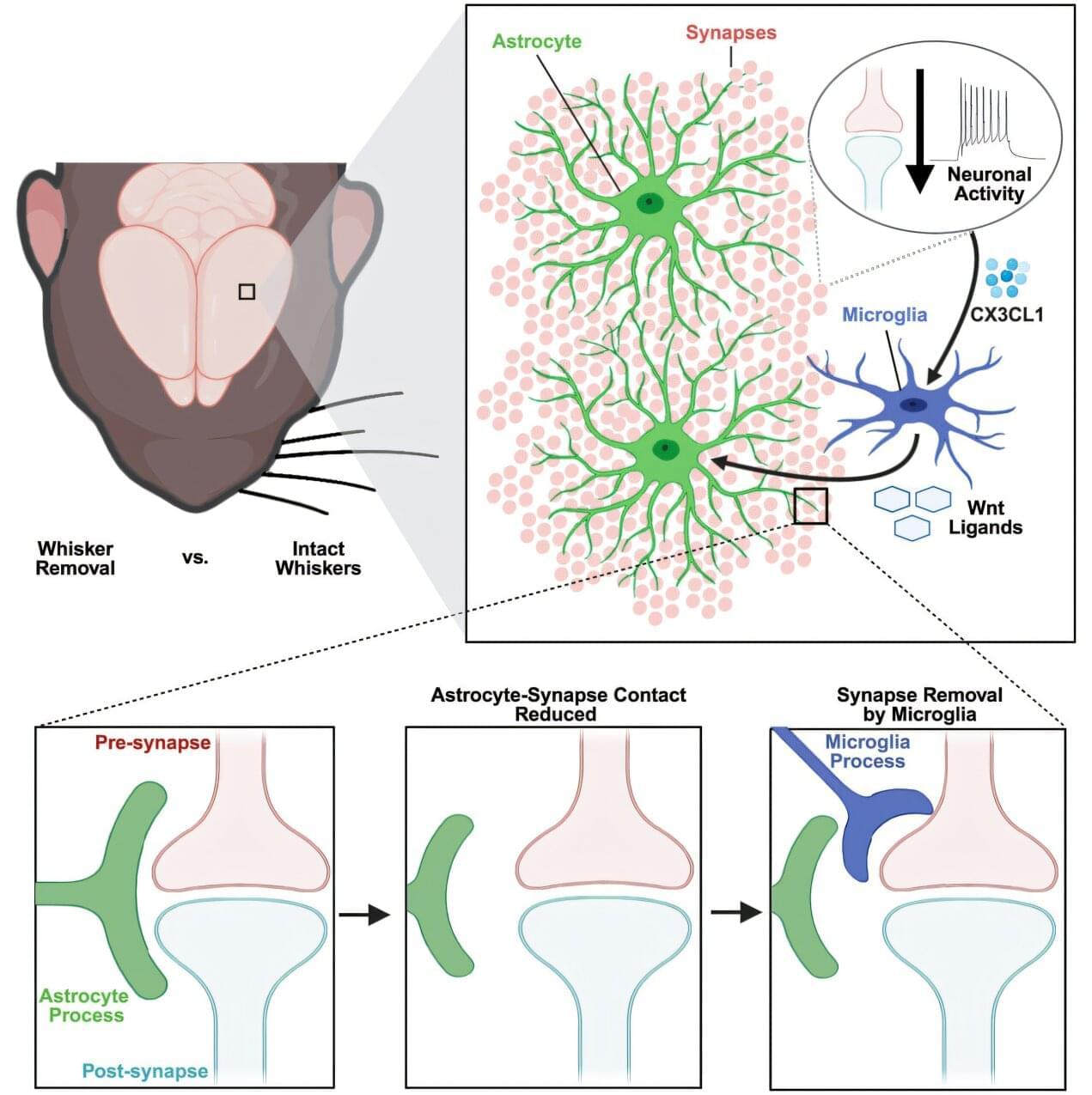

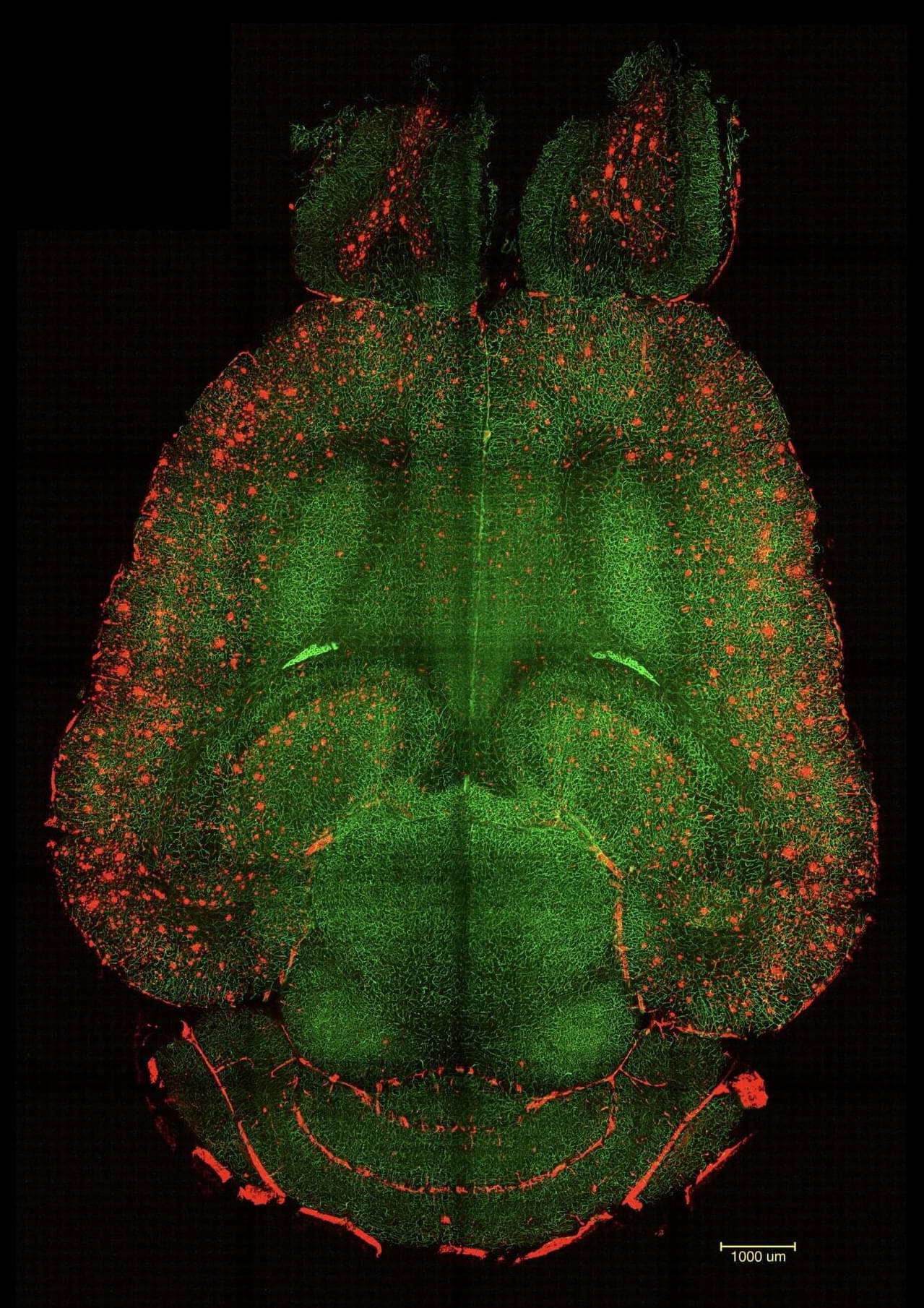

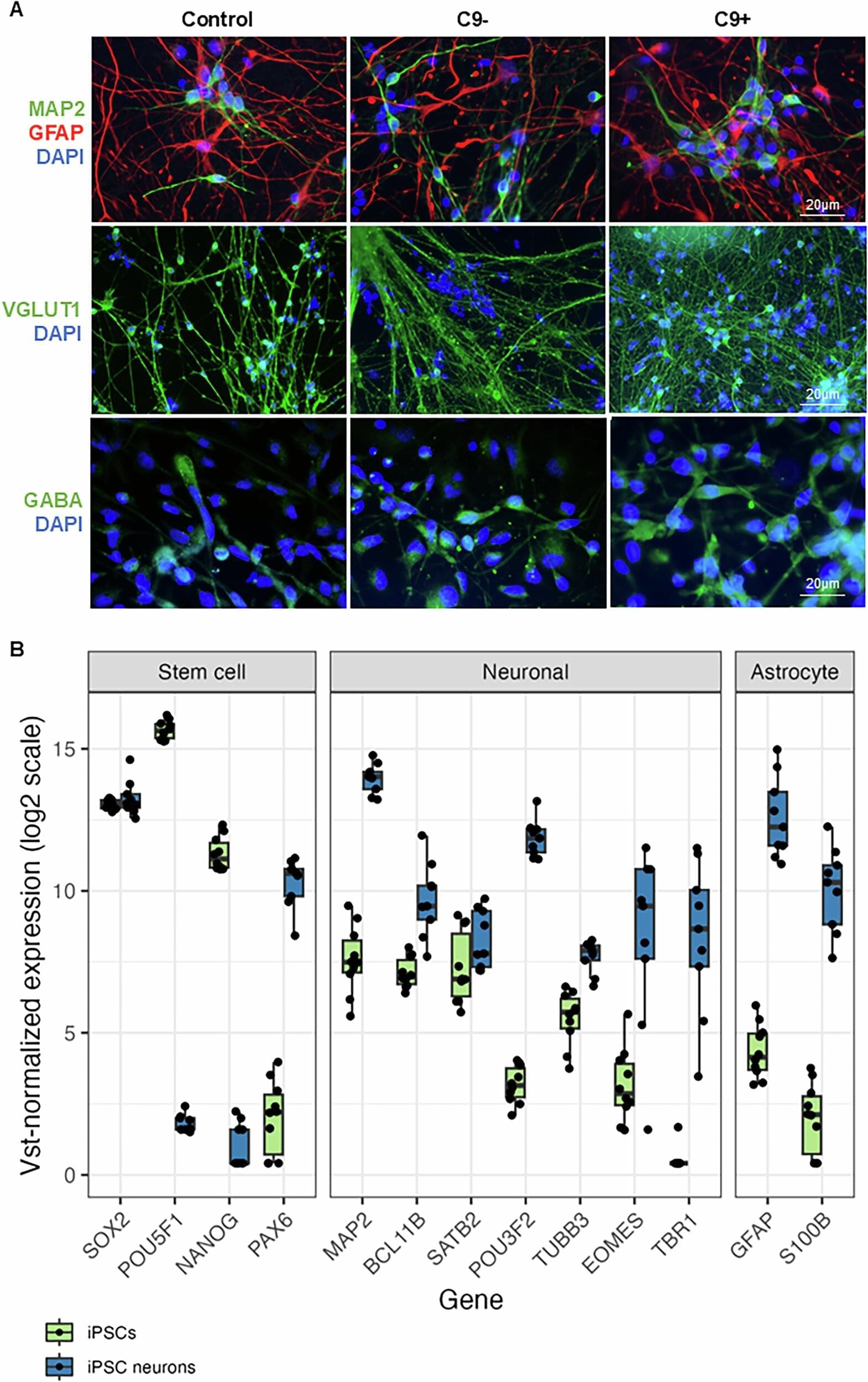

A study by Dorothy P. Schafer, Ph.D., and Travis E. Faust, Ph.D., at UMass Chan Medical School, explains how two different cell types in the brain—astrocytes and microglia—communicate in response to changes in sensory input to remodel synapses, the connections between neurons.

Published in Cell, these findings are in an emerging area of interest for neurobiologists who want to understand how different cells in the brain interact to rewire the brain.

This novel mechanism has the potential to be targeted by translational scientists hoping to one day prevent synaptic damage incurred during neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s or ALS as well as age-related cognitive decline. It may also lead to new insights into neurodevelopmental and psychiatric disorders such as autism and schizophrenia, where the brain’s circuit refinement process may have been compromised during development.