The same cell therapy could potentially be used to treat multiple solid tumors like ovarian, pancreatic and lung cancers.

Although they’re constantly improving, robots aren’t necessarily known for their gentle touch. A new robotic system from MIT and Stanford takes a unique stab at changing that, with a robot that uses vine-like tendrils to do its lifting.

The system the engineers developed consists of a series of pneumatic tubes that deploy from a pressurized box on one side of a robotic arm, use air pressure to snake under or around a specific object, then rejoin the arm on the other side where they are clamped in place. Once clamped, the arm itself can move, or the tube can be wound up to lift or rotate the object in its grasp. The ability to deploy the tubes and then recapture them is the real breakthrough here, improving on previous vine-based robots by allowing the system to close its own loops.

“People might assume that in order to grab something, you just reach out and grab it,” says study co-author Kentaro Barhydt, from MIT’s Department of Mechanical Engineering. “But there are different stages, such as positioning and holding. By transforming between open and closed loops, we can achieve new levels of performance by leveraging the advantages of both forms for their respective stages.”

Researchers at Örebro University have developed two new AI models that can analyse the brain’s electrical activity and accurately distinguish between healthy individuals and patients with dementia, including Alzheimer’s disease.

“Early diagnosis is crucial in order to be able to take proactive measures that slow down the progression of the disease and improve the patient’s quality of life,” says Muhammad Hanif, researcher in informatics at Örebro University.

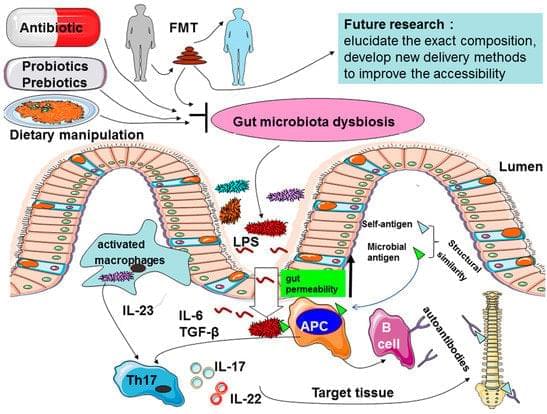

Ankylosing spondylitis (AS) is a chronic inflammatory disease primarily affecting the sacroiliac joints and the spine, for which the pathogenesis is thought to be a result of the combination of host genetic factors and environmental triggers. However, the precise factors that determine one’s susceptibility to AS remain to be unraveled. With 100 trillion bacteria residing in the mammalian gut having established a symbiotic relation with their host influencing many aspects of host metabolism, physiology, and immunity, a growing body of evidence suggests that intestinal microbiota may play an important role in AS. Several mechanisms have been suggested to explain the potential role of the microbiome in the etiology of AS, such as alterations of intestinal permeability, stimulation of immune responses, and molecular mimicry.

In a review of previous studies, McMaster University researchers observe a stronger signal for psilocybin as a treatment for obsessive-compulsive disorder than cannabinoids.

Obsessive-compulsive disorder involves persistent, intrusive thoughts and repetitive mental or physical behaviors, and requires long-term treatment to alleviate symptoms. The ethology of the disorder appears complex, involving multiple biological pathways. Imbalances in central serotonin, dopamine, and glutamate activities are widely thought to play a causative role, placing neurochemistry at the center of many treatment strategies.

First-line treatment includes selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and cognitive behavioral therapy using exposure and response prevention. Roughly 40–60% of patients remain unresponsive to psychotherapy or pharmacotherapy, alone or combined, placing many people in the category of treatment-resistant OCD.

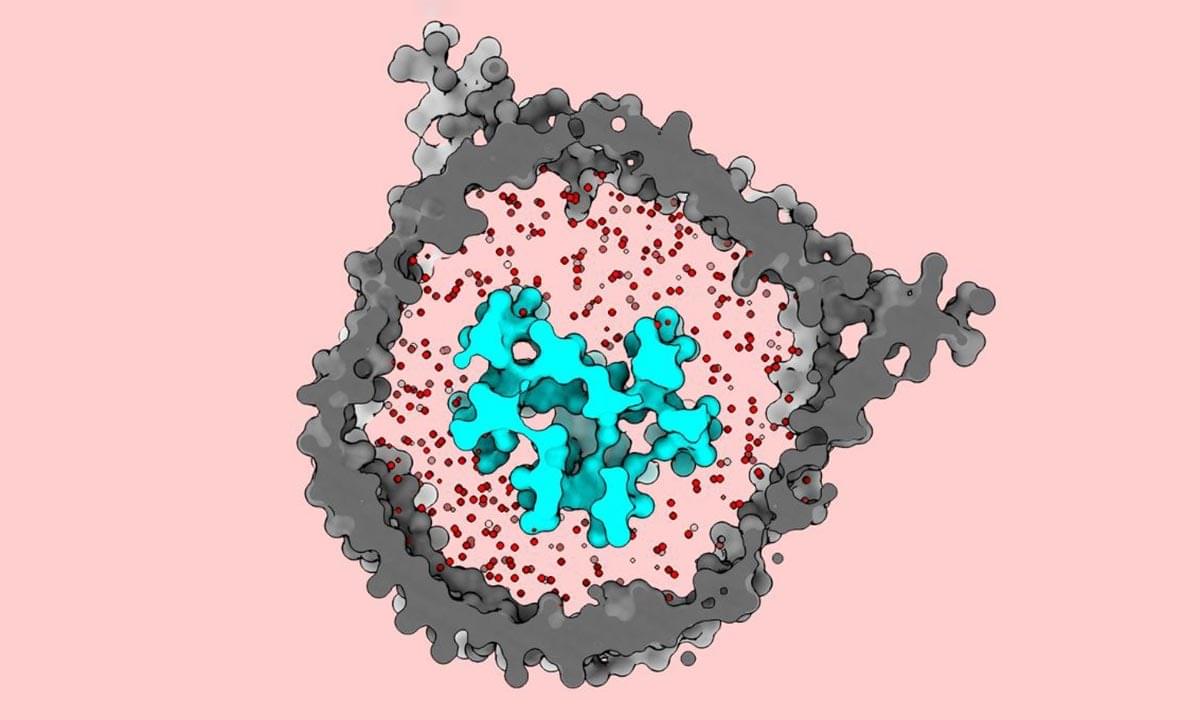

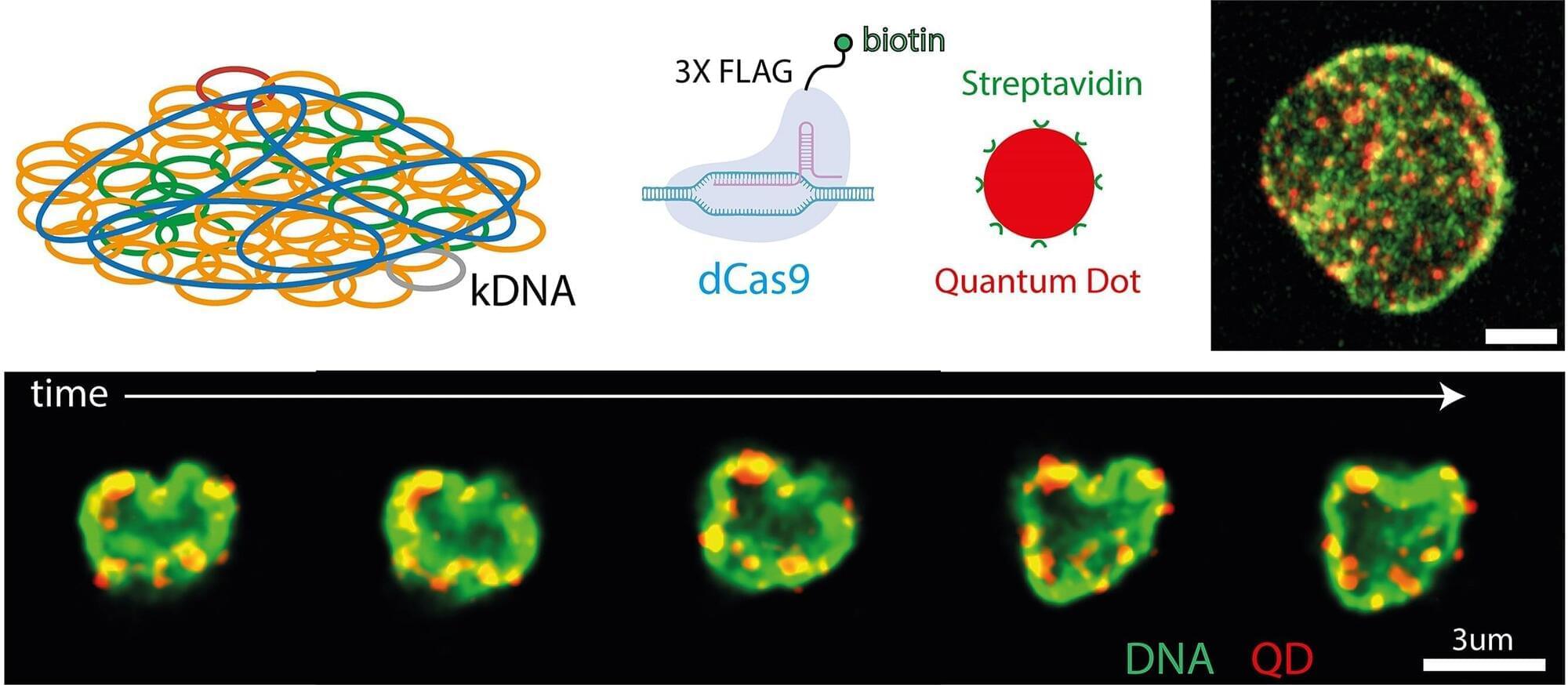

As tough as medieval chainmail armor and as soft as a contact lens. This material is not taken from science fiction, it is a natural structure made of thousands of DNA circles interlinked with each other. Studying it can help us advance our knowledge in many fields, from biophysics and infectious diseases to materials science and biomedical engineering.

This topic is the subject of “Organisation and dynamics of individual DNA segments in topologically complex genomes,” an article that has been published in Nucleic Acid Research.

The study, which also appeared on the front cover of the journal, is the result of a collaboration between the Department of Physics of the University of Trento, with Guglielmo Grillo under the supervision of Luca Tubiana, and the Department of Physics and Astronomy of the University of Edinburgh, with Saminathan Ramakrishnan and Auro Varat Patnaik, supervised by Davide Michieletto.

Scientists have used a specially engineered virus to help track the brain changes caused by psilocybin in mice, revealing how the drug could be breaking loops of depressive thinking.

This may explain why psilocybin keeps showing positive results for people with depression in clinical trials.

“Rumination is one of the main points for depression, where people have this unhealthy focus, and they keep dwelling on the same negative thoughts,” says Cornell University biomedical engineer Alex Kwan.

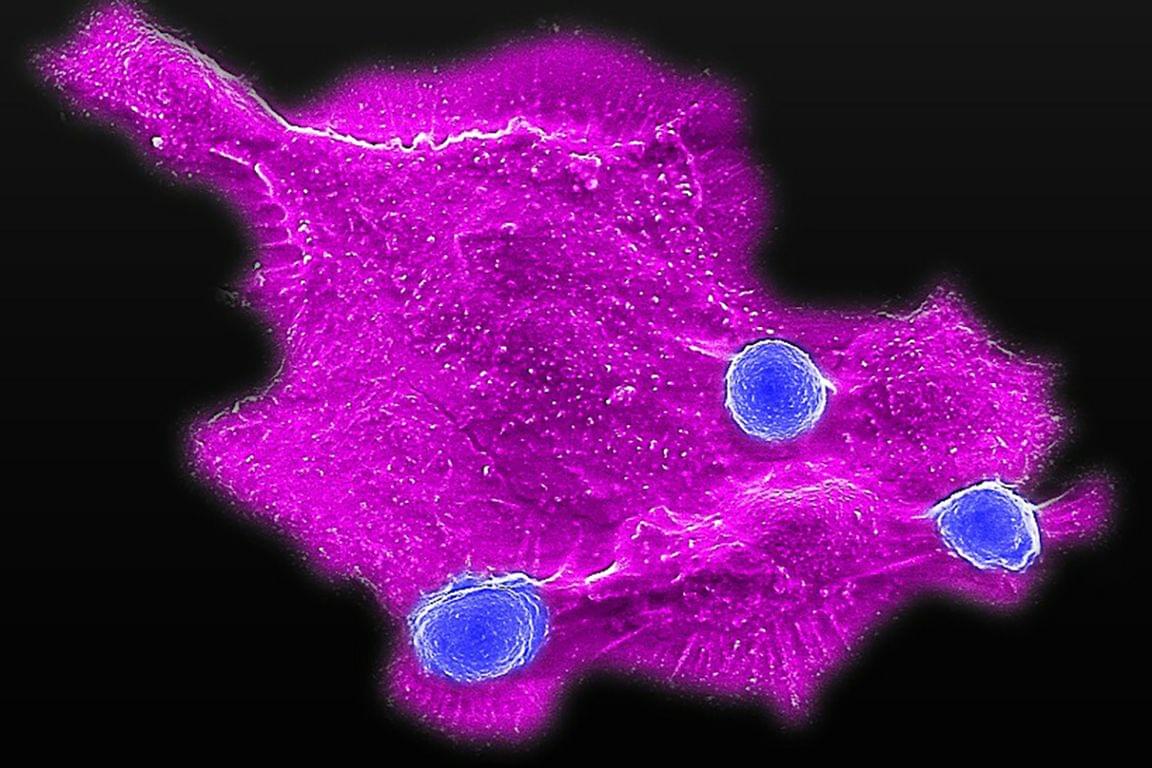

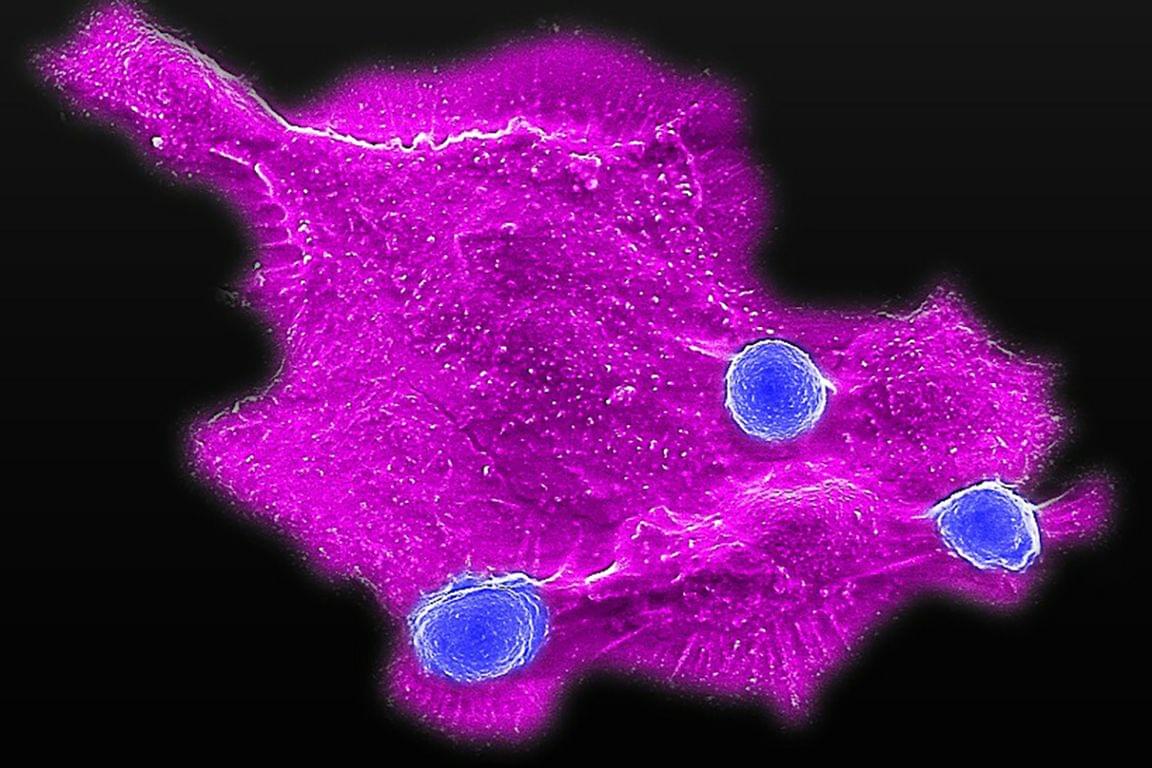

What keeps our cells the right size? Scientists have long puzzled over this fundamental question, since cells that are too large or too small are linked to many diseases. Until now, the genetic basis behind cell size has largely been a mystery. New research has, for the first time, identified a gene in the non-coding genome that can directly control cell size.

In a study published in Nature Communications, a team at The Hospital for Sick Children (SickKids) found that a gene called CISTR-ACT acts as a controller of cell growth. Unlike genes that encode for proteins, CISTR-ACT is a long non-coding RNA (or lncRNA) and is part of the non-coding genome, the largely unexplored part that makes up 98% of our DNA. This research helps show that the non-coding genome, often dismissed as “junk DNA,” plays an important role in how cells function.

“Our study shows that long non-coding RNAs and the non-coding regions of the genome can drive important biological processes, including cell size regulation. By carefully examining a wide range of cell types and phenotypes, we identified the first causal long non-coding RNA that directly influences cell size,” says Dr. Philipp Maass, Senior Scientist in the Genetics & Genome Biology program at SickKids, and Canada Research Chair in Non-Coding Disease Mechanisms.