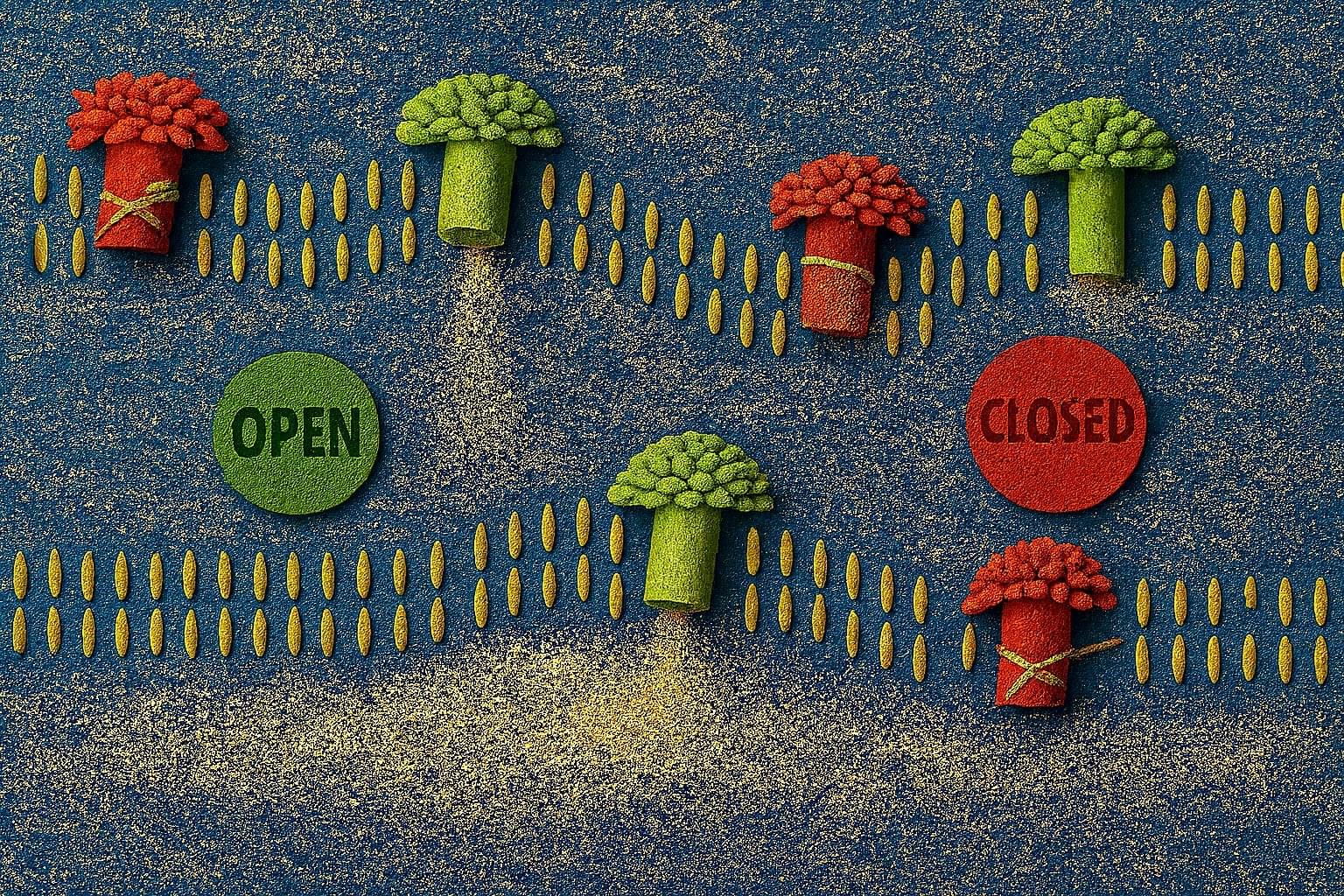

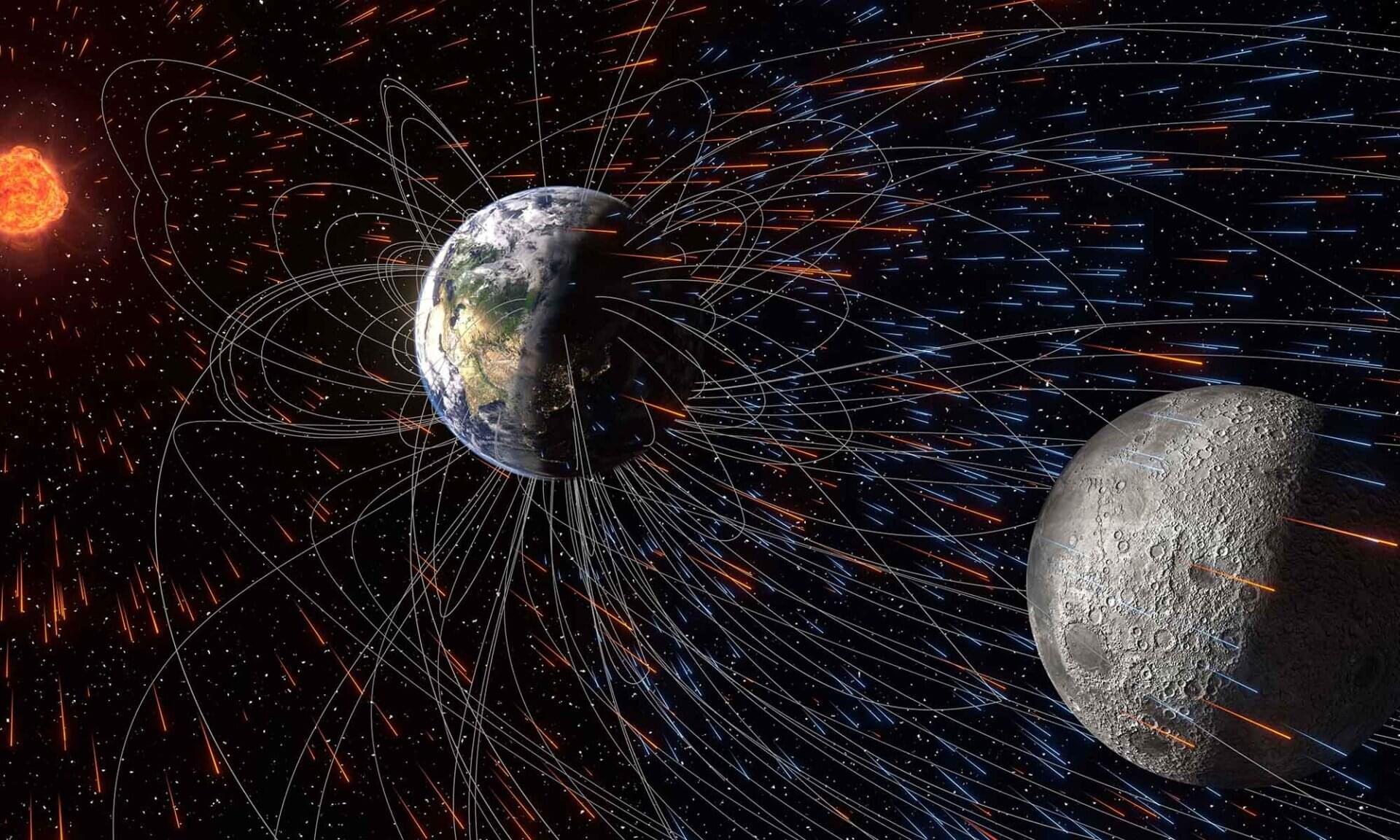

Quantum computers will need large numbers of qubits to tackle challenging problems in physics, chemistry, and beyond. Unlike classical bits, qubits can exist in two states at once—a phenomenon called superposition. This quirk of quantum physics gives quantum computers the potential to perform certain complex calculations better than their classical counterparts, but it also means the qubits are fragile. To compensate, researchers are building quantum computers with extra, redundant qubits to correct any errors. That is why robust quantum computers will require hundreds of thousands of qubits.

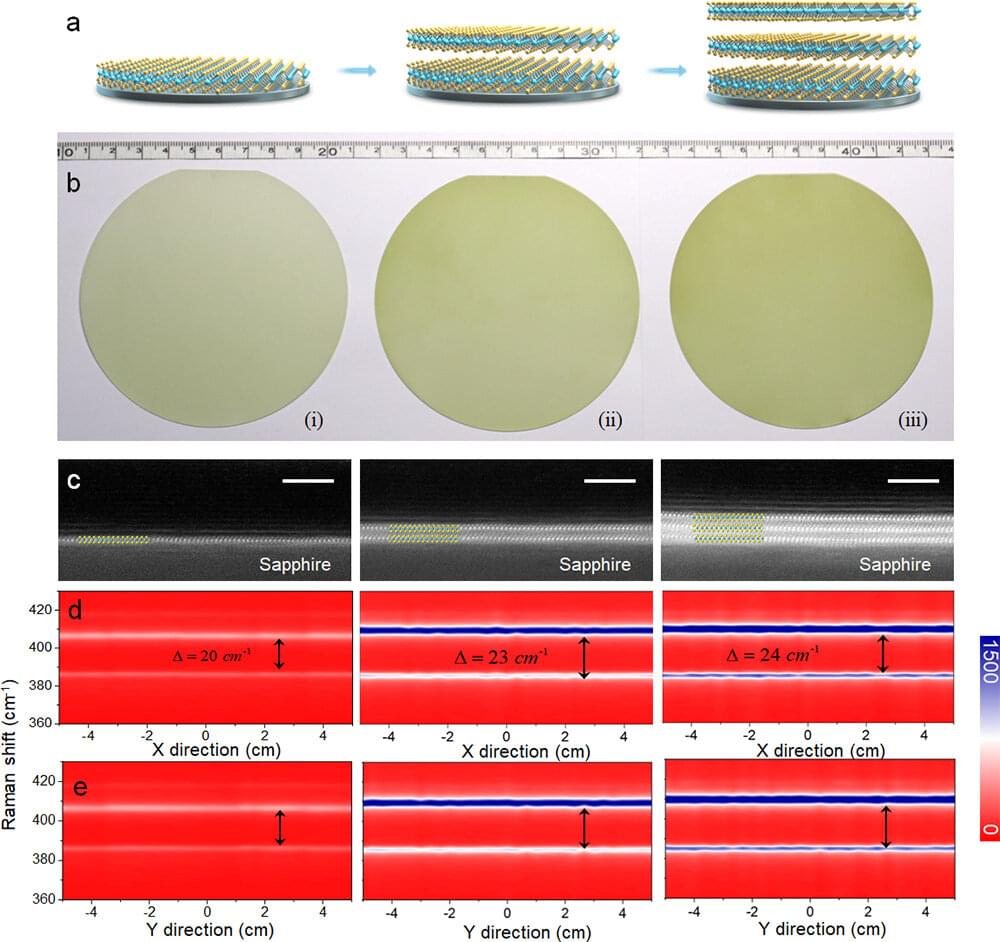

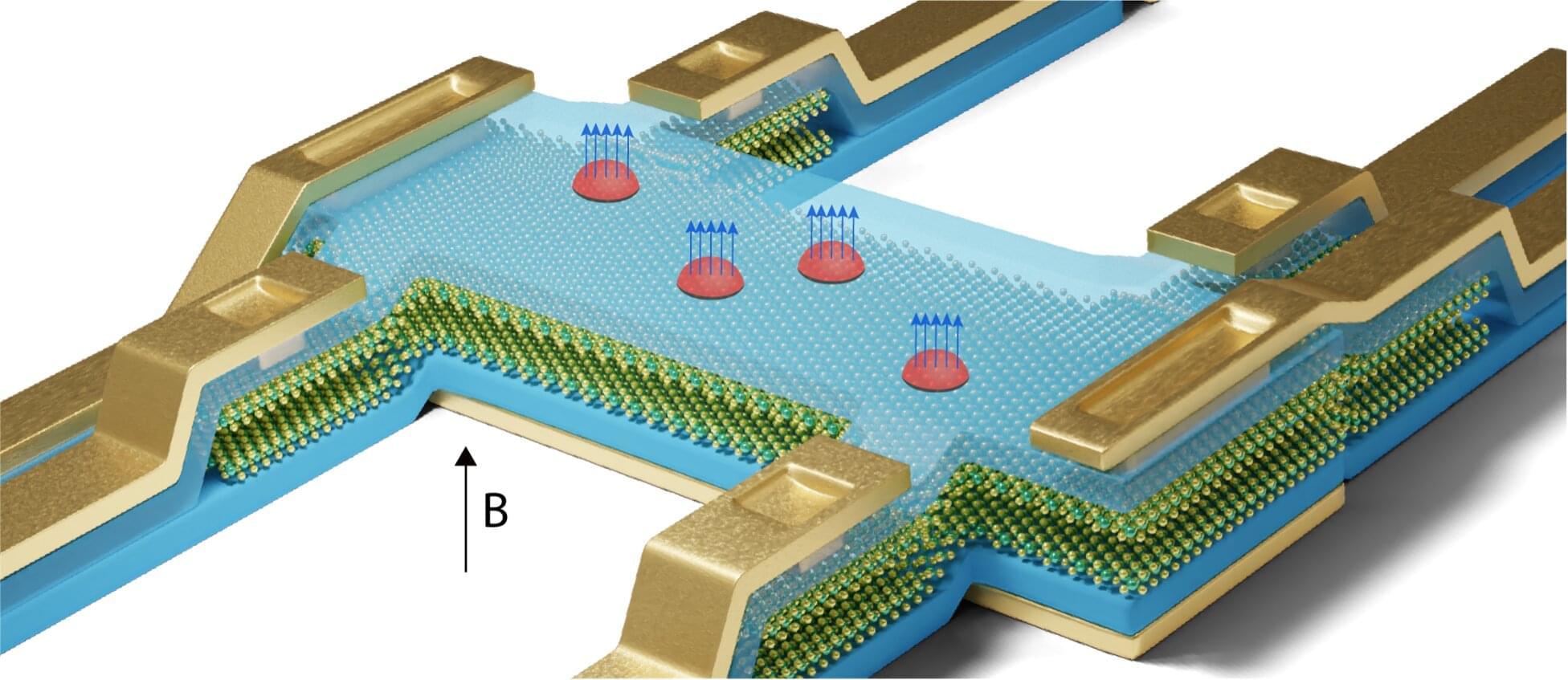

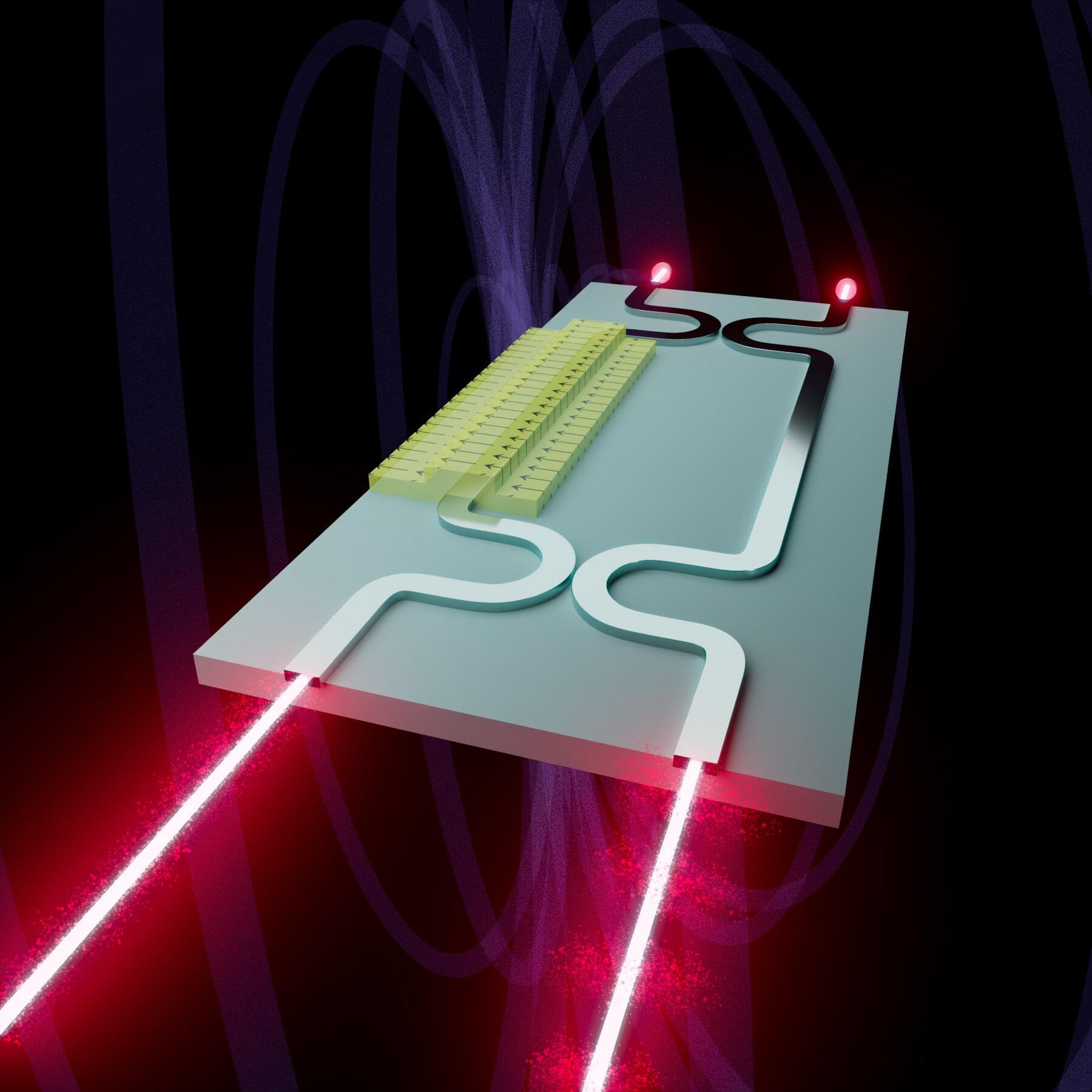

Now, in a step toward this vision, Caltech physicists have created the largest qubit array ever assembled: 6,100 neutral-atom qubits trapped in a grid by lasers. Previous arrays of this kind contained only hundreds of qubits.

This milestone comes amid a rapidly growing race to scale up quantum computers. There are several approaches in development, including those based on superconducting circuits, trapped ions, and neutral atoms, as used in the new study.

The neutral-atom platform shows promise for scaling up quantum computers.