Functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) is a promising non-invasive neuroimaging technique that works by detecting changes in blood oxygenation linked to neural activity using near-infrared light. Compared to fMRI and various other methods commonly used to study the brain, fNIRS is easier to apply outside of laboratory settings.

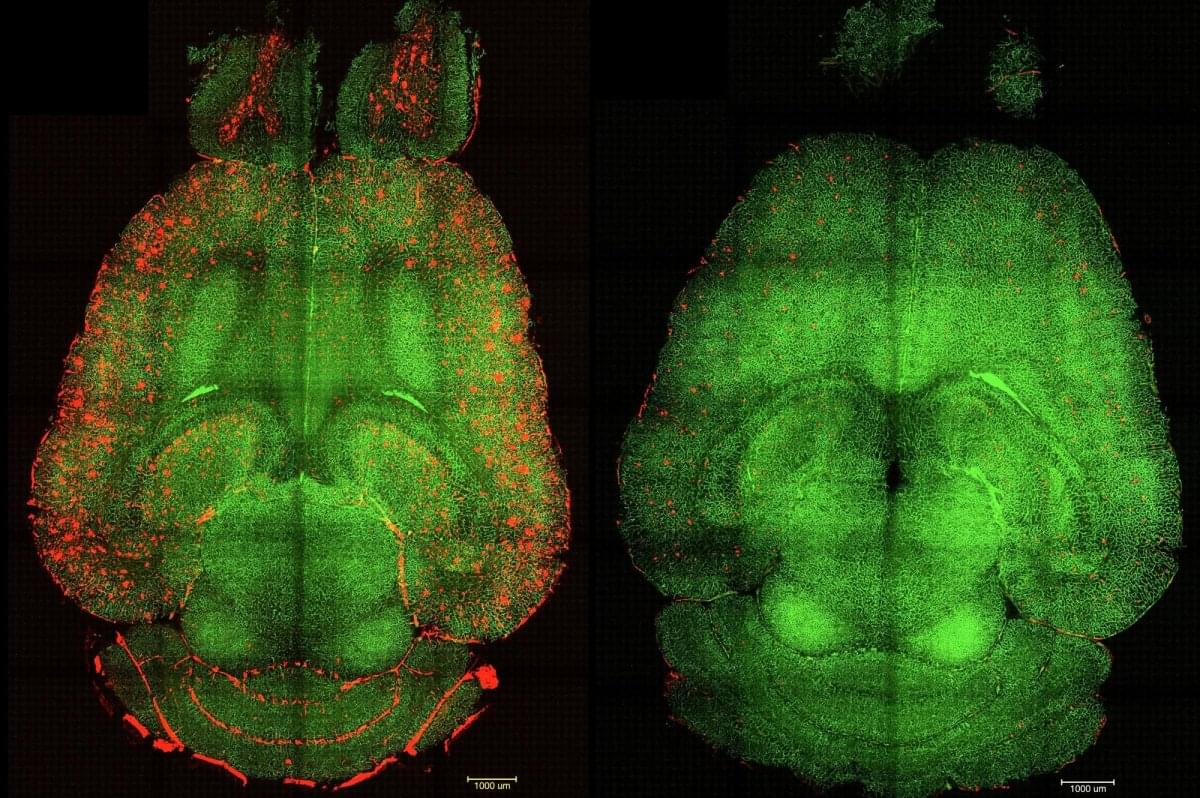

This technique requires study participants to wear a special cap fitted with optodes, which consist of light sources that emit near-infrared light into the scalp and detectors that measure the light that is reflected back. These measurements can be used to estimate blood oxygenation in the brain’s outer layers. Despite its potential for conducting research in everyday settings, the quality of signals collected using fNIRS is known to be influenced by biophysical factors.

A team of researchers at Boston University recently set out to better delineate the extent to which people’s hair and skin color, age and sex impact the quality of fNIRS signals picked up from their scalp.