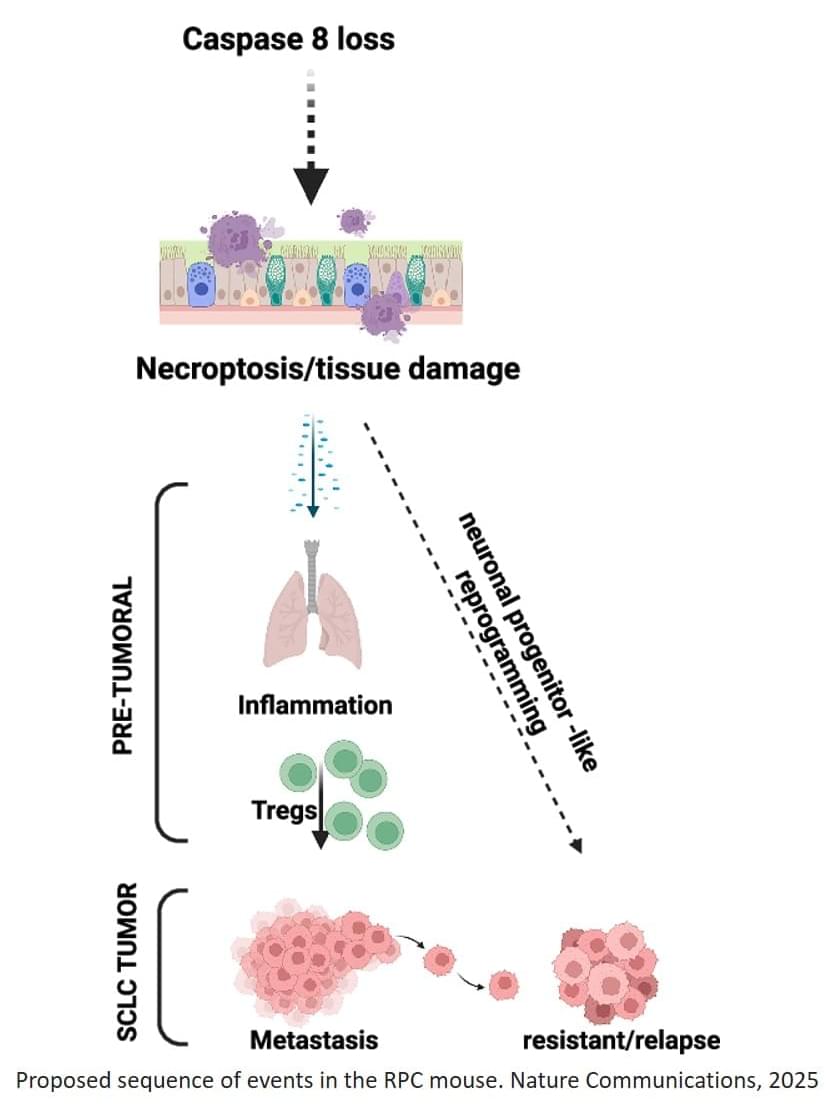

Unlike other epithelial cancers, small cell lung cancer (SCLC) shares features with neuronal cells, including lack of caspase-8 expression, a protein involved in programmed, non-inflammatory cell-death (apoptosis), a mechanism that is essential to eliminate faulty or mutated cells and to maintain health.

To better mimic the features of human SCLC, the team generated and characterized a novel genetically engineered mouse model lacking caspase-8. Using this new model, the team observed that when this protein is missing, an unusual chain reaction sets off.

“The absence of caspase-8 leads to a type of inflammatory cell death called necroptosis that creates a hostile, inflamed environment even before tumors fully form” explains the senior author. “We were also intrigued to find that pre-tumoral necroptosis can in fact promote cancer by conditioning the immune system,” the author continues.

The inflammation creates an environment where the body’s anti-cancer immune response is suppressed, preventing immune cells from attacking threats like cancer cells. This, in turn, can promote tumor metastasis. Surprisingly, the researchers observed that this inflammation also pushes the cancer cells to behave more like immature neuron-like cells, a state that makes them better at spreading and that is associated with relapse.

While it remains unknown whether similar pre-tumoral inflammation also occurs in human patients, this work identifies a mechanism contributing to the aggressiveness and patient relapse in SCLC that could be exploited as a way to improve the efficiency of future therapies and early-stage diagnostic methods. ScienceMission sciencenewshighlights.

Small cell lung cancer (SCLC) is one of the most aggressive forms of lung cancer, with a five-year survival rate of only five percent. Despite this poor prognosis, SCLC is initially highly responsive to chemotherapy. However, patients typically relapse and experience very rapid disease progression. Current research into the biological mechanisms behind SCLC remains essential in order to prolong treatment responses, overcome relapse and, ultimately, improve long-term patient outcomes.