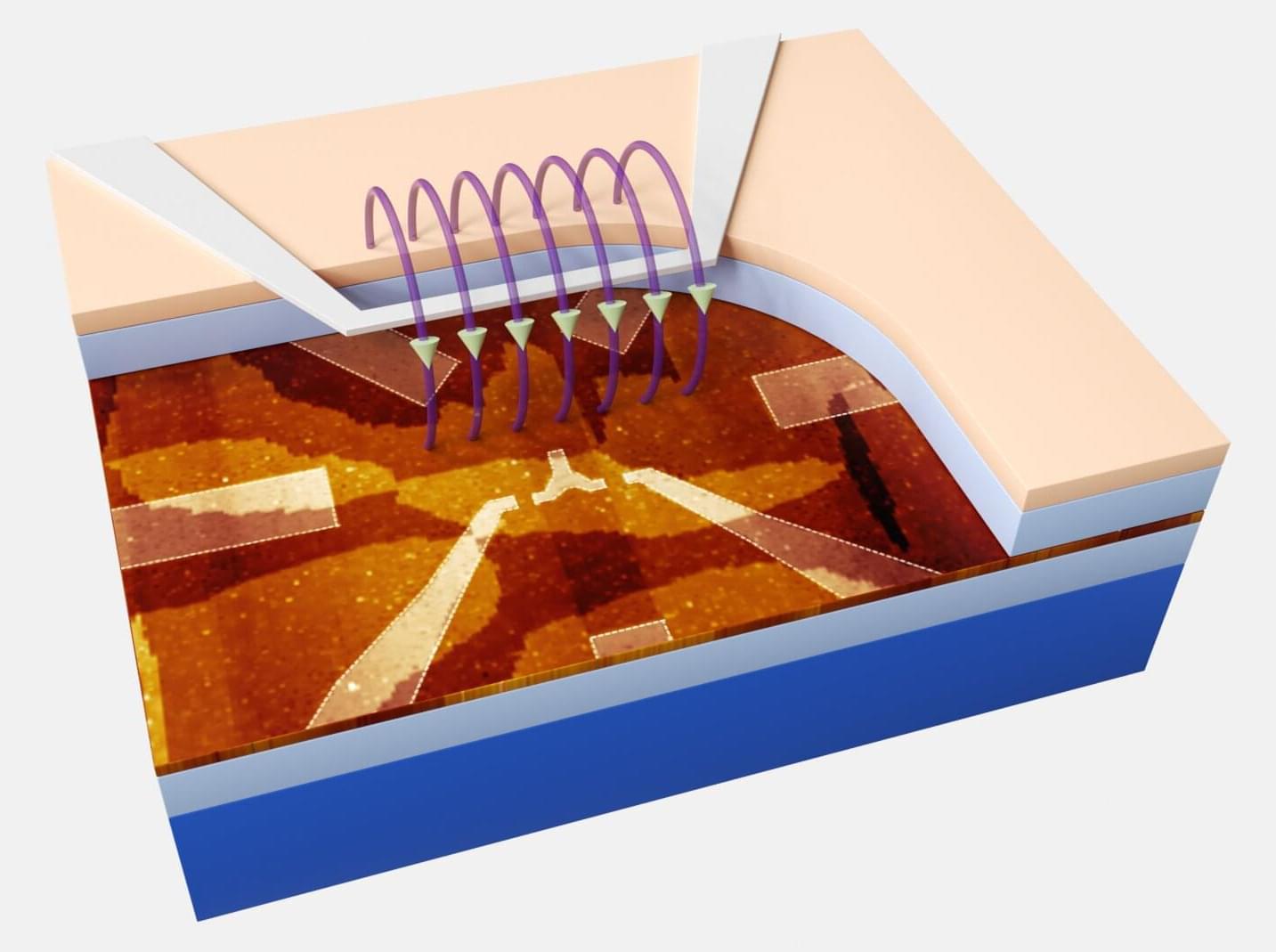

In the race for lighter, safer and more efficient electronics—from electric vehicles to transcontinental energy grids—one component literally holds the power: the polymer capacitor. Seen in such applications as medical defibrillators, polymer capacitors are responsible for quick bursts of energy and stabilizing power rather than holding large amounts of energy, as opposed to the slower, steadier energy of a battery.

However, current state-of-the-art polymer capacitors cannot survive beyond 212 degrees Fahrenheit (F), which the air around a typical car engine can hit during summer months and an overworked data center can surpass on any given day.

In Nature, a team led by Penn State researchers reported a novel material made of cheap, commercially available plastics that can handle four times the energy of a typical capacitor at temperatures up to 482 F.