By decoding neural signals linked to a person’s inner monologue, researchers enabled communication for individuals with severe speech impairments.

Breathwork while listening to music may induce a blissful state in practitioners, accompanied by changes in blood flow to emotion-processing brain regions, according to a study published in the open-access journal PLOS One by Amy Amla Kartar from the Colasanti Lab in the Department of Clinical Neuroscience at Brighton and Sussex Medical School, U.K., and colleagues.

These changes occur even while the body’s stress response may be activated and are associated with reporting reduced negative emotions.

The popularity of breathwork as a therapeutic tool for psychological distress is rapidly expanding. Breathwork practices that increase ventilatory rate or depth, accompanied by music, can lead to altered states of consciousness (ASCs) similar to those evoked by psychedelic substances.

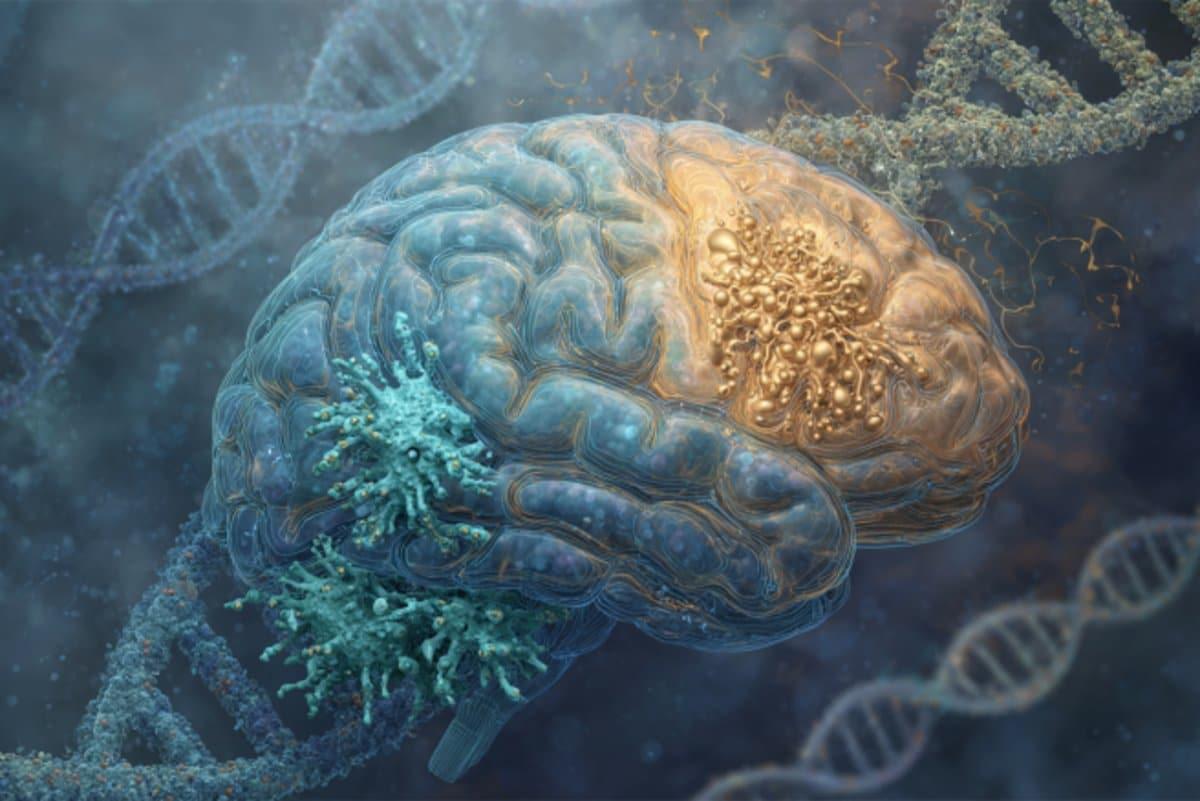

A new survey-based study suggests that the “unhappiness hump”—a widely documented rise in worry, stress, and depression with age that peaks in midlife and then declines—may have disappeared, perhaps due to declining mental health among younger people. David Blanchflower of Dartmouth College, U.S., and colleagues present these findings in the open-access journal PLOS One.

Since 2008, a U-shaped trend in well-being with age, in which well-being tends to decline from childhood until around age 50 before rebounding in old age, has been observed in developed and developing countries worldwide. Data have also revealed a corresponding “ill-being” or unhappiness hump.

Recent data point to a worldwide decline in well-being among younger people, but most studies have not directly addressed potential implications for the unhappiness hump. To help clarify, Blanchflower and colleagues first analyzed data from U.S. and U.K. surveys that included questions about participants’ mental health.

Over the past decades, engineers have introduced a wide range of computing systems inspired by the human brain or designed to emulate some of its functions. These include devices that artificially reproduce the behavior of brain cells (e.g., neurons), by processing and transmitting signals in the form of electrical pulses.

Most neuron-inspired devices developed so far use either electrons or photons to process and transmit information, rather than integrating the two. This is because photonic and electronic systems typically have very different architectures, and converting the signals they rely on can be challenging and lead to energy losses.

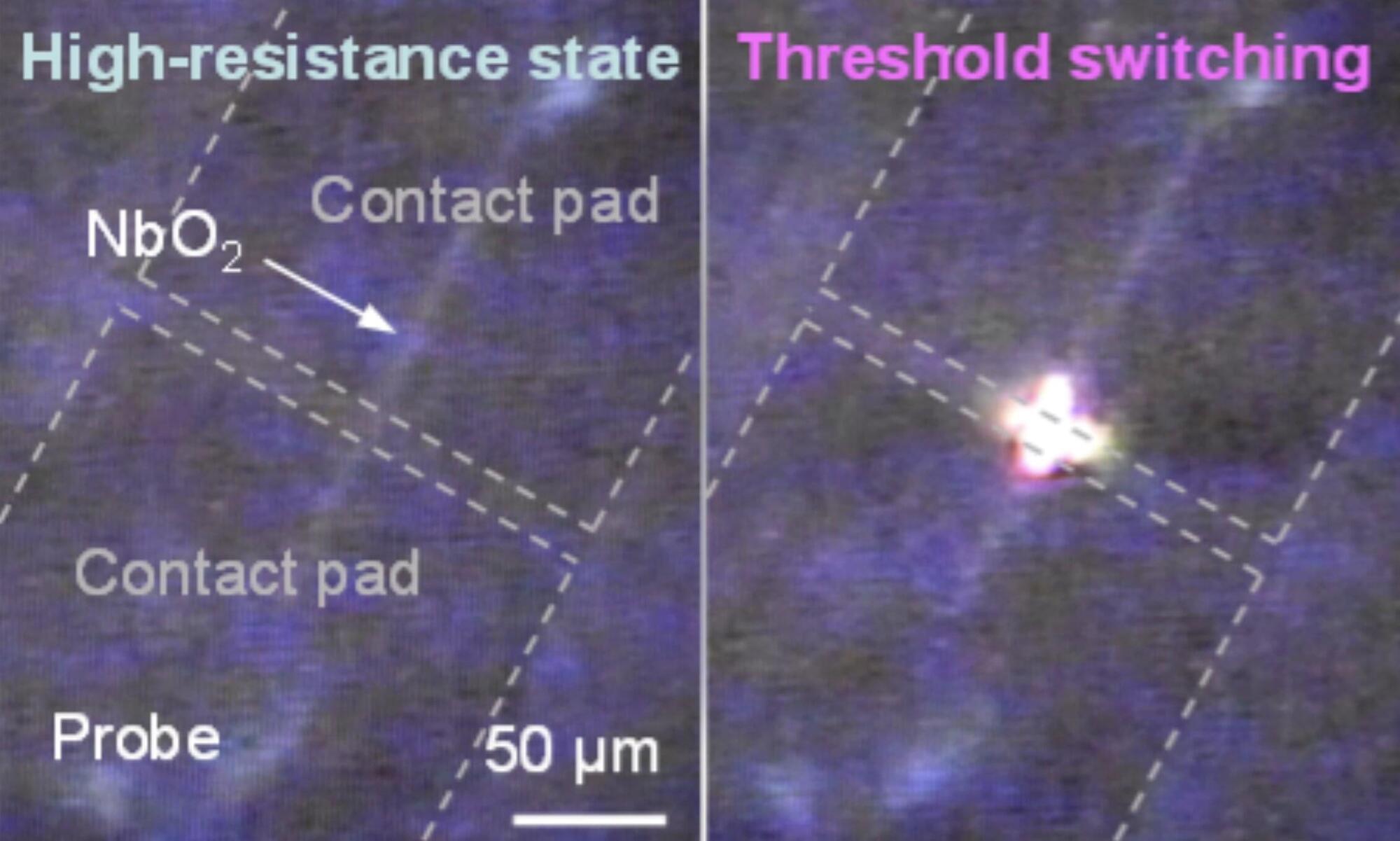

Researchers at Stanford University, Sandia National Laboratories, and Purdue University recently developed new electro–optical devices that can mimic neuron-like electrical pulses and simultaneously emit oscillating light. These devices, referred to as electro-optical Mott neurons, were introduced in a paper published in Nature Electronics.

World’s first pig lung transplant in brain-dead man lasts nine days in China.

In a medical first, a pig lung was transplanted into a brain-dead human, where it functioned for nine days.

Surgeons at Guangzhou Medical University, China, performed the cross-species lung transplantation.

The recipient, a 39-year-old man who had suffered a brain hemorrhage, received the left lung from a Chinese Bama Xiang pig that had undergone genetic modifications.

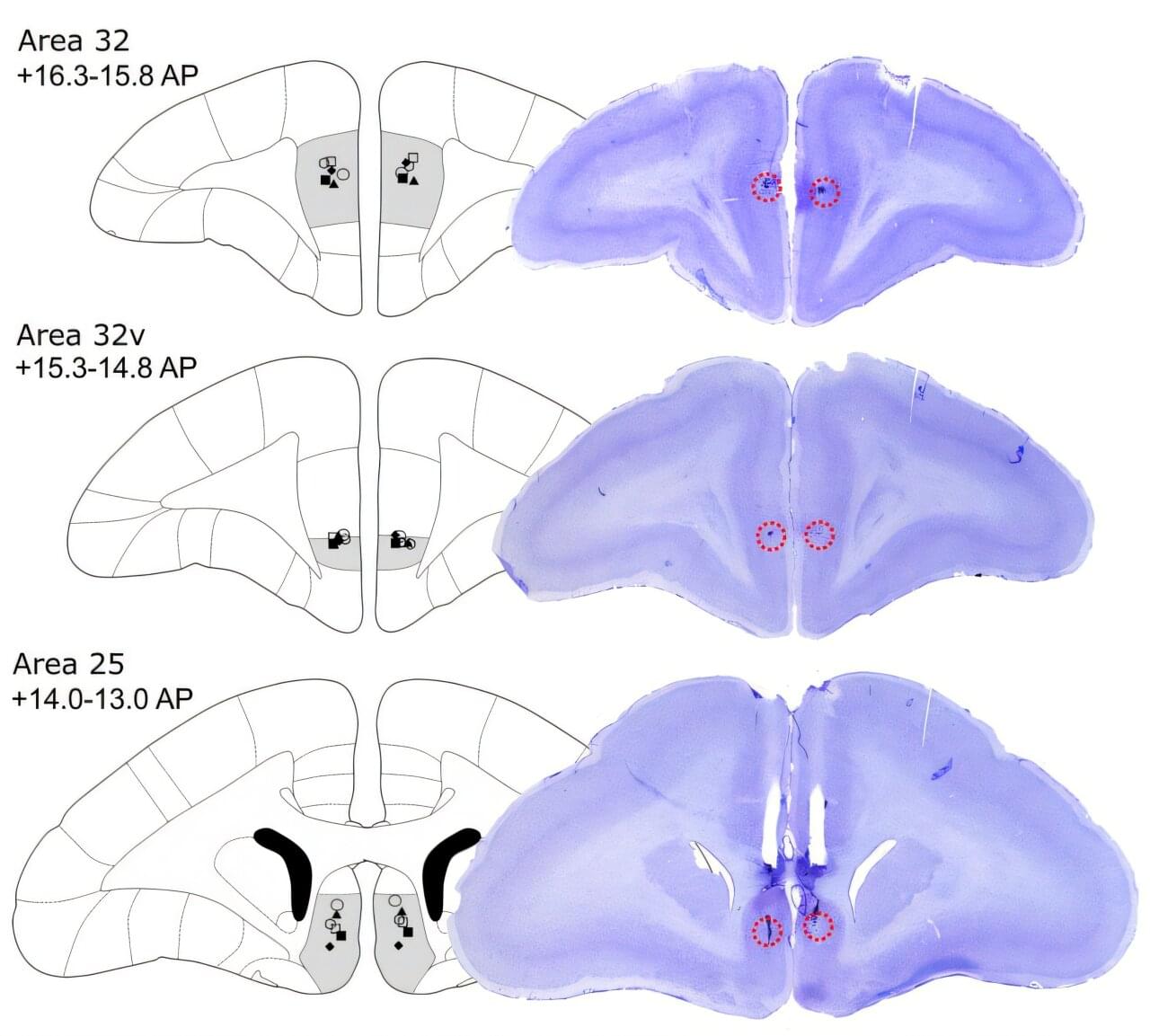

University of Cambridge researchers report that inactivating dorsolateral prefrontal cortex area 46 in marmosets blunts appetitive motivation and heightens threat reactivity, with effects mediated through asymmetric left-hemisphere pathways.

The dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC) is implicated in higher-order processes such as attention, abstract thought, working memory, and inhibitory control. It is also a target for noninvasive brain stimulation in treatment-resistant depression.

Previous studies have shown that dlPFC transcranial magnetic stimulation improves depressive and comorbid anxiety symptoms and modulates activity in subcallosal cingulate cortex area 25, a region linked to therapeutic success.

Psychotherapy leads to measurable changes in brain structure. Researchers at Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg (MLU) and the University of Münster have demonstrated this for the first time in a study in Translational Psychiatry by using cognitive behavioral therapy.

The team analyzed the brains of 30 patients suffering from acute depression. After therapy, most of them showed changes in areas responsible for processing emotions. The observed effects are similar to those already known from studies on medication.

Around 280 million people suffer from severe depression worldwide. This depression leads to changes in the brain mass of the anterior hippocampus and amygdala. Both areas are part of the limbic system and are primarily responsible for processing and controlling emotions. In psychotherapy, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is an established method for treating depression.

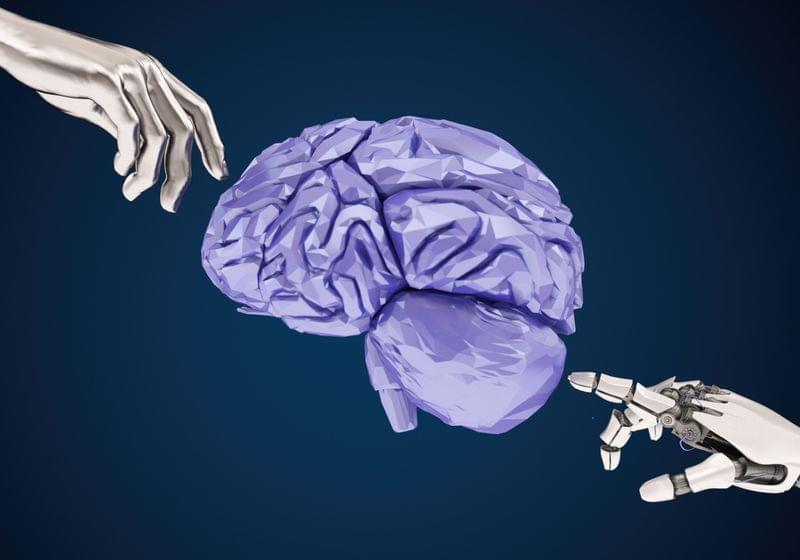

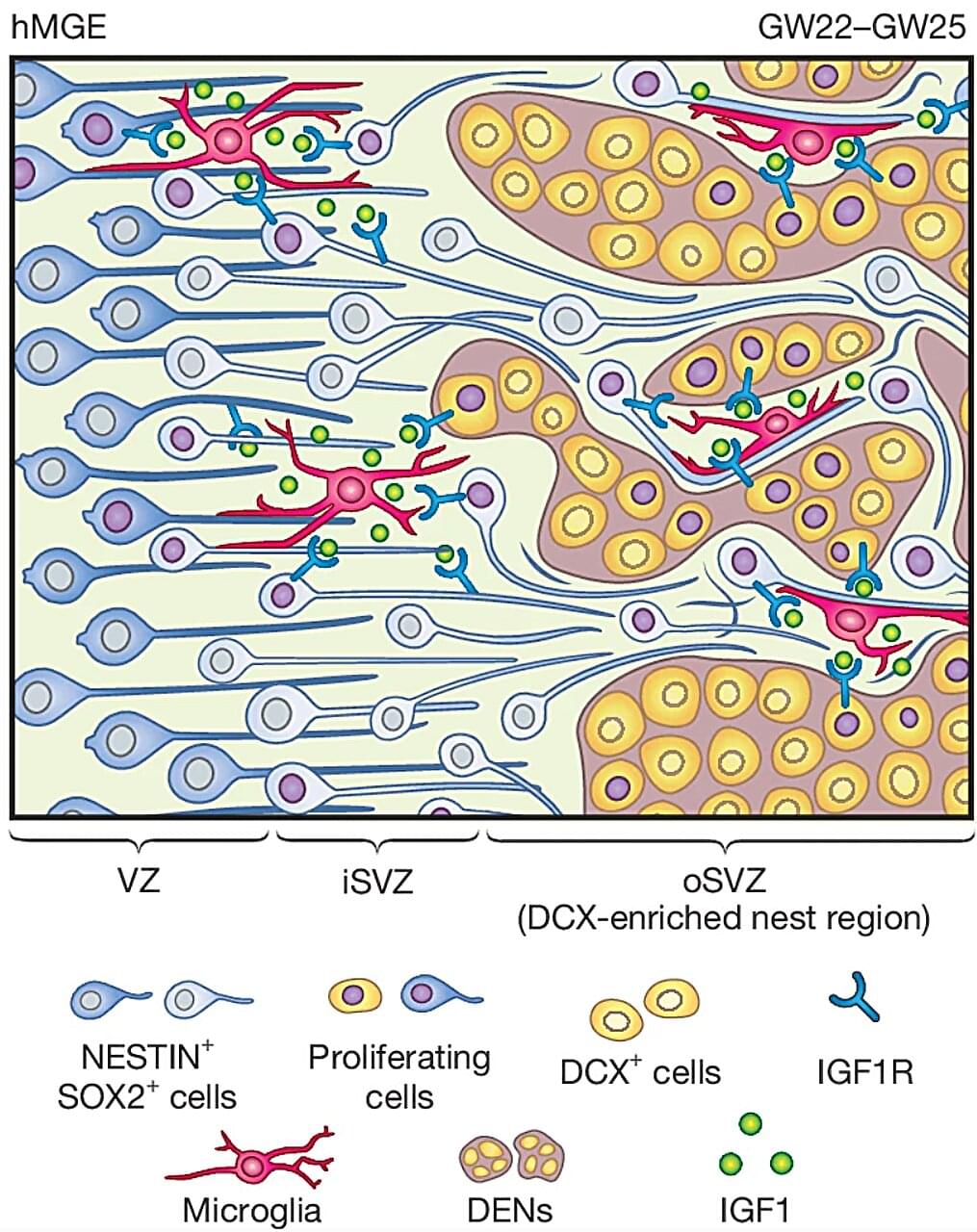

While there is a vast amount of information about the human brain and how it develops and works, much of the organ is still uncharted territory. But new research published in the journal Nature is giving us new insights into a type of brain cell called the GABAergic interneuron and its role in the developing brain. These findings could help explain how conditions like autism and brain disorders in children develop.

GABAergic interneurons are a vital part of the brain. They release the neurotransmitter gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), which regulates brain activity by switching neurons on and off. Disruptions in their functions can lead to a number of disorders, including epilepsy, schizophrenia and autism.