A study published in Nature Ecology & Evolution reveals a surprising evolutionary insight: sometimes, losing genes rather than gaining them can help bacterial pathogens survive and thrive.

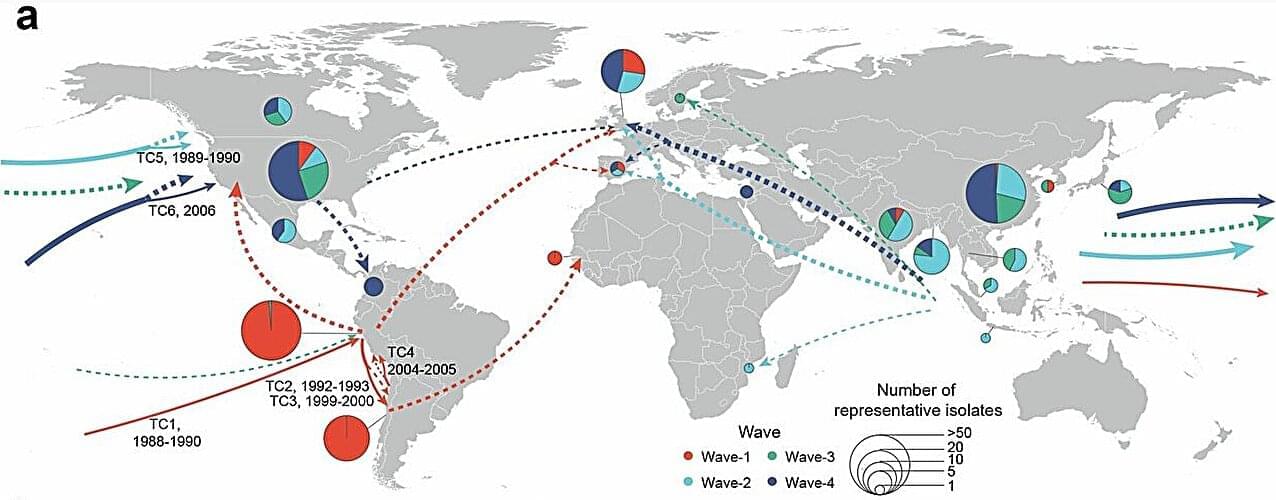

The study was conducted by a group of scientists and coordinated by Jaime Martínez Urtaza, from the Department of Genetics and Microbiology of the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona (UAB); Yang Chao and Falush Daniel, from the Shanghai Institute of Immunity and Infection, Chinese Academy of Science; and Wang Hui, from the Shanghai Jiao Tong University.

When we think of evolution, we often imagine organisms changing or gaining new genes to adapt, such as growing wings, developing resistance, or evolving new behaviors. Across the tree of life, both spontaneous mutations and gene acquisition are classic tools of adaptation. However, in this study, researchers went down a lesser known and scarcely explored evolutionary path, the one of gene loss.