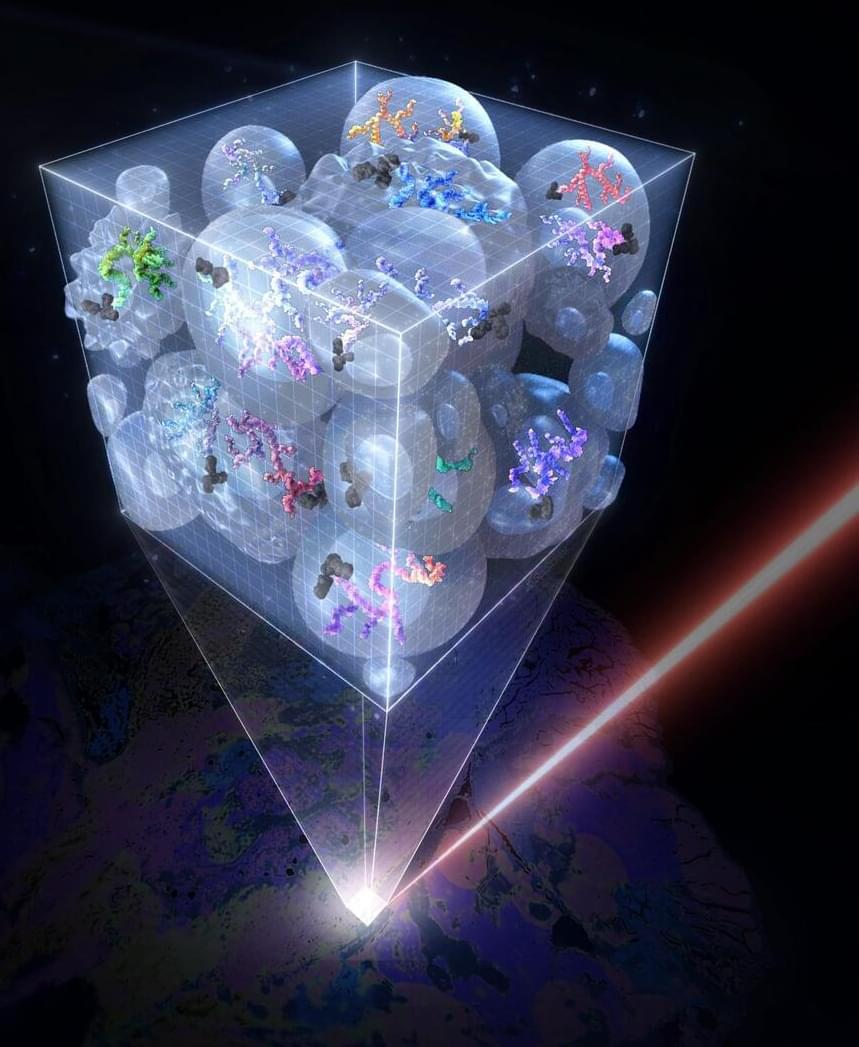

While new technologies, including those powered by artificial intelligence, provide innovative solutions to a steadily growing range of problems, these tools are only as good as the data they’re trained on. In the world of molecular biology, getting high-quality data from tiny biological systems while they’re in motion – a critical step for building next-gen tools – is something like trying to take a clear picture of a spinning propeller. Just as you need precise equipment and conditions to photograph the propeller clearly, researchers need advanced techniques and careful calculations to measure the movement of molecules accurately.

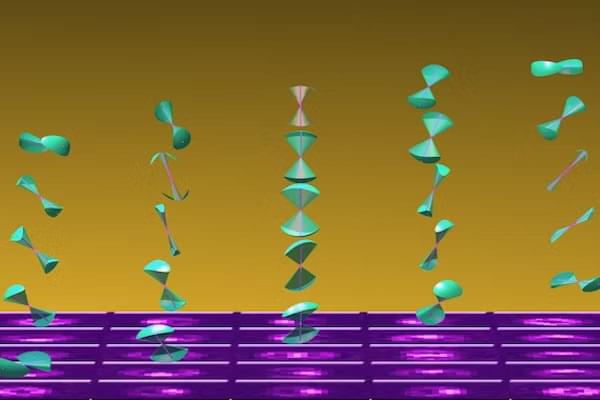

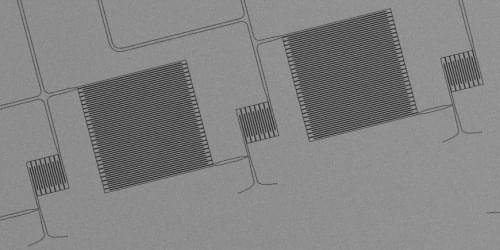

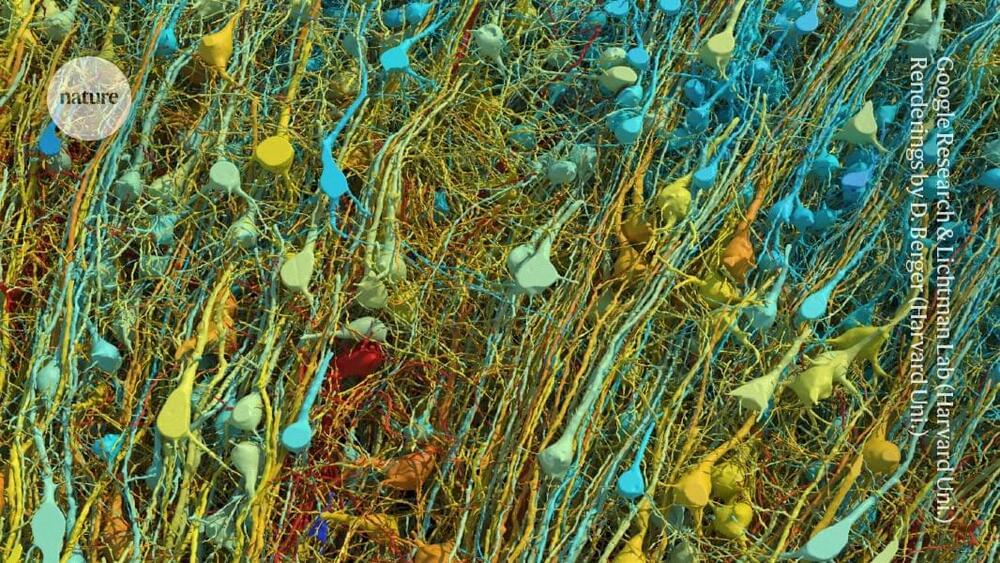

Matthew Lew, associate professor in the Preston M. Green Department of Electrical & Systems Engineering in the McKelvey School of Engineering at Washington University in St. Louis, builds new imaging technologies to unravel the intricate workings of life at the nanoscale. Though they’re incredibly tiny – 1,000 to 100,000 times smaller than a human hair – nanoscale biomolecules like proteins and DNA strands are fundamental to virtually all biological processes.

Scientists rely on ever-advancing microscopy methods to gain insights into these systems work. Traditionally, these methods have relied on simplifying assumptions that overlook some complexities of molecular behavior, which can be wobbly and asymmetric. A new theoretical framework developed by Lew, however, is set to shake up how scientists measure and interpret wobbly molecular motion.