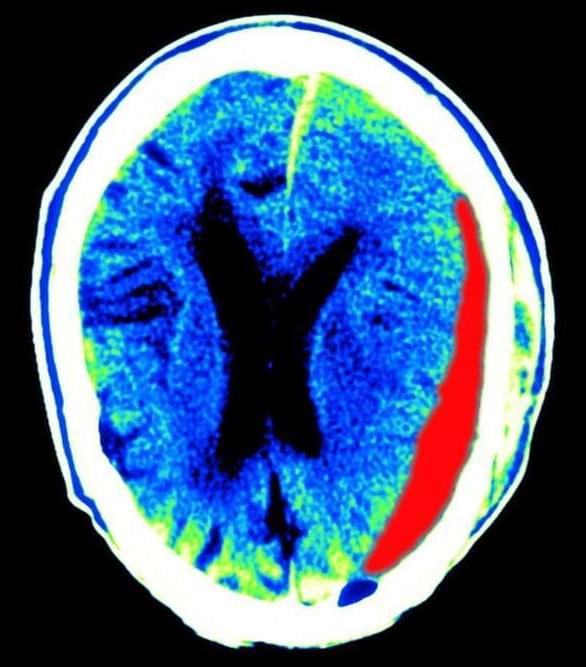

Blood test detects stroke quickly:

The Testing for Identification of Markers of Stroke trial shows the accuracy of a new blood test for identifying stroke.

A team of scientists has developed a new test by combining blood-based biomarkers with a clinical score. The main goal was to identify patients experiencing large vessel occlusion (LVO) stroke.

LVO strokes, a severe form of stroke, are often characterized by a sudden onset of symptoms and significant neurological damage. They occur when an artery in the brain is blocked, depriving the brain of essential oxygen.