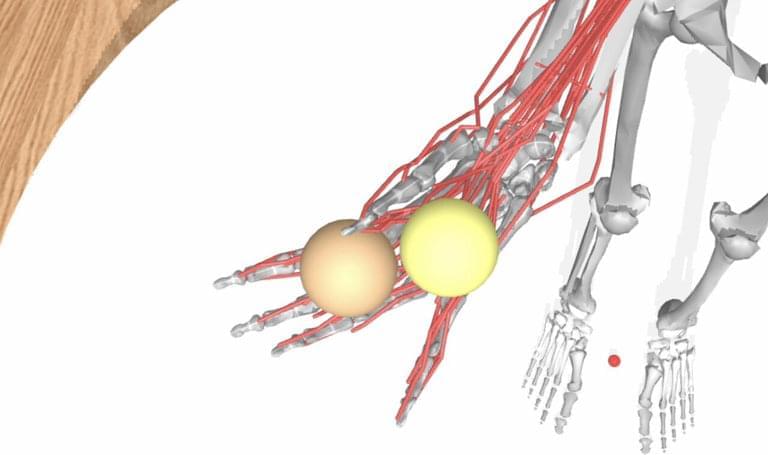

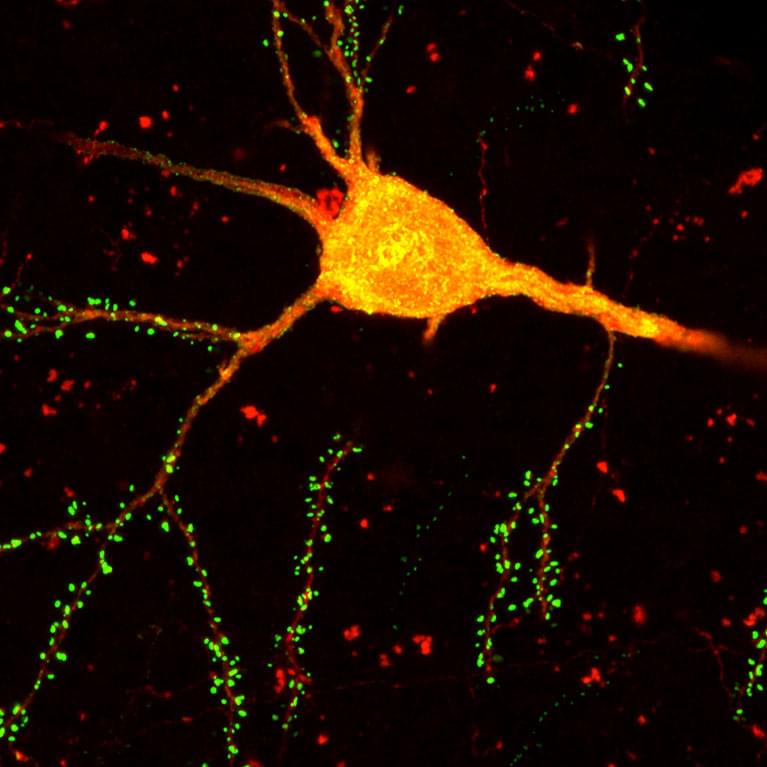

Researchers from the Color and Food Quality group at the Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Seville, in partnership with Dr. Marina Ezcurra’s team at the University of Kent (UK), have demonstrated that the carotenoid phytoene extends the lifespan of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Additionally, it delays the onset of paralysis linked to amyloid plaque formation in an Alzheimer’s disease model.

Specifically, increases in longevity of between 10 and 18.6% and decreases in the proteotoxic effect of plaques of between 30 and 40% were observed. The studies, which form part of Ángeles Morón Ortiz’s doctoral thesis, tested pure phytoene and extracts rich in this carotenoid obtained from microalgae.

According to Dr. Paula Mapelli Brahm, “These are very exciting preliminary results, so we are looking for funding to continue this line of research and to find out by what mechanisms these effects are produced.”