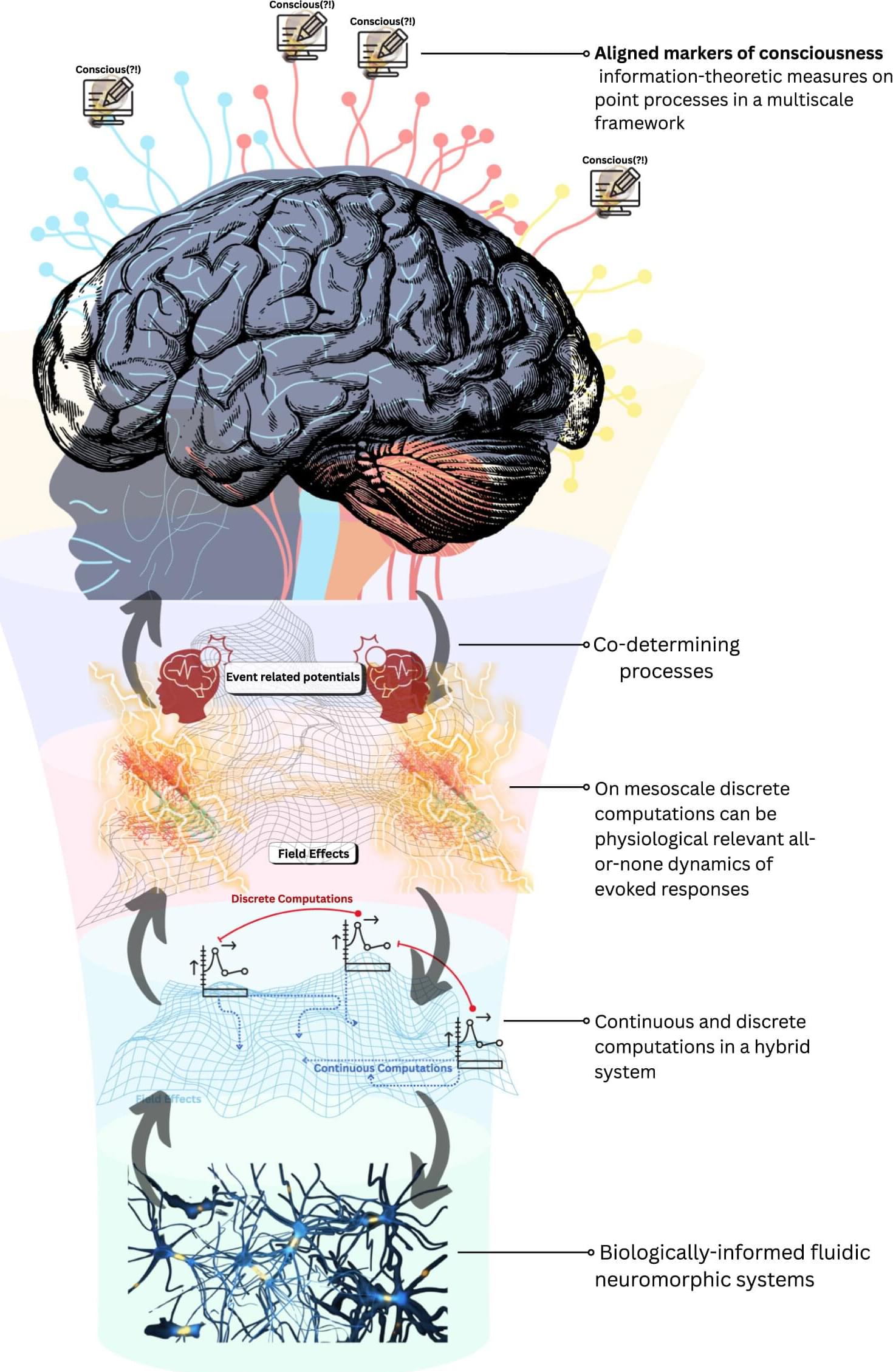

In our new paper, we argue for a third path: biological computationalism. The idea is deliberately provocative but, we think, clarifying. Our core claim is that the traditional computational paradigm is broken or at least badly mismatched to how real brains operate.