Of the many feats achieved by artificial intelligence (AI), the ability to process images quickly and accurately has had an especially impressive impact on science and technology. Now, researchers in the McKelvey School of Engineering at Washington University in St. Louis have found a way to improve the efficiency and capability of machine vision and AI diagnostics using optical systems instead of traditional digital algorithms.

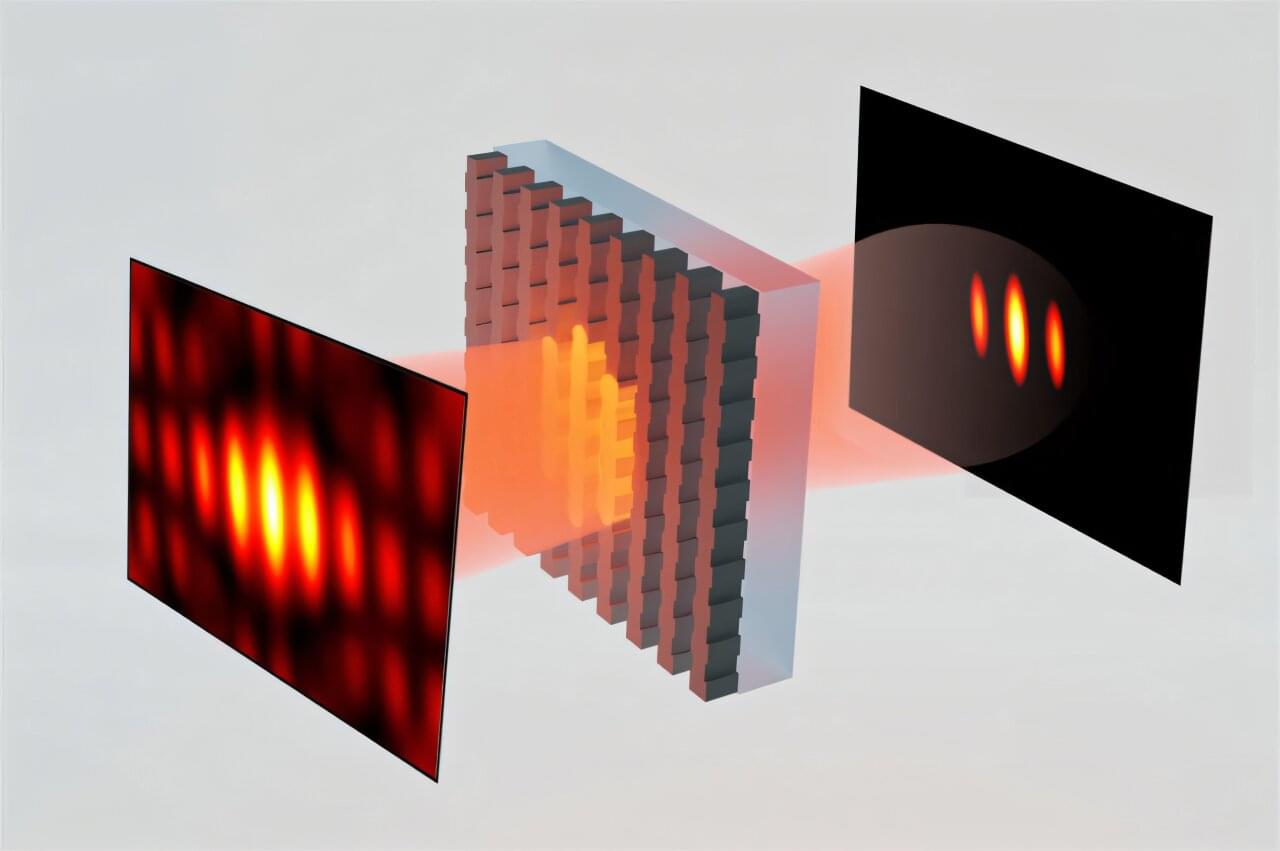

Mark Lawrence, an assistant professor of electrical and systems engineering, and doctoral student Bo Zhao developed this approach to achieve efficient processing performance without high energy consumption. Typically, all-optical image processing is highly constrained by the lack of nonlinearity, which usually requires high light intensities or external power, but the new method uses nanostructured films called metasurfaces to enhance optical nonlinearity passively, making it practical for everyday use.

Their work shows the ability to filter images based on light intensity, potentially making all-optical neural networks more powerful without using additional energy. Results of the research were published online in Nano Letters on Jan. 21, 2026.