Significance.

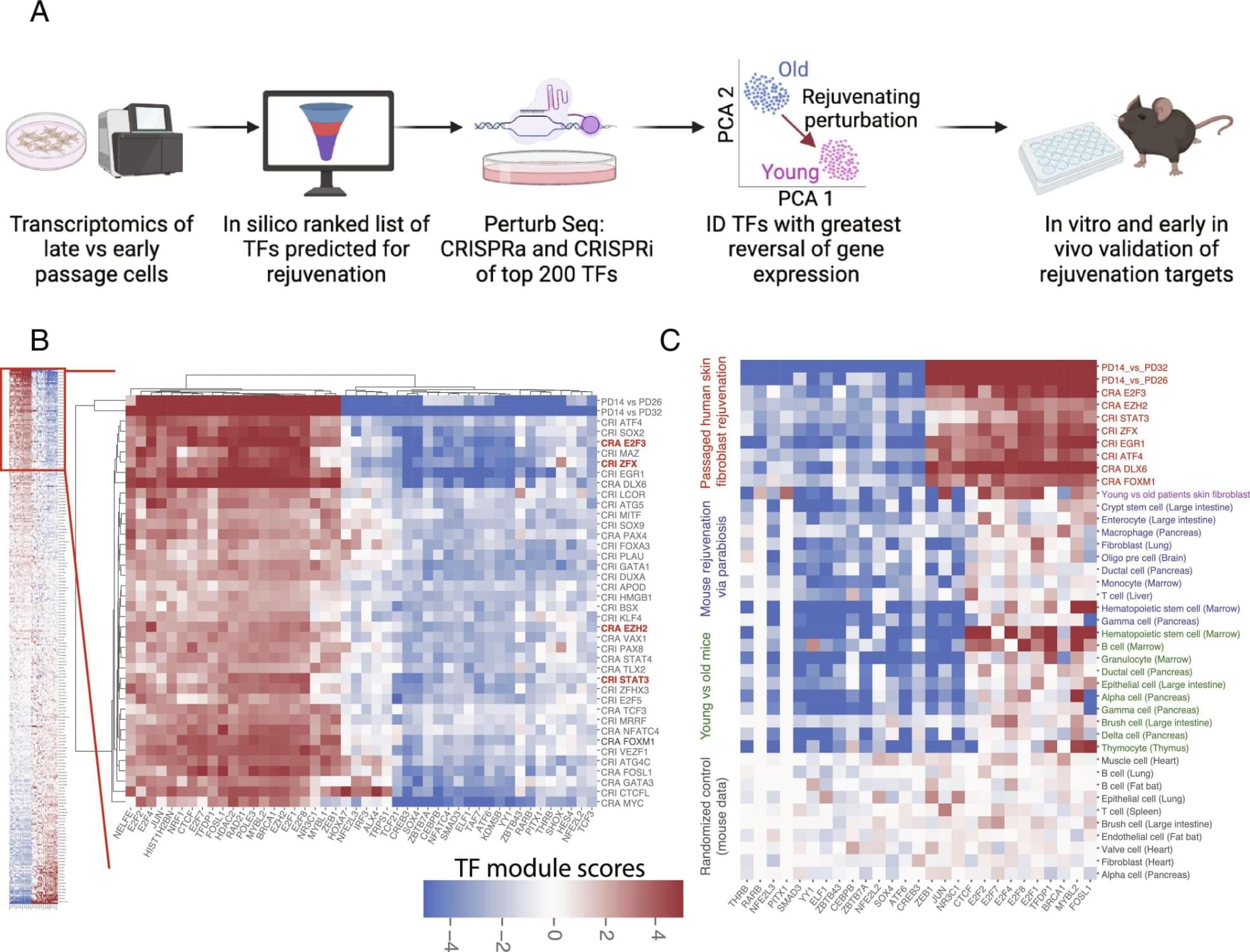

Cellular rejuvenation through transcriptional reprogramming has emerged as exciting approach to counter aging. However, to date, only a few of rejuvenating transcription factor (TF) perturbations have been identified. In this work, we developed a discovery platform to systematically identify single TF perturbations that drive cellular and tissue rejuvenation. Using a classical model of human fibroblast aging, we identified more than a dozen candidate TF perturbations and validated four of them (E2F3, EZH2, STAT3, ZFX) through cellular/molecular phenotyping. At the tissue level, we demonstrate that overexpression of EZH2 alone is sufficient to rejuvenate the liver in aged mice, significantly reducing fibrosis and steatosis, and improving glucose tolerance. Our work expanded the list of candidate rejuvenating TFs for future translation. Abstract.

Cellular rejuvenation through transcriptional reprogramming is an exciting approach to counter aging. Using a fibroblast-based model of human cell aging and Perturb-seq screening, we developed a systematic approach to identify single transcription factor (TF) perturbations that promote rejuvenation without dedifferentiation. Overexpressing E2F3 or EZH2, and repressing STAT3 or ZFX, reversed cellular hallmarks of aging—increasing proliferation, proteostasis, and mitochondrial activity, while decreasing senescence. EZH2 overexpression in vivo rejuvenated livers in aged mice, reversing aging-associated gene expression profiles, decreasing steatosis and fibrosis, and improving glucose tolerance. Mechanistically, single TF perturbations led to convergent downstream transcriptional programs conserved in different aging and rejuvenation models. These results suggest a shared set of molecular requirements for cellular and tissue rejuvenation across species. Sign up for PNAS alerts.

Get alerts for new articles, or get an alert when an article is cited. Cellular rejuvenation through transcriptional reprogramming is an exciting approach to counter aging and bring cells back to a healthy state. In both cell and animal aging models, there has been significant recent progress in rejuvenation research. Systemic factors identified in young blood through models such as heterochronic parabiosis (in which the circulatory systems of a young and aged animal are joined) rejuvenate various peripheral tissues and cognitive function in the brain (1–4). Partial reprogramming at the cellular level with the Yamanaka factors (four stem cell transcription factors) reverses cellular and tissue-level aging markers and can extend lifespan in old mice (5–8). These discoveries support the notion that transcriptional reprogramming is a powerful approach to improving the health of cells and tissues, and one day could be used as an approach for human therapeutics. However, to date, only a couple of rejuvenating transcription factor (TF) perturbations have been identified (9, 10) and most of them require the overexpression of TFs. We hypothesized that there are multiple other TF perturbations which could reset cells and tissues back to a healthier or younger state—rejuvenating them. Identifying complementary rejuvenating strategies is important as it will increase the chance of successful future translation. We developed a high-throughput platform, the Transcriptional Rejuvenation Discovery Platform (TRDP), which combines computational analysis of TF binding motifs and target predictions (Materials and Methods), global gene expression data of old and young cell states, and experimental genetic perturbations to identify which TF can restore overall gene expression and cell phenotypes to a younger, healthier state. We developed TRDP to be applicable to any cell type, and in both aging and disease settings, with the only requirements being baseline comparison of gene expression data comparing the older/diseased state to the younger/healthier state and the ability to perform genetic perturbations. To model aging in vitro as a validation of our approach, we used the canonical aging model of passaged fibroblasts (11, 12). We tested 400 TF perturbations via our screen and validated reversal of key cellular aging hallmarks in late passage human fibroblasts for four top TFs: E2F3, EZH2, STAT3, and ZFX. Moreover, EZH2 overexpression in vivo rejuvenated livers in aged mice—reversing aging-associated global gene expression profiles, significantly reducing steatosis and fibrosis, and improving glucose tolerance. These findings point to a conserved set of molecular requirements for cellular and tissue rejuvenation.